Model Organisms Are Not Static

A research study reveals that some vertebrate genomes mutate 40-times faster than others.

About 70 percent of scientists say they have tried and failed to reproduce an experiment performed by their peers. And animal studies are, perhaps, among the least reproducible of all experiments because, in an effort to reduce the number of animals used in research, scientists often avoid repeating them to confirm positive results.1 When animal studies are replicated, however, they often yield different outcomes.

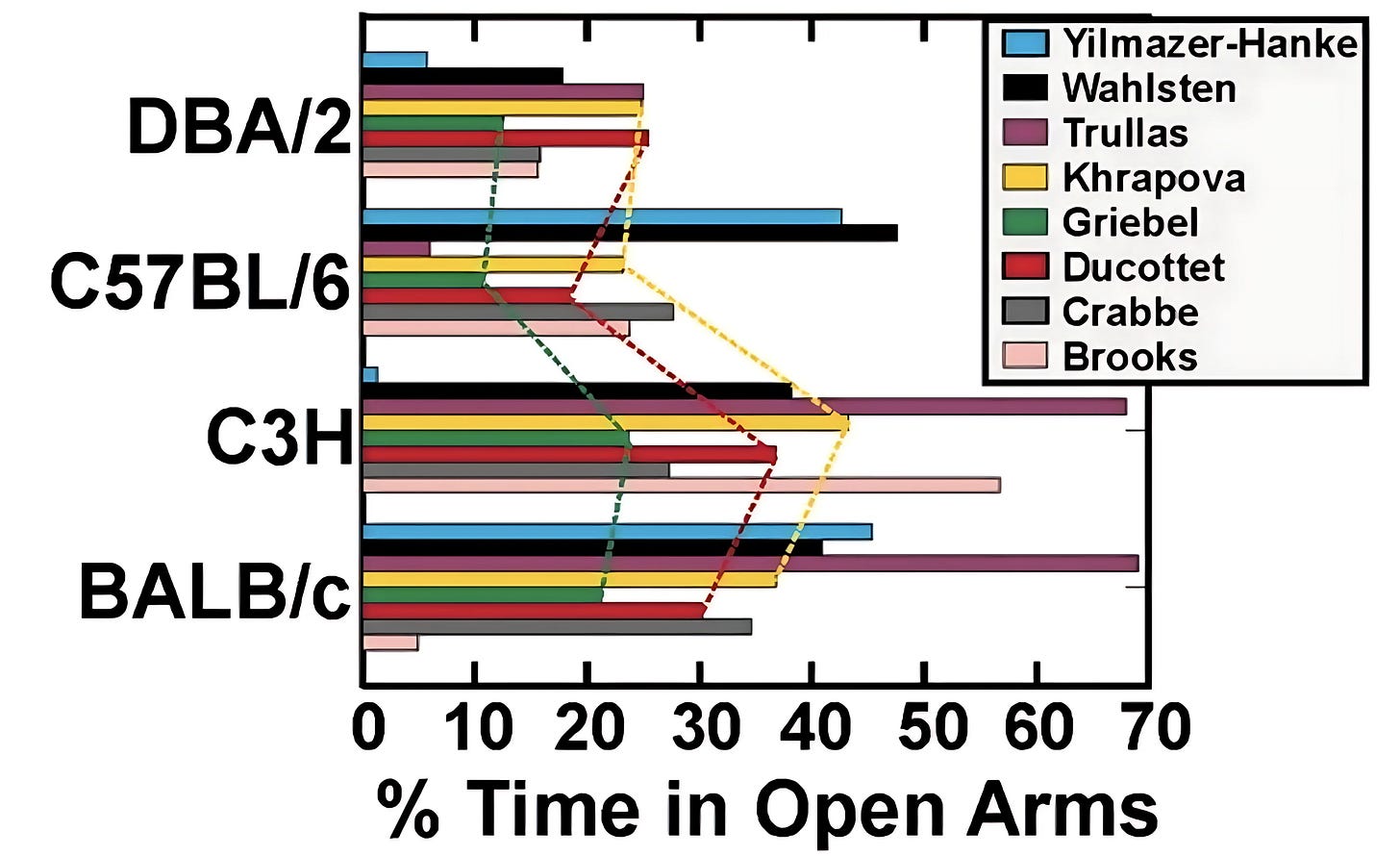

In 2006, researchers at the University of Alberta tried to replicate a 1993 mouse study. But they found that the stress levels of their mice, when put through an anxiety-producing maze, differed from the original data. They attributed this discrepancy in results to minor variations between laboratories, but could something else have been amiss?

