I first heard people seriously discussing the prospect of “running” a brain in silico back in 2023. Their aim was to emulate, or replicate, all the biological processes of a human brain entirely on a computer.

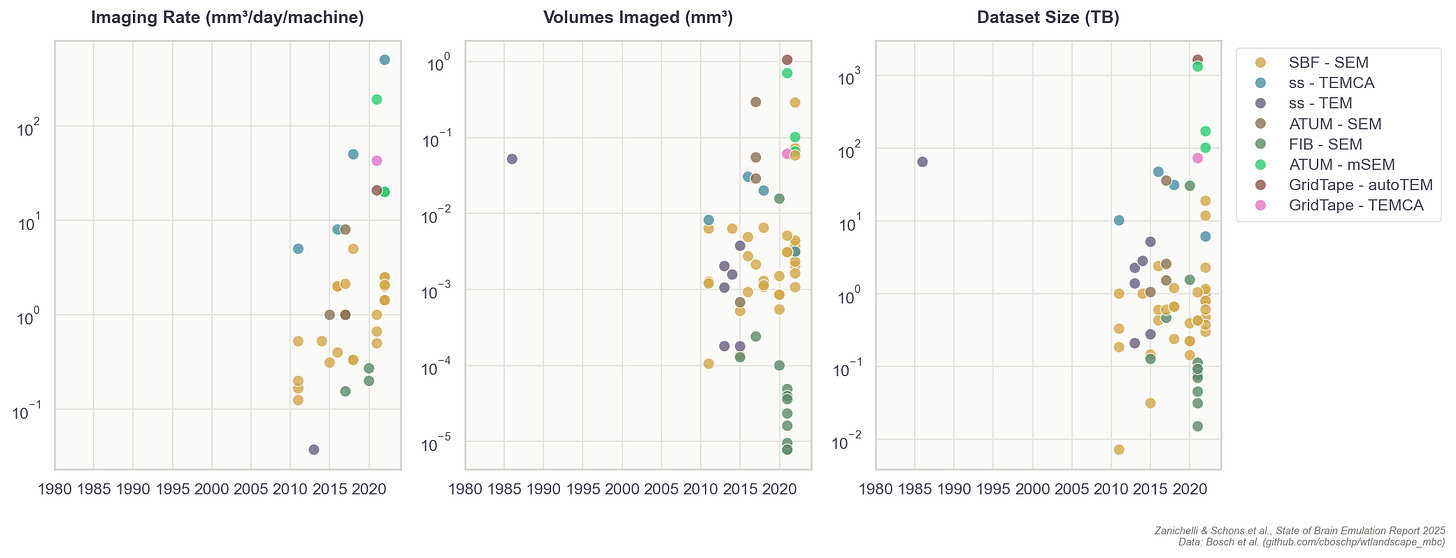

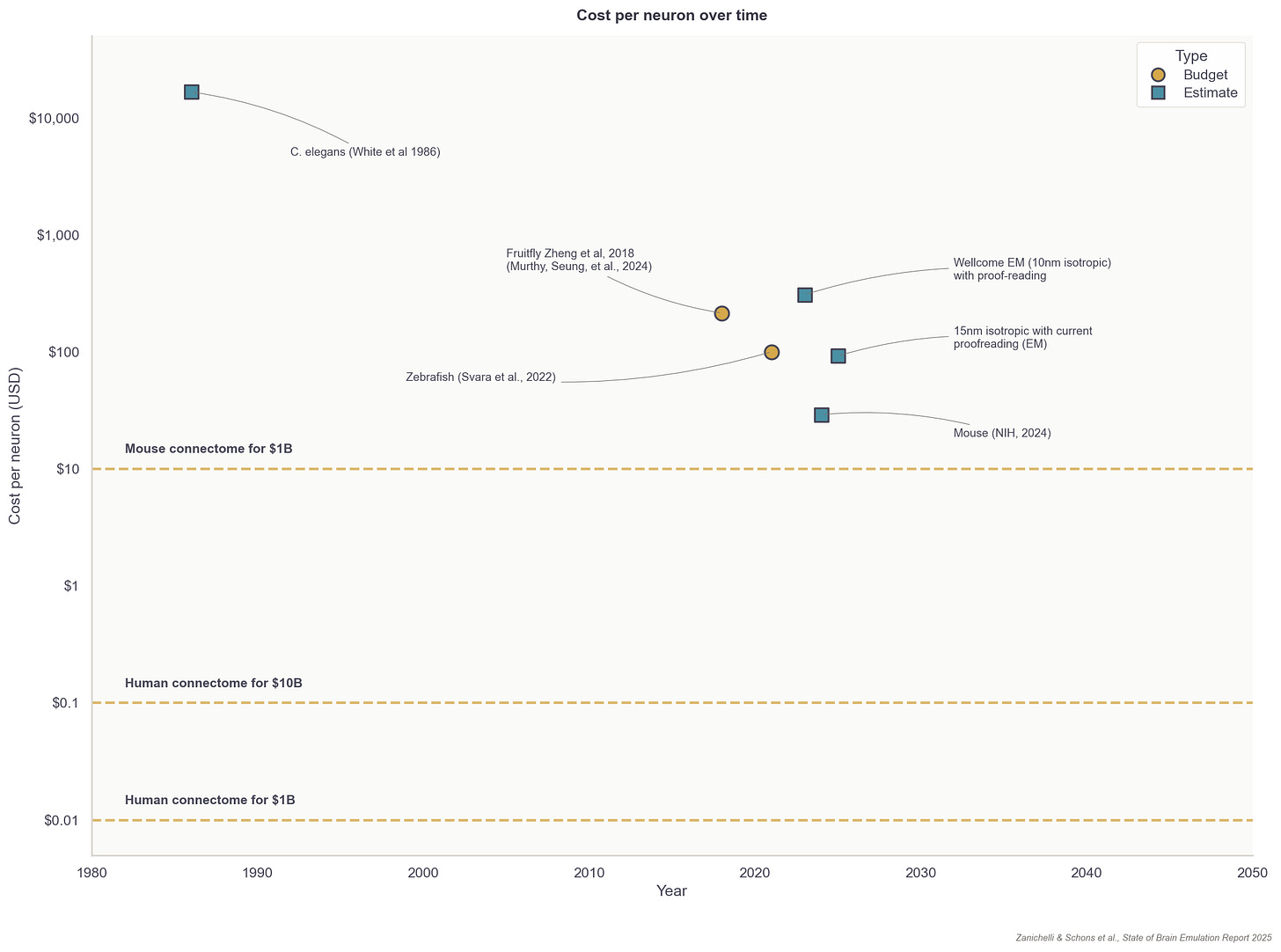

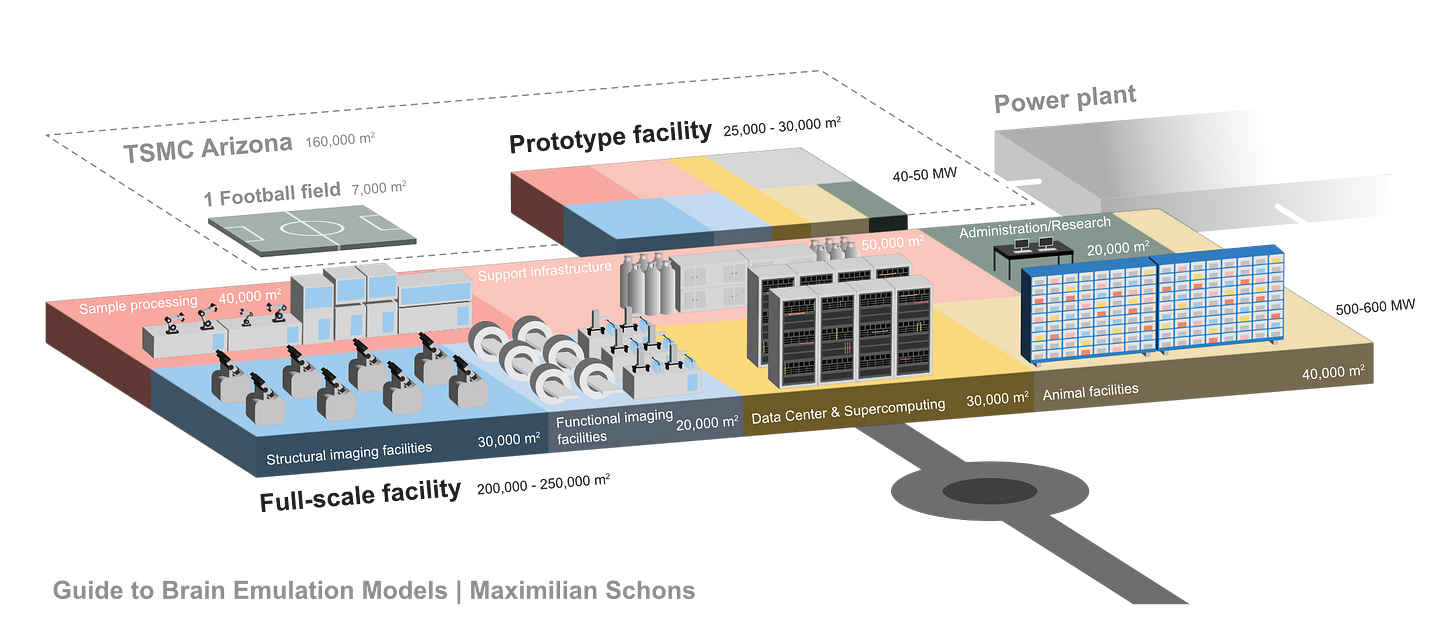

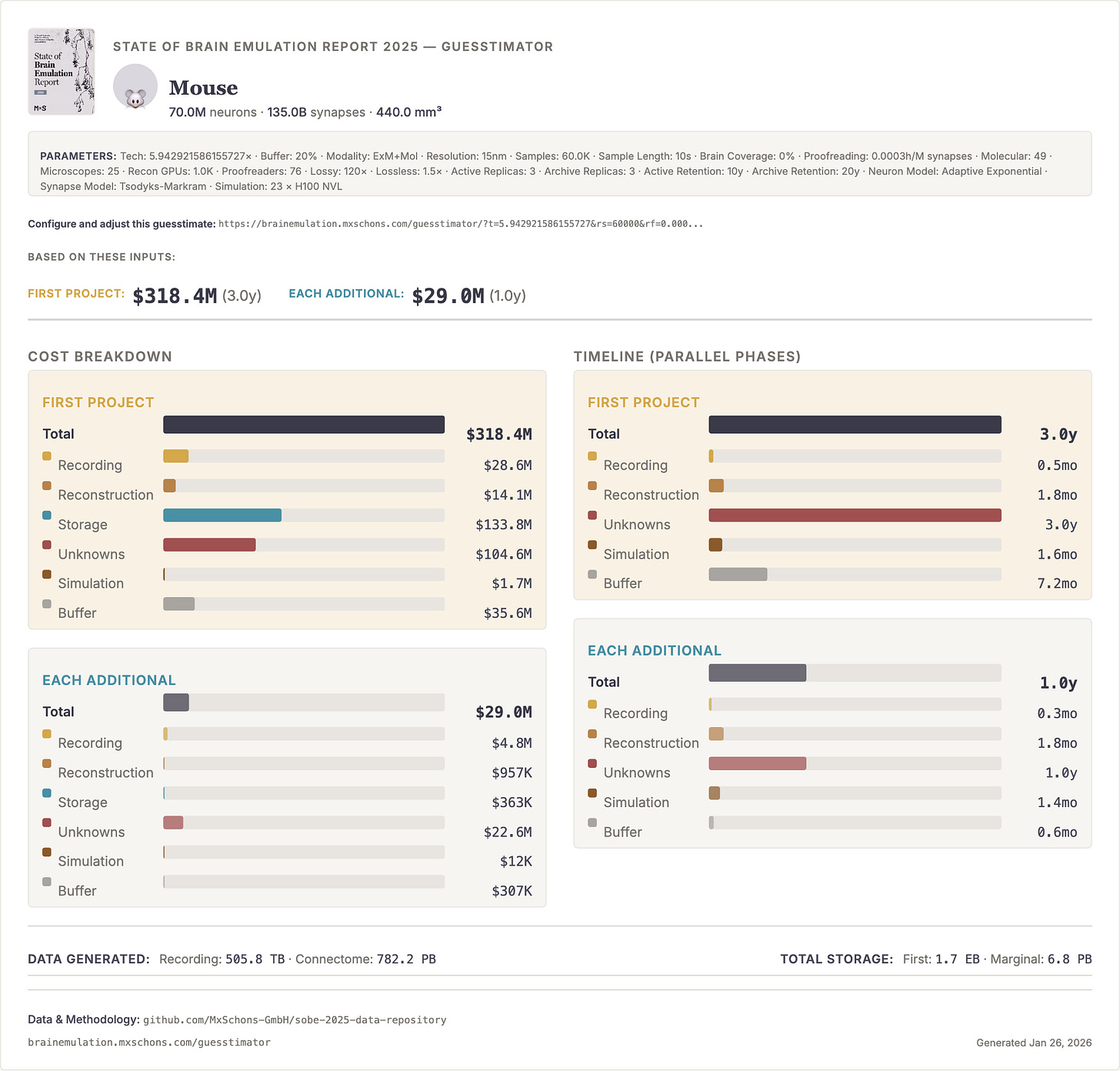

In that same year, the Wellcome Trust released a report on what it would take to map the mouse connectome: all 70 million neurons. They estimated that imaging would cost $200-300 million and that human proofreading, or ensuring that automated traces between neurons were correct, would cost an additional $7-21 billion. Collecting the images would require 20 electron microscopes running continuously, in parallel, for about five years and occupy about 500 petabytes. The report estimated that mapping the full mouse connectome would take up to 17 years of work.

Given this projection — not to mention the added complexity of scaling this to human brains — I remember finding the idea of brain emulation absurd. Without a map of how neurons in the brain connect with each other, any effort to emulate a brain computationally would prove impossible. But after spending the past year researching the possibility (and writing a 175-page report about it), I’ve updated my views.

Three recent breakthroughs have provided a path toward mapping the full mouse brain in about five years for $100 million. First, thanks to advances in expansion microscopy, we can now “enlarge” the brain to twenty times its normal size using a swellable polymer. This makes it far simpler to image neurons and trace their connections using light rather than electron microscopes. Second, E11 Bio (a nonprofit research organization) recently developed protein barcodes, stained with colorful antibodies that, when delivered into brain tissue, cause each neuron to light up in a distinct color. This makes tracing them much easier. And third, Google Research released PATHFINDER last May, an AI-based, neuron-tracing tool that can proofread about 67,200 cubic microns of brain tissue per hour, with very high accuracy.

These technical advances are just one part of the “brain emulation pipeline,” and scaling these methods to human brains may still prove a challenge. But given these breakthroughs and other trendlines, I now find it plausible that readers of this essay will live to see the first human brain running on a computer; not in the next few years, but likely in the next few decades. This computational brain emulation won’t just be an abstract mathematical reconstruction, either, but rather an accurate, digital brain architecture represented in a virtual body that behaves indistinguishably from our own flesh-and-blood brains.

