The Sunlight Budget of Earth

Sunlight represents a seemingly endless source of largely untapped energy. Just how endless is it?

By Sam Clamons

Editor’s Note: This article contains numerical estimates compiled from various research articles. It was reviewed by three climate experts: Casey Handmer, Paul Reginato, and Jonathan Burbaum. Their notes are recorded in the footnotes. Our full dataset and calculations are available for download. We hope this will be a useful starting point for much deeper discussions.

Modern biotechnology is powered by sunlight. Light-gobbling algae, both natural and engineered, are harvested and squeezed for biofuels or dried and pressed to make shoes. We use sugarcane and sugar beets — essentially autonomous, self-replicating, solar-powered biofactories — to mass-produce sugar. That sugar, along with hydrolyzed yeast,1 form the basic media used to grow genetically engineered E. coli, yeast, and other microbes that make various medicines and foods. At some point in the supply chain, nearly every bioengineered product either is a solar-powered plant or derives its energy from one.

Sunlight is an exquisite energy source. It’s abundant, renewable, and cheap to access. Its consumption produces no greenhouse gasses or toxic byproducts. However, “renewable and abundant” is not the same as “infinitely abundant.”2 Wildlife, agriculture, and solar electricity generation all use sunlight, too. In principle, all of these processes compete for photons. A joule absorbed to synthesize plastic precursors in an algae can’t also be used to feed a tree or charge a cell phone.

Fortunately, there is a lot of sunlight to go around. While humanity might be forced to make trade-offs between wild plant life and food for humans in the future, it won’t be because we run out of sunlight.