Genetics are partly to blame. Compare the genomes of any two animals of the same species living in the wild, and they will bear numerous genetic differences. Random mutations in DNA bring about this genetic variation, and mating between unrelated individuals mixes the mutations amongst the population.

Compare two members of an inbred model animal strain, however, and they will have nearly identical genomes. This is by design, and those genetic similarities are painstakingly maintained to minimize the extent to which genetic variation distorts results. Even so, researchers and animal model suppliers can’t completely prevent mutations — and that could skew experimental results.

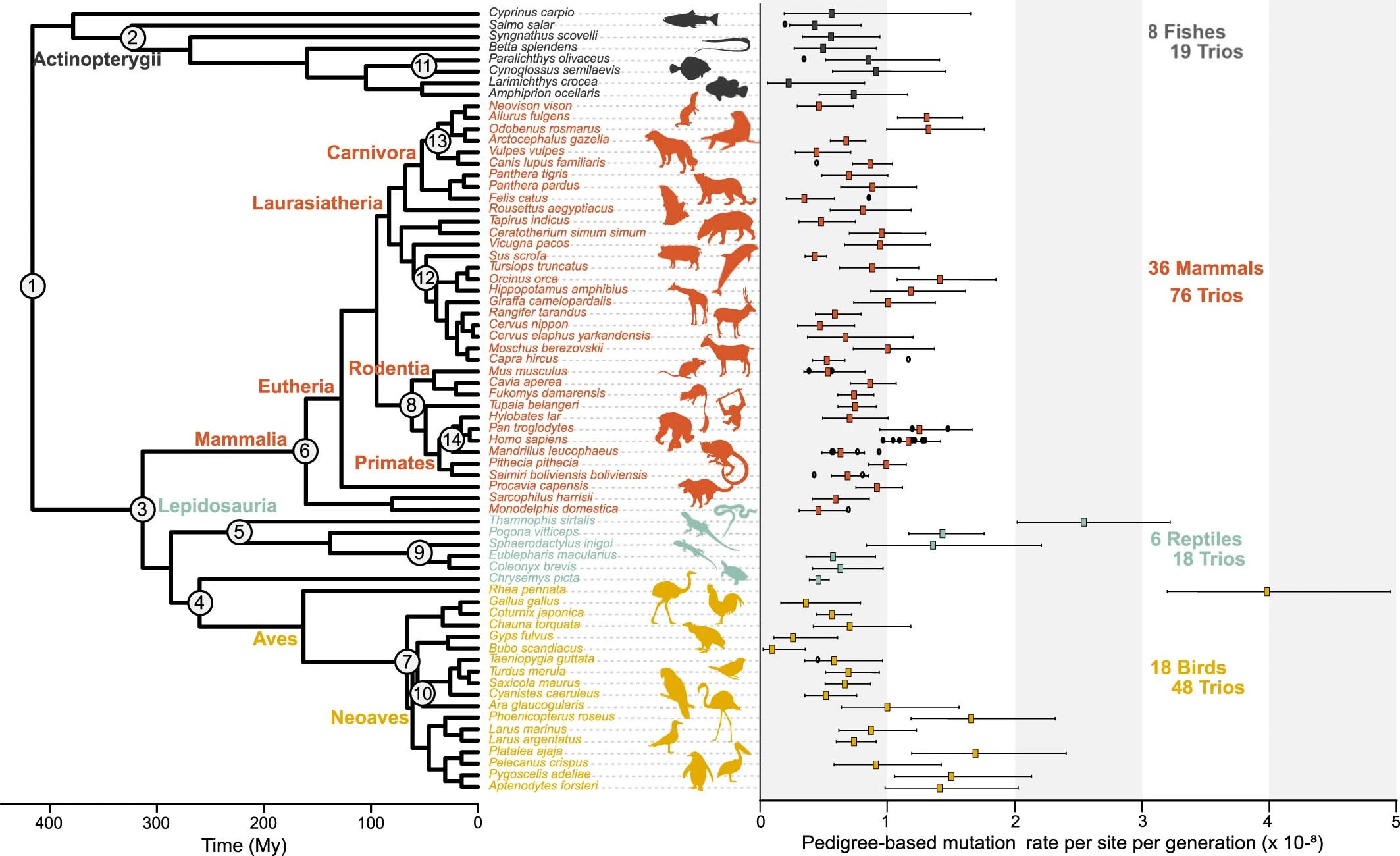

In 2023, for example, ecologists at the University of Copenhagen showed that the number of mutations arising in each generation differs by up to 40 times between 68 species of vertebrate (backbone-bearing) animals, including birds, fish, mammals, and reptiles. Species more prone to genetic mutation are likely to change their characteristics more quickly.