Such an achievement would have enormous real-world value. When I began researching brain emulation, my motives were primarily centered around constraining risks and harms from advanced AI. I thought that, if only we could directly impart thought and behavior from our brains into AI models, then perhaps they would act in greater alignment with our own values. Today, I am less certain about this assumption, given the velocity of AI development. But there are many other (potentially even greater) value propositions for brain emulations.

Many drugs, materials, and methods, for example, are created by identifying and borrowing ingenuity from nature. Scientific discovery tools, from pipettes to chromatography, were necessary to enable this process. I think of brain emulation models as the scientific discovery tool for studying the computational solutions nature has arrived at, so that we might deploy them elsewhere. Accurate brain emulation models also suggest that one could run at least some experiments digitally before performing them in vivo, saving valuable resources in contexts such as mental health research. And, most importantly, as we don’t yet understand the relationship between the firing of neurons, personality, and consciousness, perhaps brain models could help draw these links and rapidly test hypotheses. By building brains in silico, we will come to understand neuroscience. (Or, to quote Richard Feynman, “What I cannot create, I do not understand.”)

Of course, there are other ways of studying disease and consciousness that don’t involve replicating a complete brain on a computer. But the unique advantage of brain emulation models, I’d argue, is that they combine the manipulability of computational models with the biological realism of actual neural systems: a sweet spot that neither traditional neuroscience nor pure AI simulation can occupy.

Achieving brain emulation at human-scale during our lifetime is a monumental task. Success depends on both continued technological breakthroughs and a concerted effort to industrialize the whole pipeline of neuroscience. If this work weren’t already technically difficult, it’s also siloed across decentralized academic labs and is only being worked on by a few hundred researchers globally.

This essay is my attempt to describe what it will take to build a computer emulation of a full, human brain. Its details and estimates are distilled from over 3,500 hours of cumulative research with my colleagues, longer documents I’ve written on the subject, and discussions with more than 50 researchers.