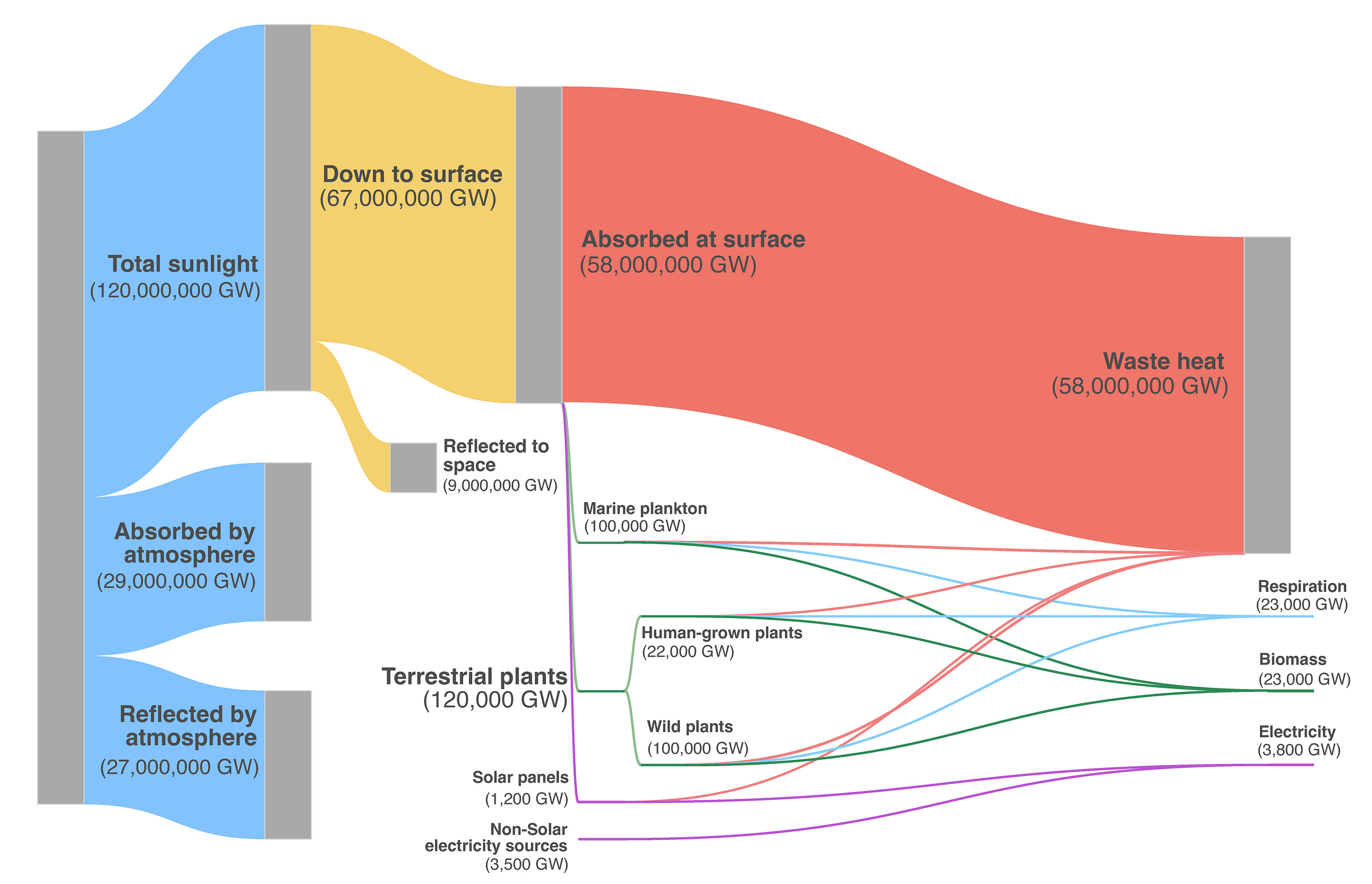

To get a sense of where sunlight goes, we can compare the sunlight inputs to our most sunlight-intensive industries — solar power and agriculture — to the sunlight used by wild organisms, while also accounting for the photons that do nothing but heat the ground or bounce right back into space. These numbers are important enough that scientists around the globe have put effort into estimating them. Just note that these are estimates rather than direct measurements, and they vary between sources. Collectively, these estimates give us an order-of-magnitude picture of Earth’s sunlight budget.