Most vertebrates in the study, including the lab mouse, Mus musculus, acquire one mutation for every 100 million DNA bases per generation. If you factor in the genome size of the mouse, this implies that pups acquire 15 new mutations, on average, compared to their parents. The mouse genome changes much faster than the snowy owl’s (one mutation per progeny) but much slower than Darwin’s rhea bird (about 47 mutations in every offspring).

The researchers didn’t look at every model animal in their analysis, though. Common model vertebrates excluded from the study include the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, and the zebrafish, Danio rerio — both of which are linchpins of embryology research. It may also be worth exploring germline mutation rates in model invertebrate (backbone-lacking) animals, such as the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. But still, the vast differences between vertebrates that the scientists did study should compel others to explore how quickly the genomes of other model species change.

Animals build up mutations in their cells throughout life, often because mistakes happen during DNA replication. For this study, though, researchers focused solely on DNA changes in the germline, or the lineage that gives rise to sex cells. Germline mutations don’t typically affect the parents’ characteristics, but are passed down to their offspring.

Population geneticists argue that mutations are deleterious more often than beneficial because they tend to disrupt intricate gene pathways rather than refine them. Natural selection in the wild generally stamps out deleterious errors, meaning fewer germline mutations are retained in the population. That may not be the case with animal strains bred in the lab, though, where reproduction is tightly controlled. Rather than allowing the “fittest” animals to mate by natural selection, scientists contrive breeding between related or well-characterized animals, even if — unbeknownst to the specialist — the animals carry mutations. This can cause deleterious mutations, which natural selection would not favor, to become more frequent in the population over many generations.

Animal facilities also tend to house small cohorts compared with wild populations, which adds to the problem. Small populations increase the odds that deleterious mutations persist. In the wild, where there is enough competition and choice, animals with genetic faults are least likely to reproduce. But in a small, confined community, their chances increase.

The Jackson Laboratory, which breeds and sells mouse strains, tries to minimize the retention of germline mutations down generations. As biotechnologist Alex Telford has written for Asimov Press, the Jackson Laboratory cryopreserves mouse embryos for common strains at their main campus in Maine and backup facilities elsewhere. Technicians thaw these mouse embryos once every five years, allow them to develop, and then breed those embryos to “reset” their genomes. This reduces the rate of genomic change by 20 to 50 times, they say, but doesn’t completely prevent it. The mice still acquire and pass on mutations during the half-decade intervals.

Now that we know every mouse pup acquires 15 new mutations, a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation quickly reveals the impact over a five-year span. It takes mice three months to develop from fertilized eggs into sexually mature adults. Assuming those mice breed as soon as they reach maturity, then 20 generations will occur over five years. By multiplying the number of generations by the number of mutations per generation, we can estimate that these mice will accrue roughly 300 mutations by the end of the five-year period.2

Most of these 300 mutations will not affect protein-coding genes, which make up only 1.5 percent of the mouse genome. Only 4 or 5 mutations, in total, will be located in protein-coding regions. Some of these mutations may alter a protein sequence, but this doesn’t guarantee a change in the protein’s function: A mutation might affect a dispensable amino acid, such as one not involved in an active site, or it may swap a functionally-important amino acid for one with similar properties, such as a similar polarity or charge. Some of the mutations may not alter the amino acid sequence at all because there are redundancies in the genetic code that allow multiple triplets of DNA bases to code for the same amino acid.

The mutations are far likelier to affect the remaining 98.5 percent of the mouse’s DNA. Some of these regions play important roles in regulating genes through elements like promoters, enhancers, and silencers. Others express non-coding RNAs, including amino acid-carrying transfer RNAs pivotal to protein synthesis, or microRNAs that trigger the breakdown of messenger RNA and inhibit gene expression. Thus, a buildup of 300 germline mutations is more likely to alter the regulation of protein-coding genes, rather than their sequences.

These mutations may partly account for the reproducibility crisis. As Telford notes, a gene previously found to be toxic in the liver of a mouse strain appeared to protect liver function when introduced into distantly related mice of the same strain, potentially because of mutational differences. Keeping track of these mutations could be time-consuming and expensive, especially if one considers that genomes will vary across mouse facilities where the animals inherit different complements of mutations.