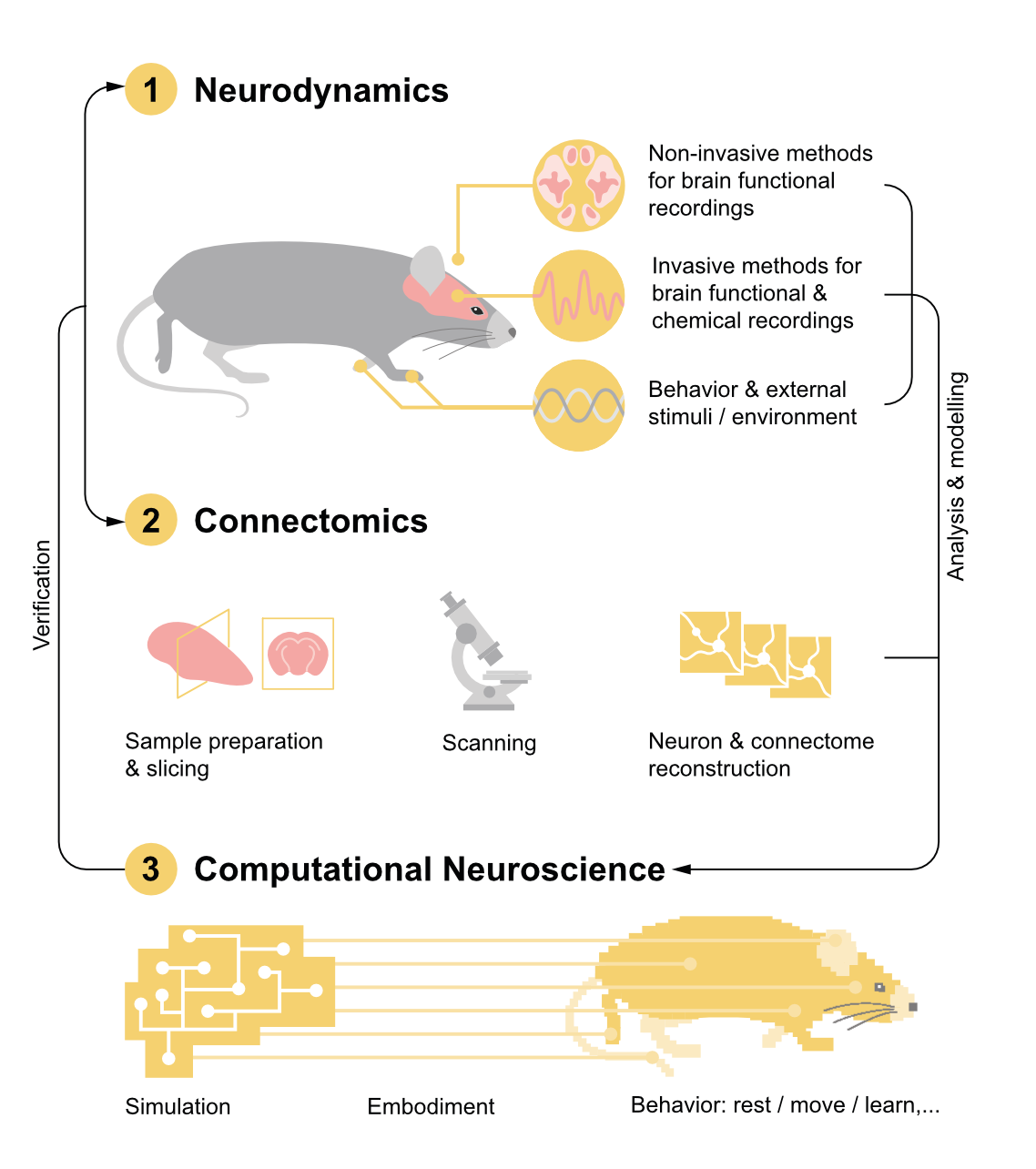

Emulating a human brain will require three core capabilities: first, recording brain activity, second, reconstructing brain wiring, and third, digitally modelling brains with these data. Technology has matured to such an extent that the first brain emulation models for simple organisms like fruit flies or fish larvae could arrive within years. The same technologies could then be scaled to mice and humans, but emulations at that scale will require an enormous investment.

The Current State of Brain Emulation

Emulators are not the same as simulators.

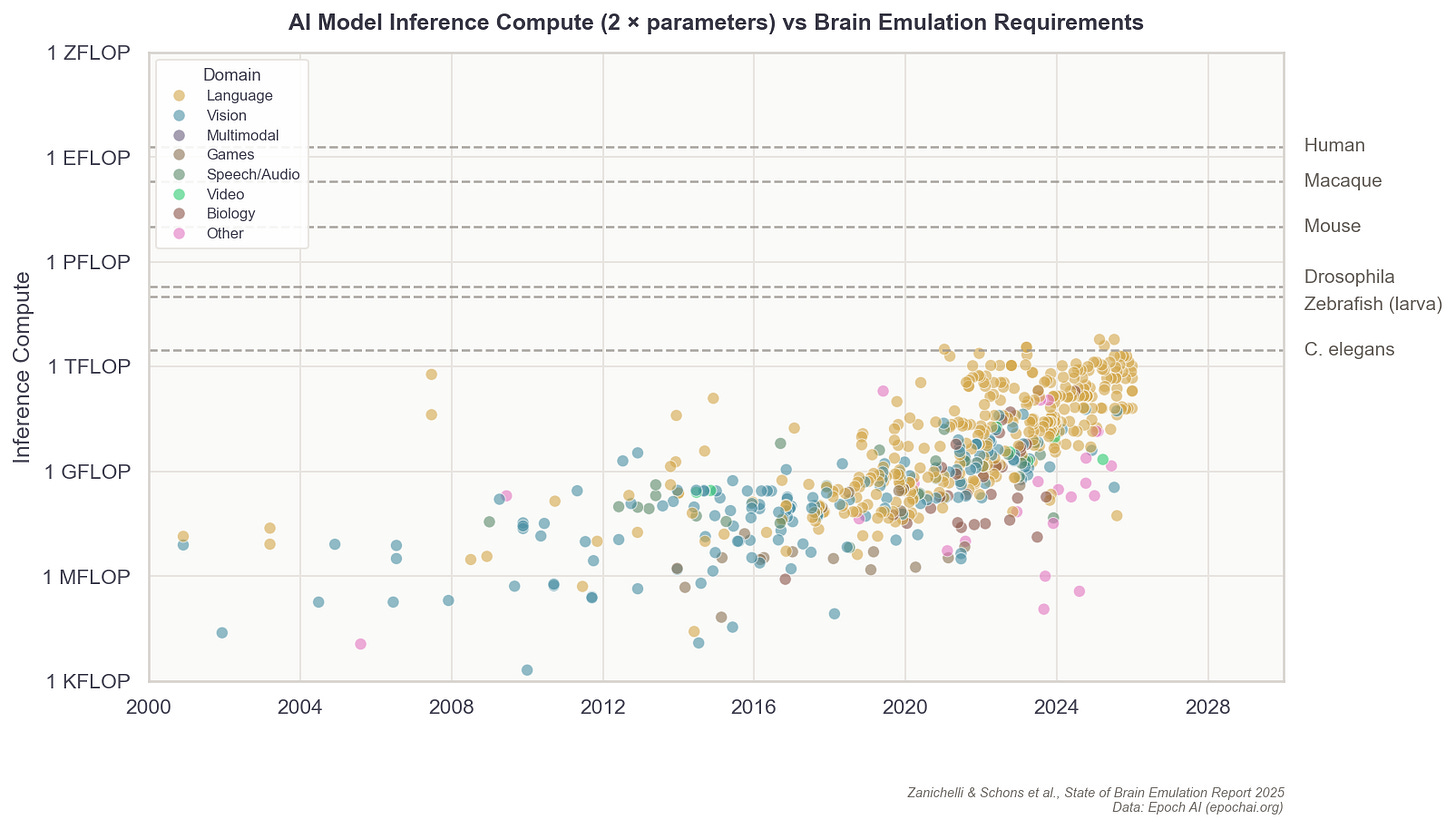

Modern large language models can finish a sentence as a human would (and, increasingly, replicate other aspects of human behavior and affect, such as voices). Even so, these models are not brain simulators because they use different architectures from those used by the human brain as it processes information.1 This is similar to how airplanes achieve flight using jet engines and a metal frame, rather than by replicating the wings, feathers, and muscles of birds.

The brain models made in neuroscience, by contrast, are computer programs that emulate the underlying architecture with as much physical detail as possible. These models seek to instantiate the same neural wiring, firing rates, and overall processing structure of the real, flesh-and-blood neural networks that give rise to behavior.

There is no official list of brain components that must be modeled to create a brain emulation, but I’d argue that any viable one must include: a wiring diagram of the connections between neurons; modeling of certain non-neuron cell types and modulatory systems like hormones; accurate modeling of neural activity based on those factors; and changes in the neural wiring due to activity, also called neuroplasticity.