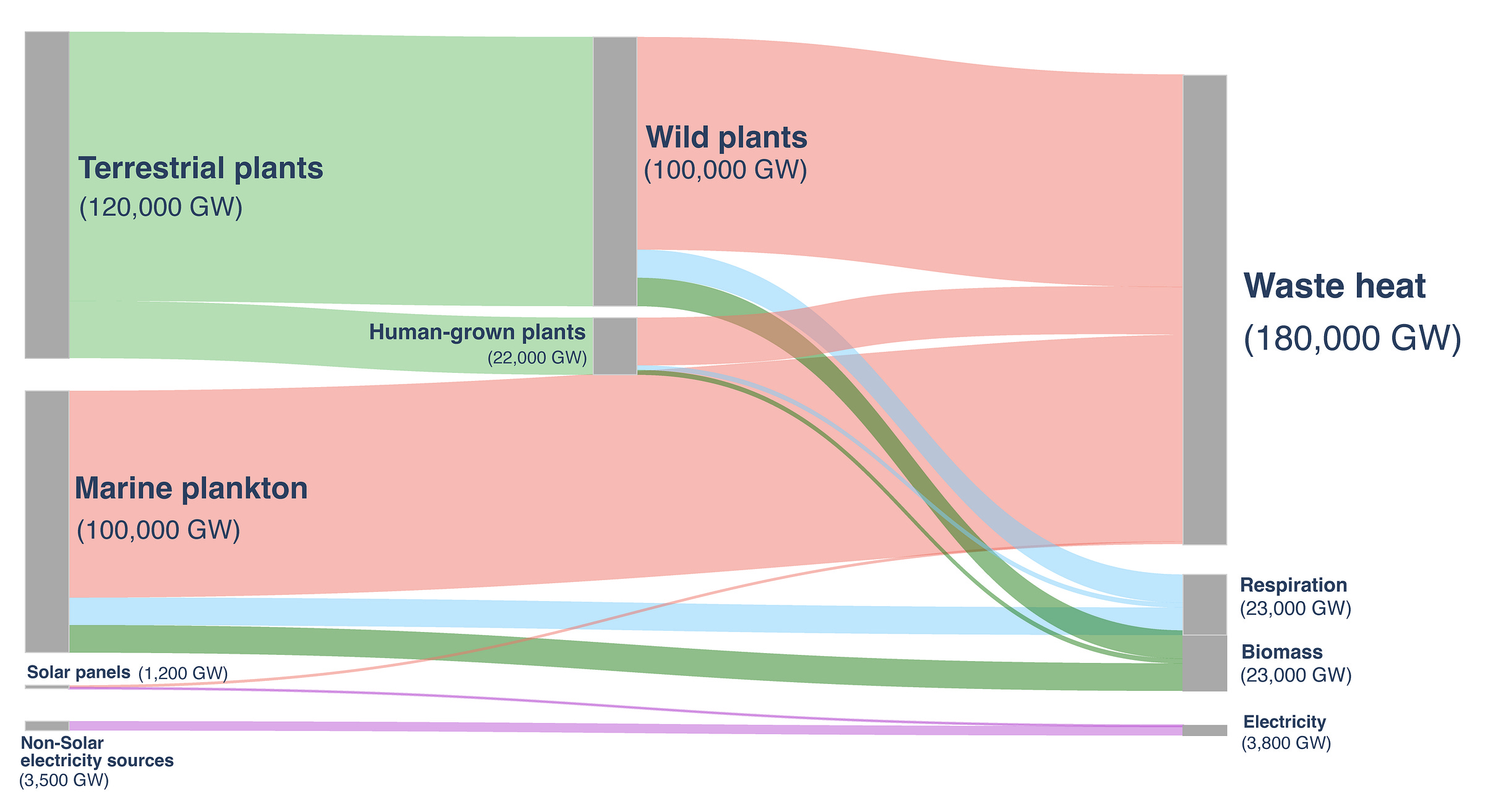

Solar power generation is relatively easy to account for. The Energy Institute’s 2025 Statistical Review of World Energy estimates that humanity’s solar industry currently soaks up sunlight at a rate of approximately 1,200 gigawatts (GW),3 of which about 240 GW is usefully converted to electricity. If we were to expand our solar capacity to match current global electricity demand at the same conversion efficiency,4 that absorption would balloon to about 18,000 GW.5

What about human agriculture? Figuring out the total amount of sunlight used by humans worldwide is no easy feat, but several groups have attempted it. One somewhat dated but thorough example from 2007 comes from Helmut Haberl and his six co-authors at Klagenfurt University, who use a combination of global crop yields published by the Food and Agriculture Organization and land-use estimates based on satellite imagery. They estimate that human-managed crops, wood, and grazing land together fix about 8 billion metric tons of carbon each year. We can convert carbon mass to stored energy using the energy content of glucose,6 which comes out to about 1,700 GW. We must also adjust this number upward by 30 percent to account for the increase in agricultural production since 2007.7

Different plants convert sunlight to sugar at different efficiencies. A theoretical-best-case estimate comes out to about 10 percent efficiency.8 This estimate begins with successfully-absorbed photons9 and ends with final accumulated biomass (for C3 plants, those that use the Calvin cycle for carbon fixation and make up the bulk of plant productivity worldwide) to arrive at 22,000 GW of sunlight absorbed — pretty close to the amount of sunlight required for current global electricity needs.10

Determining nature's use of sunlight is more complicated. Natural ecosystems are massively more complex and diverse than agricultural fields, so any estimate of natural photosynthesis will come with large error bars. Nevertheless, there have been rigorous attempts.