Nonetheless, scientists may want to consider more frequent sequencing of their mouse strains, or more frequent assessments of differences in their gene regulation patterns using transcriptomic or proteomic analyses. The resultant data could allow them to exclude mice with genetically altered characteristics from breeding programs.

Recognizing the threat genomic change poses to reproducibility, researchers are starting to cryopreserve other animal model embryos to limit the burden of mutations. Fruit fly researchers at the University of Minnesota in 2021 developed a method to freeze fly embryos that involves injecting them with a cryoprotectant — a chemical that prevents ice from expanding and bursting the cells — before rapidly plunging them into liquid nitrogen. At Szent István University in Hungary, researchers aim to devise protocols to freeze zebrafish embryos, but they must first find a nontoxic cryoprotectant.

Biologists strive to obtain as much information as possible from models; working with animal cells, they use high-throughput techniques like single-cell RNA sequencing to explore differences in gene expression, proteomics to study how protein levels vary, and epigenetic profiling to see how the tight packaging of DNA regulates genes. Now more than ever, researchers may be inadvertently recording characteristics attributed to the accrual of germline errors.

As mutations quietly rework the genomes of our most trusted model species, scientists face a clear choice: Confront the variability head-on or risk compounding the reproducibility crisis with every passing generation.

Kamal Nahas is a columnist at Asimov Press.

Cite: Nahas, K. “Model Organisms Are Not Static.” Asimov Press (2025). https://doi.org/10.62211/83hr-49kj

Lead image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Correction: An earlier version misstated the percentage of experiments that cannot be reproduced.

Scientists who perform in vitro experiments tend to repeat an experiment three times to test the consistency of their results, but those who work with live animals often repeat experiments only once to see if the findings match.

In every round of breeding, mice will harbor roughly 15 new mutations plus the germline mutations from previous generations. If each parent has N germline mutations, and they donate half of their DNA to their offspring, they will pass on N/2 mutations. The offspring will receive N/2 mutations from both parents, cancelling out the division: (N/2)x2=N. Thus, the calculation becomes N multiplied by the number of generations.

"Scientists are unable to reproduce experiments performed by their peers about 70 percent of the time. This is true across fields, from domains as disparate as cancer biology and psychology."

That is not what the cited article says, at all. The only mention of 70 percent in the article is here: "More than 70% of researchers have tried and failed to reproduce another scientist's experiments, and more than half have failed to reproduce their own experiments."

That is to say, the 70% refers to a fraction of researchers, not a fraction of experiments/papers.

They do give numbers for what fraction of papers could be reproduced elsewhere in the article, but *only* for cancer biology and psychology, and only from two studies -that is to say it cannot be extrapolated across fields. The numbers they give are 10% for cancer biology and 40% for psychology, which would translate to 90% of cancer papers and 60% of psychology papers being irreproducible, respectively. If you average that out you get 75%, which is at least close to 70%, but, again, this number cannot be extrapolated across fields, and as the article states, there is no real consensus on what the true number is for any given field, let alone across research as a whole:

"The results capture a confusing snapshot of attitudes around these issues, says Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland."At the current time there is no consensus on what reproducibility is or should be.” But just recognizing that is a step forward, he says. “The next step may be identifying what is the problem and to get a consensus.”"

Additionally, the cancer number is deeply flawed for multiple reasons. I find it highly unlikely that cancer research is *less* reproducible than psychology research, as we have a much, much firmer empirical and theoretical basis for cancer research than we do for psychology, and in practice cancer research has led to many highly successful medical therapies, in contrast to psychology.

More specifically, the 10% reproducibility number does not come from a systematic survey of the cancer literature, unlike the psychology study. Rather, the researchers chose a small number of papers "...that described something completely new, such as fresh approaches to targeting cancers or alternative clinical uses for existing therapeutics." That is to say, they chose the most surprising, groundbreaking, exciting papers that could lead directly to new cancer treatments. This will inevitably select for less reproducible papers.

It's definitely worth improving the reproducibility of scientific research but publishing extremely low and unsubstantiated reproducibility estimates around is both unhelpful to that specific goal and will likely lead some readers to completely distrust scientific research, even in fields with a strong track record -for example, vaccinology.

I wonder if you could put something like this in grant applications to get funding for reproductive tech, similar to how anti-aging scientists are sneaking in longevity research through pet longevity.

The pitch would be that you could unlock both standardization and customization for mouse studies, if instead of breeding lines you could create colonies from immortalized cell lines. Under this project, you could justify research into things like gene editing, oogenesis, and artificial wombs.