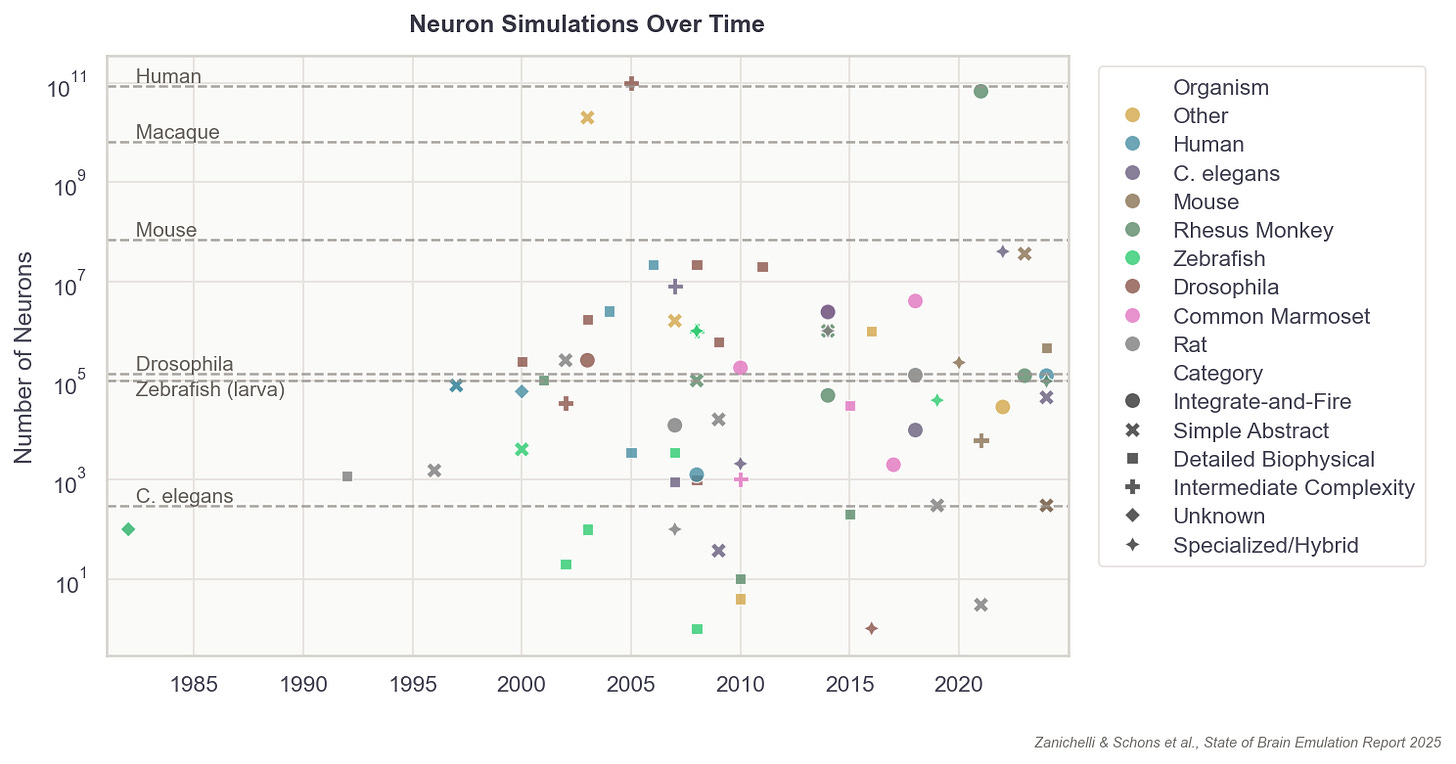

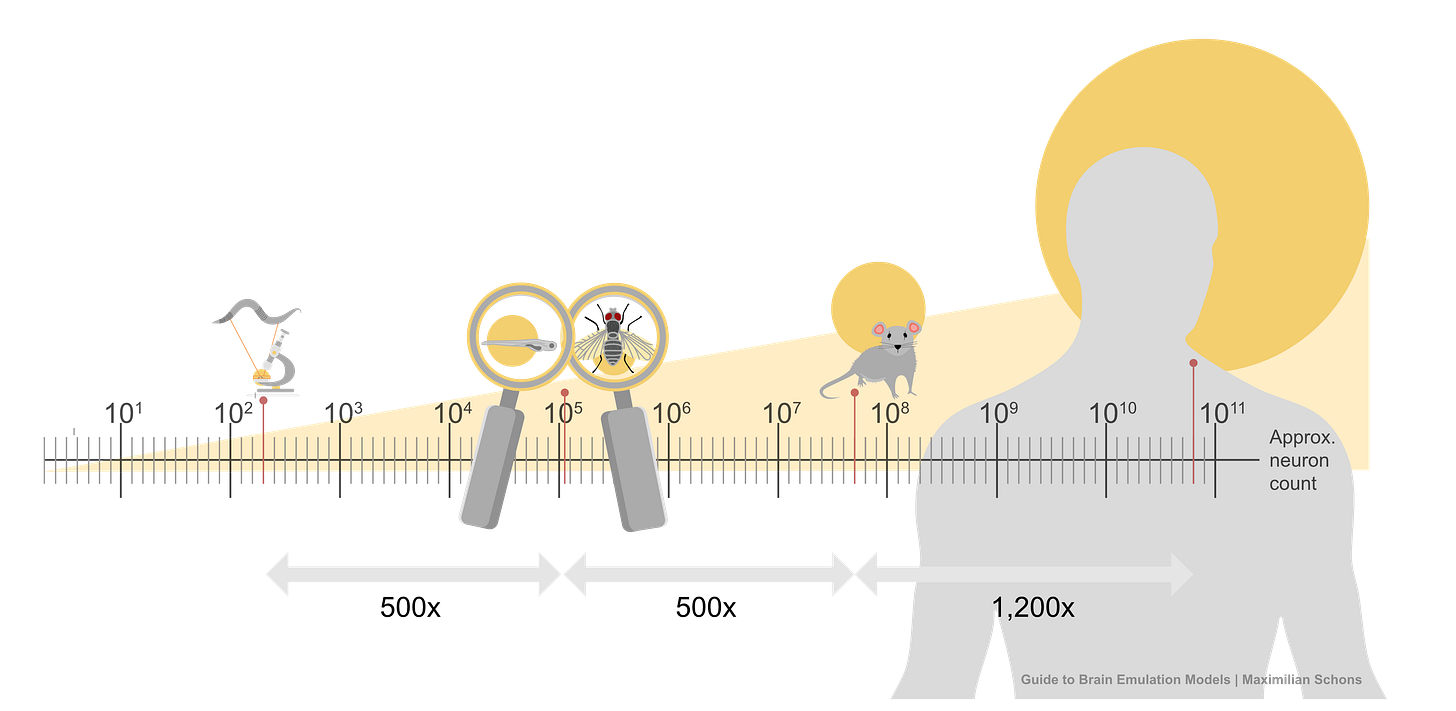

This list of components doesn’t seem intractable, yet no extant brain emulation model contains all of them. And this shortcoming is not for lack of trying. Scientists have developed basic brain models encompassing all the neurons in worms, larval zebrafish, and fruit flies. For mice, whose brains have approximately 70 million neurons (~500x more than fruit flies), we have only models of brain regions, such as 50 thousand neurons of a column in the visual cortex.

Scaling these “small” computational models to an entire human brain is, undoubtedly, computationally demanding. The human brain has about 86 billion neurons. The closest thing to a “true human brain model” created thus far is an effort, from 2024, in which researchers at Fudan University in China simulated all 86 billion neurons using a 14,000-GPU supercomputer. Their model ran at 1/120th speed for about five minutes of biological time.2

Even this most advanced effort is “basic,” however, because the scientists made several complexity-reducing assumptions in order to run the model at all. For example, they made educated guesses about the connectivity between neurons; indeed, the entire simulation’s neuronal wiring diagram was extrapolated based on data from an MRI scan of the author’s own brain, collected at a resolution one million times coarser than the width of a single cell. Even with access to a supercomputer, the researchers also had to downscale the total number of synapses per neuron to an average of 600, roughly five- to ten times less than reality.

To understand why it is so difficult to fully capture the complexity of a brain, consider the fruit fly. Even with their small brains, fruit flies behave in surprisingly complex ways. They walk and fly with rapid maneuvers, groom themselves, and engage in complex courtship rituals involving species-specific songs (yes, fruit flies sing!). They also learn, remember, and even possess idiosyncratic “personalities.”

In 2024, a group at UC Berkeley published a brain model capable of replicating aspects of a fruit fly’s brain as it processed sugar and fed. The model incorporated the exact wiring diagram of all 140,000 neurons in the fruit fly brain, which other scientists had meticulously digitized over a five-year span. To run the model, researchers fed simulated sugar signals into digital taste neurons and let neural activity propagate through the connectome. Each digital neuron computed its firing rate based on its inputs, connection strengths, and whether those connections were excitatory or inhibitory. The resulting activity patterns matched recordings from real flies to a reasonable degree, where firing rates and rhythms were in line with what scientists observe in real flies. And the model successfully emulated a single act of feeding and grooming, which was then validated against real flies’ brain activity.

Although impressive, this model is still far from a complete, virtual fly. Most of the virtual brain was silenced, so as not to interfere with the feeding response, and there was no flying, socializing, learning, or singing.