Haberl et al. lean on a modified version of a complex model called LPJ-DGVM,11 which describes flows of carbon and water between plant life (broken down into ten subtypes, such as “tropical broadleaved evergreen tree” and “C3 perennial grass”), the atmosphere, and multiple different kinds of soil, all as a function of climatic variables like sunlight, temperature, snowmelt, and more. Feeding the model detailed satellite data, they estimate total global, wild plant productivity at about 50 billion metric tons of carbon per year, which, using the same methods as before, equates to about 120,000 GW of sunlight absorbed by terrestrial plants.12

That estimate doesn’t even include photosynthesis in the ocean, which is itself substantial. Plants, it turns out, don’t account for very much of total marine productivity. Instead, almost all photosynthesis in the ocean is done by a combination of cyanobacteria and single-celled eukaryotic algae like diatoms and dinoflagellates. We don’t have the same kind of census-based models, like LPJ-DGVM, for oceanic plankton that we do for terrestrial plants. Instead, oceanographers measure the sum total of photosynthesis in any particular spot of ocean using one of the following methods: by measuring changes in dissolved oxygen content as a proxy for photosynthesis; by tracing carbon isotopes, using principles similar to carbon dating to estimate carbon absorption rates; and by using fluorescence to estimate concentrations of various kinds of chlorophyll, and by proxy, amounts of photosynthesis.

Marine researchers have taken numerous such measurements all over the world and across seasonal cycles. Several groups have combined all that data, arriving at different estimates of total marine productivity, but they trend around 50 billion metric tons of carbon per year — almost exactly the same as the total productivity of land plants.

By putting all of this together, it is possible to estimate human sunlight usage. On the scale of all productively-harvested sunlight, all human solar use (most of which goes into cultivated crops) adds up to about 11 percent of the energy input to wild photosynthesis.13 We’re more than a rounding error next to natural photosynthesis, but we’re hardly a competitive rival. Almost all anthropogenic sunlight capture is through plants, though this would change if we substituted solar for most of our existing power sources.

To keep this number in perspective, though, all of the solar panels, lumber forests, grazing lands, crop fields, wild plants, and oceanic phytoplankton combined only account for about 0.5 percent of all the sunlight absorbed at the Earth’s surface. Both nature and humanity have only just begun tapping into the awesome potential of sunlight.14

The vast majority of solar energy is either never taken up by any of Earth’s systems or is simply absorbed as heat. To be clear, “absorbed as heat” is the eventual fate of nearly all sunlight captured anywhere on Earth by anything.15 Energy captured by a solar panel might charge a battery, but every time that battery is discharged in the course of doing something useful, some (usually most16) of that energy is dissipated as heat.

The same is true for a plant — approximately three-quarters of the chemical energy that goes into synthesizing a molecule of glucose is released as heat. That glucose might be burned to power other reactions or might be consumed by another organism, but most of its energy will be dissipated every time it changes hands. The heat energy will slowly bleed out as new photons, mostly in infrared wavelengths, which may be reabsorbed into heat again or may fly off into space, leaving the Earth a little bit colder. Ultimately, every photon absorbed by the Earth is transient, here just long enough to be split into several weaker, higher-entropy ones. A few do something useful for something alive on this journey, but most don’t.

So just how much sunlight is “wasted” in conversion to heat17 without either feeding an organism or providing utility as electricity?

To begin, roughly half of all sunlight — enough to power all of human civilization sixteen thousand times over — is either absorbed or reflected by the atmosphere. Another 9,000,000 GW (~15 percent of the light reaching the ground) is reflected straight back into space. And, of course, all of this waste pales utterly compared to the 10 billion Earths’ worth of sunlight that misses the planet entirely!

Now, before we begin dreaming up ways to hold on to more of the sun’s energy, we should remember that holding onto more sunlight is exactly how we got global warming. We may do better to figure out how to get more sunlight to reflect back into space, not less. It wouldn’t take much, proportionally speaking — Earth is currently absorbing a net of 0.6 W/m2 out of 340 W/m2 of incoming sunlight, suggesting that we would only need to reflect an extra 0.6/340 = 0.2 percent of sunlight to approximately offset current levels of greenhouse gas warming.1819

Even with this added consideration, there is a lot of room to improve how we use the light we get. Wildlife may consume 10 times as much sunlight as humanity, but even nature only uses about 0.5 percent of the sunlight absorbed at ground level! That means the vast majority of sunlight — roughly 200 times the total captured by all ecosystems — is absorbed without contributing to photosynthesis. This includes light falling on deserts and snowfields, light absorbed by the ocean before it can reach plankton, and light that slips through forest canopies or grassland cover without being used.

But if there’s so much wasted sunlight bouncing around, why hasn’t life already evolved to take advantage of it? Wild ecosystems are packed full of millions of species of photosynthesizers, each constantly adapting to more efficiently consume the resources at their disposal. Why are they leaving so much energy on the table?20

This is largely because energy isn’t actually what limits most of Earth’s primary producers.21 Photosynthesis doesn’t just take energy — it also takes water and carbon dioxide. Water limits growth more than sunlight in, for example, deserts. Meanwhile, carbon dioxide is generally plentiful on land22 — but so is oxygen, which inhibits photosynthesis at high enough concentrations.23 And even if organisms had infinite access to photosynthesis, life can’t be built from glucose alone. Proteins require elemental nitrogen in a bioavailable form, and DNA and RNA require both nitrogen and phosphorus, both of which are rare relative to CO2 and water. Iron and silica salts are similarly limiting for marine phytoplankton.

This is how agriculture can be deeply disruptive to natural ecosystems, despite using only a small fraction of the sunlight — light simply isn’t what we’re competing with nature for. Human agriculture currently takes up an estimated 45 percent of the world’s arable land.24,25 It needs that land for its water, soil, and nutrients; not for access to limited sunlight.

Solar farms can also compete with nature for land. The most cost-effective forms of solar power have always been large, contiguous utility-scale farms, typically built by leveling large areas and paneling them with silicon collectors, mirrors, or some equivalent light-harvesting machinery. It’s not as disruptive to wildlife as covering the landscape in parking lots and houses, but it’s close.

Fortunately, solar power doesn’t have to be this destructive. For one thing, we have a lot of already-degraded land that we can build solar panels on, including houses, office buildings, malls, roads, and parking lots. Alternatively, solar panels can be used to support plant growth instead of replacing it, in a practice known as agrivoltaics. Many crop plants actually grow better with some shade, and solar panels create cool, moist microclimates that are healthier for many animals — including sheep — than an open field.

We don’t even need to use solar panels to better capture underutilized solar power. Once light has been absorbed as heat, it can still be used. Wind, for example, is largely powered by the temperature gradients produced by mass absorption of sunlight,26 ultimately making it solar power with extra steps. Wind also supplies most of the energy in ocean waves, so wave power, too, is solar power.27 Even fossil fuels are just compressed and stockpiled plant matter — hundreds of millions of years’ worth of collected solar energy now being burned off as heat in a geologic instant.28

Solar farms already face protests over land use. We should expect to see these intensify as the industry scales up. Agricultural land used for large-scale engineering products (or to grow feedstock for those products) will be in even more direct competition with existing wildlife and with food production. But this won’t happen because we “run out of sunlight.”29 Instead, competition will be over water, land, fertilizer, or other resources — or because we simply haven’t been clever enough about how we use the ultra-abundant energy at our disposal.30

Samuel Clamons is a bioinformatics scientist at Illumina, Inc. with a PhD in Bioengineering and training in applied mathematics and computer science. Outside of his day job, he writes science fiction and researches theoretical questions in biology at Asimov Press.

Cite: Clamons, S. “The Sunlight Budget of Earth.” Asimov Press (2025). https://doi.org/10.62211/39qp-47hf

Header image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Feed-stock yeast is generally not itself genetically modified, but is often grown on GMO-derived sugars.

Reginato: The solar budget is depletable in space, just not in time.

A watt is a rate of energy production/consumption of 1 Joule per second, or roughly one percent of the power output of a human. A gigawatt is a billion watts, which is roughly the energy output of the population of London or of a typical nuclear fission plant.

If solar power capacity continues to grow at its current exponential growth rate, we’ll hit 18,000 GW around 2040. Then again, at that rate of exponential growth, we’ll absorb more light than is received by the entire Earth in about 2070, so growth will probably level off sometime in the 21st century.