To revisit the flight metaphor, then, we are currently approaching the stage where we can model a bird’s basic wing flapping, but only under constant wind conditions, without obstacles or transitions into other wing positions — a useful starting point, to be sure, but still massively reductive. Scaling up this work to a full emulation, spanning the entire fruit fly brain, will require drastic improvements in three things: computational neuroscience, neural activity data, and neural wiring data.

Computational neuroscience provides the scaffolding for computers to represent neurons and brains, essentially the software and mathematical equations that describe the rules by which neurons process inputs and generate outputs. These equations include adjustable parameters (how fast a neuron recovers after firing, how strong a given synapse is, etc.), but the values of these parameters need data to be correctly set. That’s where neural activity and wiring data come in.

By recording what neurons actually do in living brains — when they fire, how fast, and in response to what stimuli — scientists can tune those mathematical parameters to match reality. This data must be collected from living organisms, using implanted electrodes that detect electrical signals or optical techniques that make active neurons glow under a microscope.

Finally, neural wiring data reveals whether neurons are connected to each other and, if so, to what degree. Unlike activity recordings, wiring data is obtained from dead tissue: researchers slice brain samples into ultra-thin sections, image each slice with electron microscopes, and then computationally reconstruct the three-dimensional structure of every neuron and synapse.

Building a brain emulation model requires each of these things, at a minimum.

Computational Neuroscience

Brain emulation models are most easily envisioned as large, interconnected networks of much smaller “digital neuron models” that talk to each other. A digital neuron, in turn, is akin to a mathematical formula, describing how a neuron behaves given certain inputs. As these formulas compound to include more and more neurons, the brain emulation model becomes a long, interconnected daisy-chain of functions that feed into each other.

The formula describing a digital neuron could be simple, capturing solely its “on” and “off” patterns, or it could capture everything from their ion channels to their membrane properties. In general, the more parameters these formulas contain, the more expressive they can be in recapitulating a neuron’s firing speeds, delays, recovery periods, and synapses. Even a single digital neuron with a few synapses has at least hundreds of parameters. In more detailed models, there are often millions. A complete brain emulation model consists of hundreds of thousands to billions, quickly driving the total parameter count for larger brains to levels that dwarf even today’s largest AI models.3

Each parameter also has its own storage and compute needs. Even with fairly simple neuron models, these computational demands accumulate quickly. In practice, an “uncomplicated” neuron with 100 to 10,000 parameters ranges between one to 100 KB in memory and one to ten million operations per second. This is roughly equivalent to the resource demands of dragging along a small 64×64-pixel emoji on a PowerPoint slide with a mouse. And again, this is per neuron. A single computer chip from the 1980s could run about 2,000 such simple, digital neurons.

Scaling this up 150,000 times, to capture all the neurons in a fruit fly, is possible with today’s consumer gaming hardware. But for a human-scale brain model, with its 86 billion neurons, running such a simulation would probably require all the compute contained in a large datacenter.

Although this seems daunting, brain emulation models are not bottlenecked by the computing speed of hardware. Today, the main computational bottleneck is “memory walls;” reading and writing the data quickly enough, rather than doing the computations themselves. Running a mouse brain simulation today, where each neuron is represented as the simplest possible entity, would demand about 20 GPUs. A human simulation would require 20,000 GPUs and still face the aforementioned slowdown issues due to GPUs spending most of their time moving data around.4

Why, then, are there still no “great” computational models of small organisms, like the worm or the fruitfly, if 1980s’ hardware was sufficient to run neuron simulations? The simple answer is that the central challenge of brain emulation is not to store or compute the neurons and parameters, but to acquire the data necessary for setting neuron parameters correctly in the first place.

Adjusting parameters to fit experimental data is called “model fitting.” The individual values in the mathematical equations are adjusted in such a way that the output of digital neurons resembles that of neurons observed in physical wet-lab experiments. For neural connections, the number and type of connections are ideally informed by anatomical scans that resolve neurons down to their smallest structures. But such data is limited due to the complexity and costs of experiments.

This is one of the main reasons why we continue to struggle to accurately replicate even small brains on computers. As with modern large-language models, which had to ingest the whole internet to become useful, brain emulation models will require significantly more biological data, spanning the full breadth of neural behavior, including neural activity and wiring data.

Neural Activity Data

One of the best ways to fit neuron parameters is to measure the precise firing patterns of every single neuron in the brain.5 But, alas, there are currently no methods available to do this at large scales.

Every existing method for scanning the brain must contend with various tradeoffs in resolution, volume of the brain covered, recording duration, sampling rate, and movements of the organism itself. No experiment to date has recorded the single-neuron firing patterns of an adult organism’s entire brain. In fact, the record for such an experiment is a mere 50 percent of neurons in the worm, C. elegans, and only for a few minutes!

Just imagine how difficult it would be to learn anything from a book if you only get a single random page (short duration instead of whole day), only the first part of each sentence on the page (incomplete coverage instead of whole brain), and additionally, some words in those fragments are missing (insufficient sampling rate instead of meeting maximum neuron firing rates). While this is obviously just a metaphor, it captures the current reality for neuroscientists.