Numbers for various kinds of electricity production are pulled from the datasets underlying the Energy Institute’s 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy. The amount of sunlight absorbed depends on the efficiency of the world’s solar electricity production, which has changed dramatically over time. For estimation purposes, I’ve assumed 20 percent efficiency, which has been the number commonly given for “modern” (but not state-of-the-art) utility-scale solar systems over the last couple of years.

For the details of this calculation, see the “Terrestrial net productivity (all human)” entry in our data and calculation spreadsheet.

Based on the combined production by mass of cereals, corn, dry beans, soybeans, sugar crops, potatoes, and tomatoes in 2007 and 2023, as reported by Our World in Data.

Handmer: This is an order of magnitude higher than the ‘efficiency’ of photosynthesis you’ll find anywhere else. That’s because ‘absorbed photons to biomass’ is an unusual way to talk about ‘efficiency.’ A better apples-to-oranges metric (and a more common one) compares incident light (e.g., 1 kW/m2) to useful energy (such as photovoltaic power at maximum power tracking point vs. accumulated biomass enthalpy). If we do that, the efficiency of the best plants under the best conditions at the peak of their growth is about 1 percent.

Author’s response: For this piece, I wanted to understand how much light energy plants actually capture, separately from how much light energy they theoretically had available. Thus the unusual measure.

This is only looking at efficiency after losses from reflection, transmission, and wavelengths of light plants can’t absorb.

Burbaum: If you just want global numbers (and don’t care about breaking down human vs. wild use), there is a much easier way to estimate the photons used in photosynthesis: Look at satellite chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, which directly translate into GPP (Gross Photosynthetic Productivity). The only conversion needed depends on the biochemistry of the plant. In most parts of Earth, it's C3 metabolism, but in grasslands (including corn agriculture) it's C4, those plants that photosynthesize via the Hatch-Slack pathway, while in deserts it's CAM, a water-conserving method of photosynthesis. Interestingly, the annualized global max GPP is in the rainforest, but the max GPP is in Iowa. CAM is a rounding error, and you can safely assume that C3 will dominate. C4 fixes carbon twice, so it's more carbon efficient but less energy efficient, explaining why C3 forests can dominate fast-growing C4 grasses. You can also look at the amplitude of the Keeling Curve, caused by seasonal variations in the amount of sunlight hitting land. There are ocean-based photosynthetic systems as well, but they tend to use carbonate species rather than dissolved CO2, and the equilibrium is slow (which is why ocean acidification lags CO2 increase).

“LPJ” are the last initials of the three authors most associated with the model; “DGVM” stands for “Dynamic Global Vegetation Model.”

Burbaum: Some groups claim that all this oceanic fixation has a huge impact on atmospheric carbon. The Keeling Curve asserts differently. Possibly true for total carbon fixation, but ocean fixation does little to diminish GHG. Again, the equilibration between CO2 and carbonate species is slow. Dissolved carbon and gaseous carbon are different pools. This is, as far as I know, a very common misconception.

11 percent = (22,000 GW into agricultural plants + 1,200 GW into solar panels) / (120,000 GW into terrestrial plants + 120,000 GW into oceanic plankton and cyanobacteria).

Burbaum: I think others have looked at the ‘appropriation’ of photosynthesis for human uses, and it's a fairly large number. So, I question this assertion. It's slightly disingenuous to make the denominator ‘all the sunlight.’” For example, I've done a LOT of thinking about the water cycle: Solar energy drives the weather, so rainfall is one consequence. Do you count it as a human use when considering Iowa corn, which is mostly rain-fed? What about hydroelectric power?

Author response: The reviewer is right to point out that sunlight does useful work even after it’s dissipated as heat. But I think we can still think about how much is used vs. wasted up to that point.

Burbaum: It depends on what you think of the chemical energy stored in biomass — predominantly as reduced carbon. It's a small amount, but with millions of years of solar irradiation as the denominator, it has added up over time. Physicists would love to ignore it, but we have built modern society on it. Some models actually make that assumption, but the amplitude of the Keeling curve is several times larger than the slope, showing that photosynthesis driven exchange with biomass is much larger than the amount of carbon we lowly humans add.