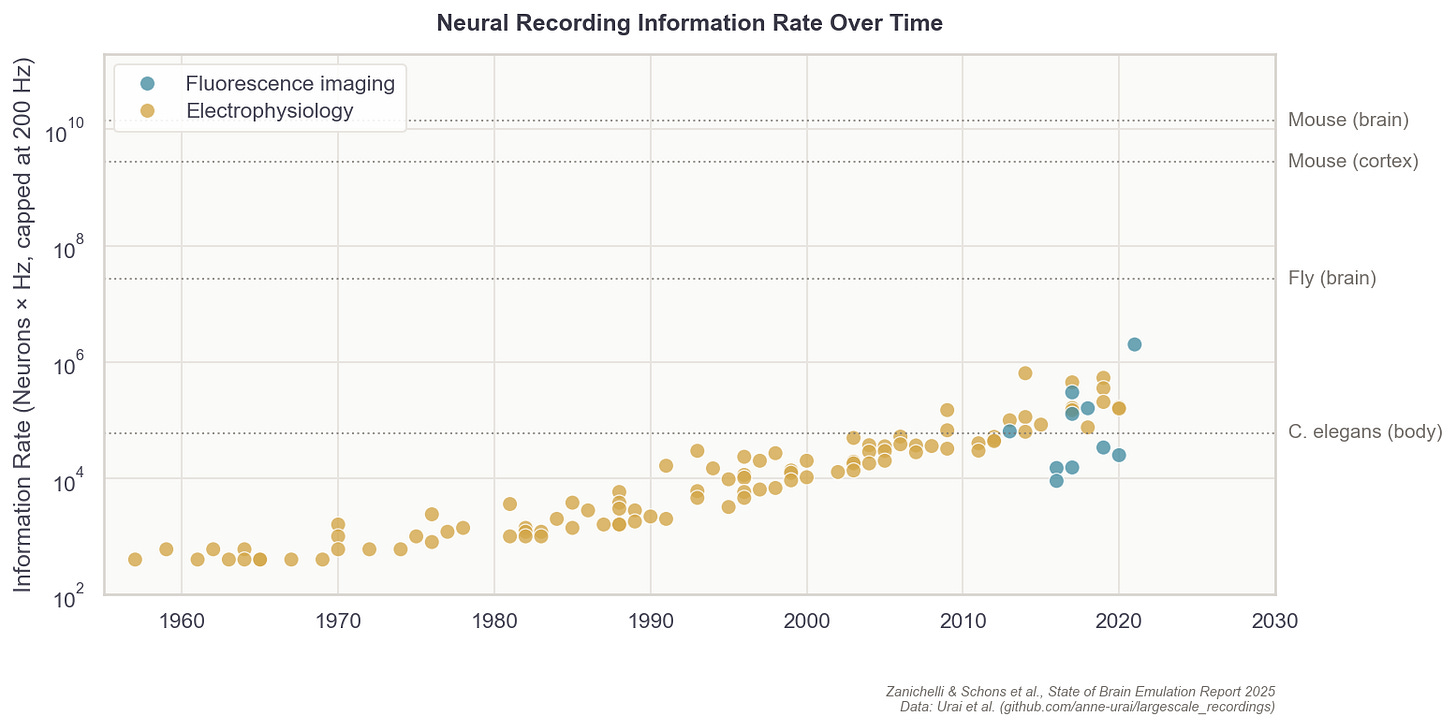

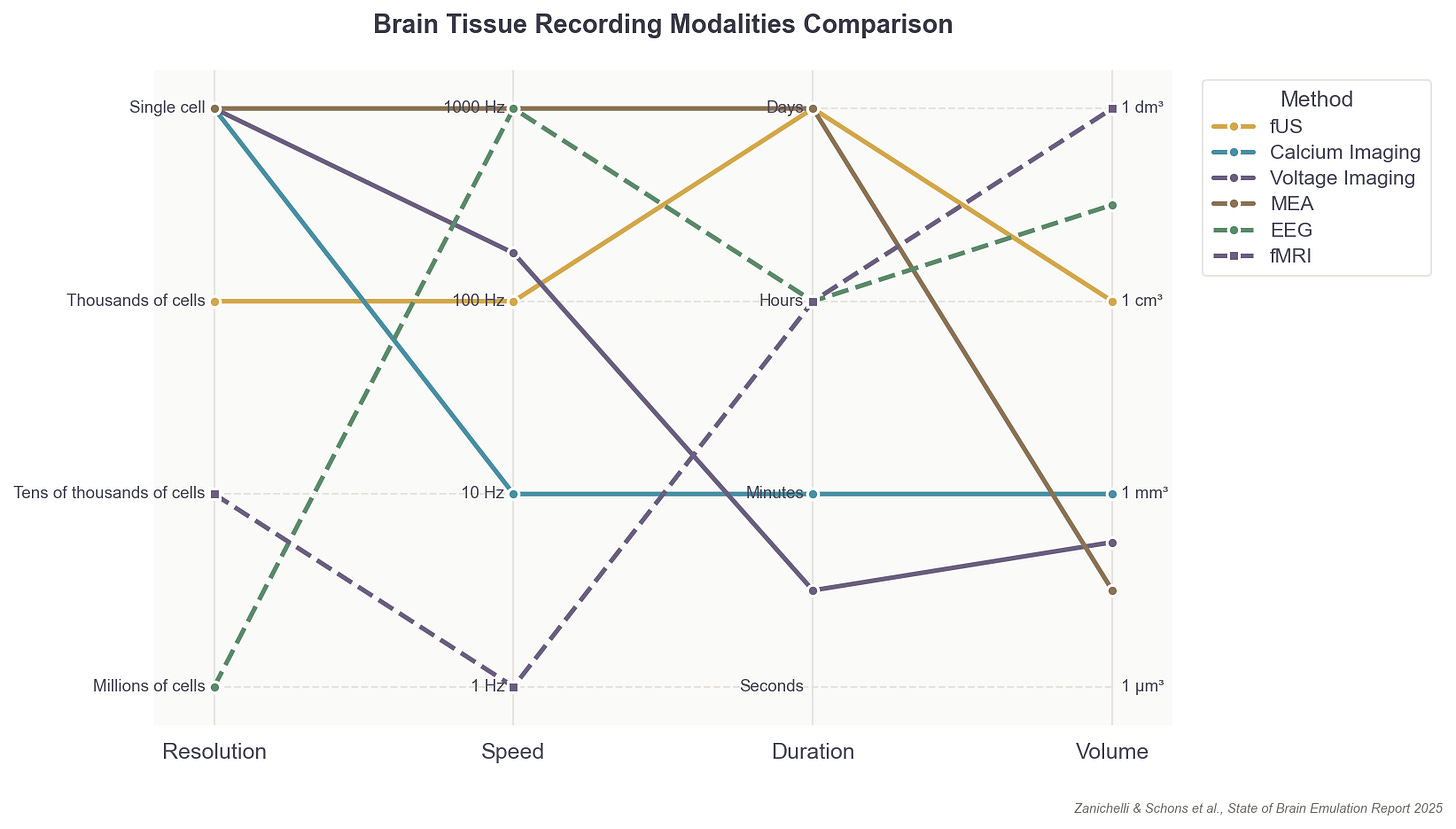

That said, neural recording capabilities are rapidly improving, and two primary recording modalities exist that could capture the activity of individual neurons with sufficient resolution for training accurate models. Both approaches are still quite limited, however, in the number of neurons they can record and in the invasiveness required.

The first is microelectrode arrays, or MEAs, which are small, implanted chips able to record electrical signals directly from tissue: usually up to 1,000 neurons at a time.6 They are akin to dangling many microphones over a conference room to pick up sounds from individual speakers. MEAs, though, don’t easily scale across large brain volumes, as the needle threads containing each electrode must penetrate (and thus damage) brain tissue. With MEAs, it’s also difficult to figure out which neurons produced which signal.

The second option is to employ optical microscopy to watch neural activity directly. For example, scientists can genetically engineer neurons to express a fluorescent protein, called a calcium sensor, which emits photons when active. Microscopes and lasers are used to “read out” or video record the firing of each neuron containing these sensors.

This approach, like the first, is limited to only small, microscopic segments of the brain; an area a few millimeters wide, or up to one million neurons in total. And much like MEAs, optical single-cell recording can carry surgical risks, as scientists must physically dig into brain tissue to watch the neurons inside. This method can also restrict the natural movements of an organism; in mice, for example, a motion-sensitive microscope must be mounted on their heads.

But still, progress in neural recording technologies has been swift. In the 1980s, electrodes were capable of sampling perhaps five cells in total, about 200 times per second (~ 103 data points per second). Today, with optical imaging, researchers can instead record one million cells about 20 times per second (106). The whole-brain data rate needed for mice, however, would be 14 billion (109), while humans would require 17.2 trillion (1012) per second.7 So while we have increased data rates by 1,000x over the past 40 years, we have far to go before we can accurately sample mammalian brains.

Finally, just because it’s possible to record one million of the 70 million total neurons in mice, or record 1,000 neurons at a rate of 200 times per second in larval zebrafish, does not mean it’s possible to record all 300 neurons in a single C. elegans worm. In fact, the best recordings to date capture about half the neurons in immobilized worms, and less than a third when the worm is allowed to move freely.

The main obstacle is the worm’s motion; while crawling, its 50-micrometer head swings nearly twice its own diameter per second, and the body can twist into sinusoidal, circular, and omega shapes that no current algorithm can follow. I’m making this point in detail because the lack of a working worm brain emulation model is a common objection lobbed about by brain emulation critics, but even the smallest organisms can present data collection difficulties, sometimes greater than those of larger organisms with many more neurons.

Techniques do not easily transfer across species: first, because an organism might lack a genetic toolkit to express fluorescent sensors; second, because they can’t tolerate the fixation required to hold still under a microscope, and third, because their neurons sit too deep for optical imaging to reach. Resolution requirements also differ as fruit fly neurons are much finer than mouse neurons, demanding more precise imaging. In practice, each organism often requires its own methodological breakthroughs.

In contrast to neural activity data, neural wiring data acquisition fortunately has a more generalizable path forward. There, the fundamental pipeline — slicing, imaging, and reconstructing — generally works well across species. The challenges are formidable, but primarily ones of scale, cost, and labor.

Neural Wiring Data

A single neuron often extends its tendrils to touch thousands of others in a labyrinthine network. Wiring diagrams of these vast networks, called “connectomes,” are critical for understanding how neural circuits actually compute.

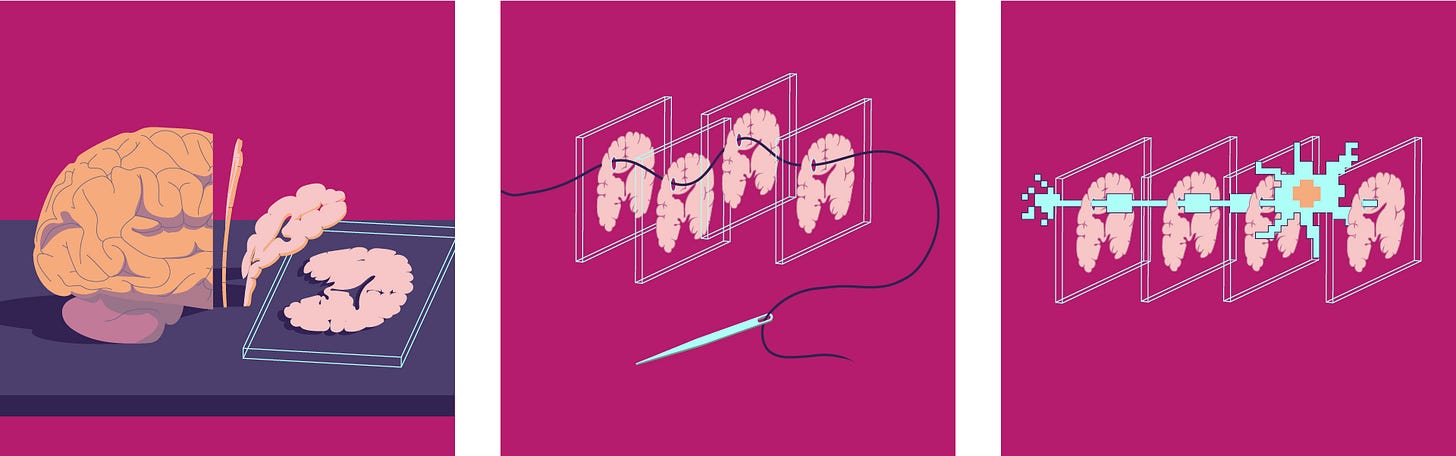

Broadly speaking, building a brain connectome demands four phases of work. First, researchers slice brain tissue into ultra-thin layers. Second, they image each with electron microscopes. Third, they use computer algorithms to stitch each image together into a detailed, 3D model, much like building a puzzle with millions of microscopic pieces. Finally, humans perform quality control on the output of the algorithms.