Handmer: This says more about battery efficiency rather than downstream uses.

To be clear, heat energy can still do useful work, like evaporating water and driving rainfall. But light energy can become that heat energy in more or less useful ways.

Handmer: Say, via solar radiation modification with sulfur.

Burbaum: Some are working on this, but it has acquired the label of “geoengineering,” which has negative connotations. We could solve all of our energy needs for a very long time with fission-based nuclear, too.

Burbaum: Look at Graham Fleming's work (University of California, Berkeley) … the photosystems in a chloroplast are a perfect solar panel, with nearly perfect efficiency when the metric is splitting water. They leave NOTHING on the table. The thing is, photosynthesizers (which all use essentially the same chloroplast chemistry) are living in a world of too much energy, and are all competing against others for survival. Plants in open sunlight have to avoid sunburn, so they dissipate the energy through NPQ (non-photochemical quenching), mostly as heat. As we all know, it's easier to go down in energy efficiency than it is to go up.

Handmer: It is also important to note the fundamental fact that solar PV can generate useful mechanical or chemical work with about 100x higher efficiency than biomass.

Burbaum: I think paleobiology would beg to differ. We're actually fairly close to a minimum in CO2. Consider that essentially all of the oxygen in the atmosphere (~20 percent) was produced by photosynthesis, meaning that ancient atmospheres must have had about this much CO2. I have to give credit to Eric Toone for that observation, when confronted with ‘peak oil’ as an argument. Also, before chloroplasts, most life on earth was purple and driven by chemistry similar to that in our eyes. Once chloroplasts started pumping out oxygen, this killed most life that existed before (except in oxygen-depleted salt marshes). At least that's what the folks who study that sort of thing think.

C4 plants have adaptations that allow them to effectively photosynthesize in oxygen-free compartments, which makes them much more efficient producers. Why don’t all plants have C4 adaptations? Because C3 turns out to be more efficient when atmospheric CO2 is abundant and temperatures are low, as has been the case for most of the history of plants. Plants are in the middle of a 30 million year (so far) transition from C3 to C4.

Burbaum: The evolutionary nugget here is that chloroplasts evolved in an anaerobic environment. The core chemistry, carboxylation of a tertiary ribulose bisphosphate carbanion as a nucleophile and CO2 as an electrophile, works very well. But it cannot exclude oxygen from the active site of the enzyme. When oxygen is present, the energy is wasted. That's the core innovation of C4 biochemistry — CO2 is fixed once to form malate, which is then transported to an organelle where the CO2 is released into an anaerobic environment and fixed a second time using RuBisCO.

Whether that fraction goes up or down before the 2080s, when the world’s human population is expected to reach its maximum, remains to be seen. On the one hand, we expect to be feeding about 25 percent more humans. On the other hand, “simply” switching to a plant-based diet would cut down humanity’s arable land needs by an estimated 75 percent.

Reginato: It’s worth doing a land use comparison. We're using way more than 7.5 percent of arable land, so our activities are effectively decreasing solar energy utilization. Land use comes up later, but calculating the inefficiency we introduce could be interesting.

A negligible amount of wind energy also comes from tidal forces, which act on the atmosphere in much the same way as they act on oceans.

Mostly. Waves do get a small amount of energy from other sources like tidal forces.

Heat released by combustion isn’t what causes global warming — that would be the sequestered greenhouse gasses — but it is where most of the stored chemical energy of fossil fuels goes, ideally after first doing some work in the form of moving a car, lighting a room, or driving a calculation.

Handmer: In the U.S., we already waste 50 million acres of ecologically productive land for subsidized corn ethanol. 50 million acres of solar would produce 18 TW, enough for the whole world's electricity supply and in a space about half the size of Nevada.

Handmer: The big question that's missed here is that the economic productivity of prime agricultural land is a few hundred dollars per acre per year, but the economic productivity of an acre powering AGI via solar is 1000x higher, which is an irresistible forcing function towards paving the earth with a solar output we can't eat.