To reconstruct the connections between each neuron, images must have a high enough resolution to differentiate between even the smallest parts of a cell. Each pixel, in each image, represents about 10 x 10 x 10 nm³ of brain volume.8 After capturing millions of images, human proofreaders manually scroll through each one to spot split-and-merge errors from the neuron tracing algorithms. These errors occur when algorithms either fragment a single neuron into multiple pieces (split) or incorrectly combine distinct neurons into one (merge). Proofreading is by far the least scalable and most labor-intensive process in generating a connectome. For example, it takes 20 to 30 minutes to proofread a single image of a fruit fly neuron, but it can take 40 hours or more to proofread a substantially bigger mouse neuron with its more complex and multitudinous branches.

Since the first connectome of the worm C. elegans was published in 1986, nine additional worms and two fruit flies have had their wiring diagrams completely reconstructed. Meaningful amounts of brain tissue — such as regions of the spine in smaller organisms, or millimeter-scale volumes of larger brains — have also been imaged for ten additional organisms, but these data have not yet been proofread and thus are generally not usable for computational brain modeling.

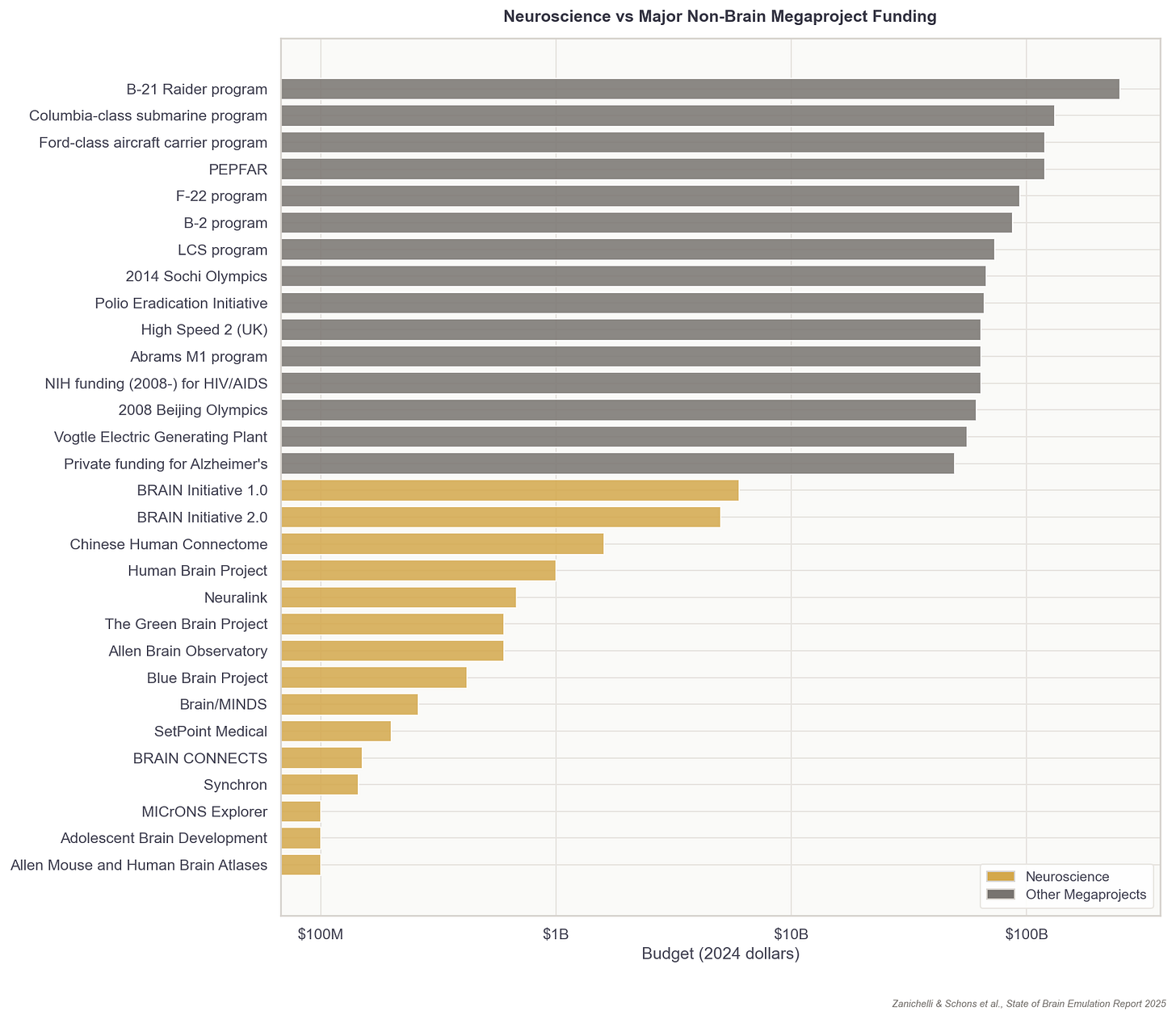

Fortunately, the total costs for reconstructing neuron wiring diagrams have fallen substantially over the last few decades. The average cost to reconstruct each neuron in the first worm connectome, published in the 1980s, was about $16,500. Recent projects now have a per-neuron processing cost of about $100 for small organisms, such as fruit flies. For rodents, with their more complex neurons, the price for proofreading alone is about $1,000 per neuron. To reconstruct a whole brain connectome, at an estimated cost of one billion dollars, these end-to-end prices must fall to $10 per neuron for the mouse and $0.01 per neuron for humans.

These falling costs apply to wiring data alone and are considerably higher for the “gold standard” data for brain emulation: datasets that merge neural wiring with activity recordings from the same individual organism. Such aligned datasets are much more labor-intensive to produce, but essential for building models that accurately capture both structure and function.

Researchers from Harvard, Janelia, and Google Research have been collaborating over the past five years to scale this approach of combined neural wiring data collection and neural activity recording from the same individual organism to build an aligned, whole-brain dataset. After hundreds of trial-and-error attempts, these researchers have recorded 70,000 neurons from one larval zebrafish during behavioral tasks and consecutively scanned the same organism’s brain tissue using an electron microscope. Neuron reconstruction, specifically the proofreading, was the most laborious part of this project and is still ongoing. However, the authors published the “Zebrafish Activity Prediction Benchmark” (ZAPBench) March of 2025 and expect the full connectome to be ready in 2026.9

Taken together, the tooling across computational neuroscience, neural recording, and neural wiring data has improved radically over the past decades. While capturing the full complexity of mammalian brains cannot be understated, the path to the first brain emulation models is now visible. And even if the journey is long, conquering each of the milestones along the way will be remarkable in its own right.

The Roadmap for Brain Emulation Models

I believe that to get to human brains, we first need to demonstrate mastery at the sub-million-neuron-brain level: most likely in zebrafish. For such organisms, like the fruit fly, a well-validated and accurate brain emulation model could be created in the next three to eight years. This claim is based on dozens of conversations with experts, as well as guesses informed by technological trendlines.

Achieving this goal will depend primarily on more and better data to fit parameters, which in turn is bottlenecked by funding and the achievement of some key technological breakthroughs. But there have been a couple of recent advances that will soon make this feasible: algorithms that eliminate human proofreading and methods to record neural activity over wider swaths of the brain. At the scale of insect-sized organisms, we are nearly capable of overcoming such bottlenecks.

Google Research recently released PATHFINDER, for example, a machine-learning-based neuron tracing tool that reduces human proofreading by about 80x. The key innovation is a neural network trained on thousands of human-verified neuron reconstructions, learning what real neurons look like: their branching patterns, curvatures, and proportions. When the system proposes merging two fragments, the model scores whether the result looks biologically plausible, automatically rejecting the kinds of errors that previously required human review.

This neuron tracing tool will undoubtedly be useful for ongoing, large-scale brain scanning projects. In 2023, the National Institutes of Health launched the BRAINS CONNECT project, which aims to scan about 1/30th of a mouse brain by 2028 and build infrastructure for a complete mouse neuron wiring diagram by 2033. The 2023 Report by the Wellcome Trust, mentioned in the introduction, concluded the main expenditure for such a project would be human proofreading, but algorithms like PATHFINDER may substantially reduce those estimates.

Another major boost to mapping connectomes is a technique called “expansion microscopy.” First reported in 2015, expansion microscopy iteratively expands tissue using polymers similar to the absorptive material found in diapers. In other words, rather than zooming into tissues using microscopes, this technique enables researchers to physically blow those tissues up, thus increasing resolution. The technology has gotten so good in recent years that scientists can now expand nanometer-sized structures, like synapses, to volumes large enough for standard light microscopes to take pictures and trace neurons; no more electron microscopes required.10

Expansion microscopy also addresses another key limitation of electron microscopes: namely, that they produce only grayscale images. While scientists can see cells clearly, they can’t easily tell what kind of neuron they’re looking at. Expanded tissue, by contrast, can be washed with fluorescent dyes that light up specific proteins of interest: membrane receptors, neurotransmitters, and other molecular markers that reveal how different neurons actually function.

The focused research organization E11 Bio is leveraging this molecular labeling capability to tackle the proofreading challenge. Rather than training algorithms to trace neurons more accurately through grayscale images as PATHFINDER does, E11 seeks to make neurons easier to distinguish in the first place. By tagging each neuron with a unique combination of protein “barcodes,” they give every cell its own color-coded ID. This would make it far easier for algorithms to trace neurons across thousands of images. E11 hopes this approach will make whole mouse connectomes feasible in the coming years.

Regardless of the approach, assuming proofreading will be basically automated in the upcoming years, additional small organism connectomes such as fruit flies would be in the low hundreds of thousands of dollars; a first mouse connectome in the low hundreds of millions, and a marginal one in the tens of millions of dollars. For human-scale brains, a simple extrapolation would yield 1,000x more: about a hundred billion for the first and tens of billions for consecutive ones.11

Many experts in the field share the conviction that we are on track to “solving” proofreading in the near term. Whole-brain, single-cell recordings, on the other hand, especially at the mammalian brain scale, will remain infeasible in the same time period. For any organism with a brain bigger than a cubic millimeter, we need to find innovative ways to compensate for the lack of comprehensive single-neuron recording coverage in our computational models.

For larger brains, we will likely increasingly rely on methods that can infer neural activity from structural and molecular data alone (which we can acquire in deceased brains at bigger and bigger scales). This approach remains speculative and, given how much promise it holds, surprisingly underexplored. Iteratively larger studies, probably in the tens of millions of dollars, could help determine the exact scale and type of data eventually required for mammalian-scale projects.

The vision of a digital, sub-million-neuron brain emulation model, however, also hinges upon a considerable investment, probably on the order of $100 million. With this amount, projects could funnel somewhat piecemeal research into an industrialized pipeline for recording and scanning state-of-the-art whole-brain datasets from multiple adult insect or developing fish brains. The aforementioned aligned zebrafish datasets have cost more than $10 million since inception in 2019, but subsequent ones should be much cheaper. Ideally, it would even be possible to rely on many replications and variations of such datasets, combining them with molecular annotation and other bespoke data acquisition techniques. This way, we can answer the question of what makes brain emulations better empirically, rather than relying on expert opinions. Also, it would provide space for investigations into neuroplasticity, as well as non-neuronal cell types and modulatory systems, all of which are likely core components of brain emulation models. Ultimately, models built upon such datasets would set a ceiling on today’s emulation abilities and, importantly, clarify the data needs for larger brains.

If I had to put a number on optimistic budgets and timelines for human brain emulation today, I would hazard: Conditional on success with a sub-million-neuron brain emulation model, a reasonable order of magnitude estimate for the initial costs of the first convincing mouse brain emulation model is about one billion dollars in the 2030s and, eventually, tens of billions for the first human brain emulation model by the late 2040s. My error bars on this projection are high, easily 10x the costs and ten additional years for the mouse, 20 to 50 years for humans.

Readers familiar with recent AI progress might wonder whether these timelines are too conservative. AI will provide extraordinary acceleration in some places, but I’m skeptical these gains will multiply across a pipeline with dozens of sequential dependencies and failure modes. Brain emulation is fundamentally not a digital process; Core bottlenecks involve physical manipulation of biological tissue, with time requirements dictated by chemistry and physics rather than compute power. The field requires deep integration across disciplines and tacit knowledge accumulated through years or decades of hands-on training. Capital costs of specialized equipment and ethical considerations around human brain tissue add to these constraints. Scientists might also make new observations tomorrow that complicate the picture further, such as realizing that not just a few, but hundreds of distinct molecular annotations might be necessary to accurately model a neuron’s activity.

Finally, it’s important to highlight that neither the sub-million-neuron organism nor the human estimates are considering brain models of a specific individual with all their memories and personality traits. Given that we will almost certainly aggregate data from many organisms to get sufficient data coverage, I expect the first brain emulation models to be generic, rather than personality-preserving. The feasibility of flawless transfers of a whole identity and its continuity onto a computer, as portrayed in science fiction, remains yet another step up the speculation ladder.

Despite these uncertainties, it seems we are the first generation of humans crossing the strangest threshold of all: from biology to technology, from evolution’s creation to our own. This refers not only to AIs simulating our behavior, but also to computer programs eventually emulating the very architecture of our brains. Before we can achieve this, there is a mountain of technical work and innovation to be done. The same holds for discussions surrounding the philosophy, ethics, and risks of brain emulation, which fall outside the scope of my investigations. Even so, what seemed absurd to me in 2023 now appears possible.

To learn more about brain emulation, see our full report.

Maximilian Schons, MD, is the project lead for The State of Brain Emulation Report 2025. His research consultancy focuses on responsible innovation at the intersection of biotech and AI. He has held senior positions in German medical research consortia and served as Chief Medical Officer for life-science startups. More at mxschons.com

Cite: Schons, M. “Building Brains on a Computer.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/92ye-82wp

Acknowledgements: Niccolò Zanichelli, Isaak Freeman, Anton Arkhipov, Philip Shiu, Adam Glaser, Adam Marblestone, Anders Sandberg, Andrew Payne, Andy McKenzie, Anshul Kashyap, Camille Mitchell, Christian Larson, Claire Wang, Connor Flexman, Daniel Leible, Davi Bock, Davy Deng, Ed Boyden, Florian Engert, Glenn Clayton, James Lin, Jianfeng Feng, Jordan Matelsky, Ken Hayworth, Kevin Esvelt, Konrad Kording, Lei Ma, Logan Trasher Collins, Michael Andregg, Michael Skuhersky, Michał Januszewski, Nicolas Patzlaff, Niko McCarty, Oliver Evans, Ons M’Saad, Patrick Mineault, Quilee Simeon, Richie Kohman, Srinivas Turaga, Tomaso Poggio, Viren Jain, Yangning Lu, Zeguan Wang, Xander Balwit, Robert Bölkow, Dion Tan, Felix Schons, Sarah Gebauer, Richie Kohman, Red Bermejo, Grigory, Ethan, Florian Jehn, Philip Trippenbach, Devon Balwit

… and to all the scientists and lab animals the research is based on. Any errors, oversimplifications, or misinterpretations are entirely mine. Illustrations and animations by Iris Fung.

Further reading

our 2025 full-length State of Brain Emulation Report 2025

Please send questions and comments to brains@mxschons.com.

The differences in architecture include the concept and level of detail of a neuron, the connection type, dynamics, and many other features.

The primary reason for this slowdown was not raw computing power, but communication. In a biological brain, neurons exchange signals almost instantaneously across short physical distances. Within a distributed simulation spread across thousands of GPUs, however, virtual neurons must constantly send messages to one another through interconnect cables linking each GPU. These interconnects can only shuttle so much data per second, creating a bottleneck. The GPUs end up waiting for information from their neighbors rather than crunching numbers.

State-of-the-art AI models, as of late 2025, have on the order of 1012 parameters. A mouse brain with 70 million neurons, each at 10,000 parameters, has roughly the same amount of parameters. A human brain would have ~1,000x more.

(1-2 TB memory and ~5-10 PetaFLOP/s vs. 1-3 PB memory and ~10 ExaFLOP/s). This assumes much better hardware than what Lu et al had access to in their 2024 paper.

Even better still is going beyond a purely observational setting and introducing active perturbations, targeted activations and inhibitions of neurons, while recording.

This is what companies like Neuralink employ. The Neuropixel is the most commonly used device in neuroscience. Usually, they rely on one “needle” thread that has hundreds or thousands of recording spots. Neuralink utilizes 64 individual threads.

70 million and 86 billion neurons at 200 Hz.

This volume is extremely small: approximately the same as 100,000 carbon atoms in a diamond.

Another, arguably more famous, project that also collected an aligned dataset is the IARPA MICrONS project. The consortium collected both activity and wiring reconstructions across a cubic millimeter of mouse brain, but the proofreading process is still ongoing.

For physical reasons resolution of light microscopes is limited to about 200nm. Many structures are 10 or 20 times smaller than that, which is why electron microscopy used to be the only feasible path. Scientists overcome this barrier by literally expanding tissue by the factor necessary to image at the limits of what light microscopes can resolve.

Here I assume current costs for microscopes, storage, etc. The reason for the difference in initial and marginal costs are the substantial up-front costs, in particular for microscopes. Once these are paid for, the marginal costs are tissue processing, storage, and compute.

... if one is able to emulate a human brain in sufficient faithfulness to be experimentally useful, does that not also imply one has created an emergent human mind that is due the same ethical protections as a biological human?

Excellent analysis, it's fascinating to see how your perspective on brain emulation has evolved since you first discussed the challenges, truely highlighting the rapid progress in the field.