Solving the Electroporation Bottleneck

Cultivarium, a focused research organization, has built a custom electroporator to engineer non-model organisms at scale.

Science’s most studied organism is, without contest, E. coli. It has prompted at least half a million academic papers, spanning nearly a century of work. And yet a quarter of its genes still do not have an experimentally-determined function, according to a 2019 study.1

If we don’t yet understand the inner workings of a bacterium that scientists have obsessed over for so long, consider how little we are likely to know about everything else.

Scientists have estimated that about one trillion microbial species inhabit the Earth, of which 99.999 percent remain undiscovered.2 Of those that have been cataloged, perhaps a few thousand have been grown in a laboratory. In other words, a vast chasm remains between the microbes one can see under a microscope or locate in the dirt and those we can grow on a petri dish.3 Rounding to the nearest whole number, we have deeply studied zero percent of lifeforms on this planet.

Even if such rounding is hyperbolic, it points to the vast number of possibly useful discoveries still on the table. CRISPR was first found in a salt-loving microbe in Spain. The thermostable DNA polymerase used in modern PCR was discovered in a Yellowstone geyser. Biologists find useful things nearly everywhere they look.

So why don’t we grow and study more organisms in the laboratory?

A few reasons. First, the genetic tools for manipulating more “established” organisms, like E. coli, yeast, and HeLa cells, are quite reliable. Why would a PhD student spend the formative years of her career mixing up liquids to grow an obscure microbe that nobody else has ever heard of? It’s much easier to take a labmate’s vial of cells and get to work straight away on a well-defined research problem.

Another reason is that the combinatorial complexity of biology is vast and difficult to navigate. A typical protein in E. coli is 300 amino acids long, with 20 possible amino acids at each position. The number of possible sequences for this hypothetical protein is thus 20300, more options than there are atoms in the Universe. And that’s just for proteins!4

Similarly, finding the “perfect” ingredients to grow and engineer a new organism requires an equally vast search through combinatorial space. Some microbes need special carbon or nitrogen sources, vitamins, pH levels, and temperatures. Others die if they are exposed to even a hint of oxygen. If our hypothetical PhD student makes a growth media, dips cells into it, and nothing grows, then that failed experiment also returns little useful information; was it the pH or oxygen to blame, or something else?

Finally, even if one manages to grow cells, that is only the beginning for most biology research. We also need to be able to transform, or manipulate DNA inside of cells. After all, scientists figure out how genes work by subtracting them from the genome and then watching what happens to the cell (usually, it dies). Or, to confirm a gene’s role in a phenotype or disease, scientists replace a defective copy with an unmutated version and see if the addition renders a fix.

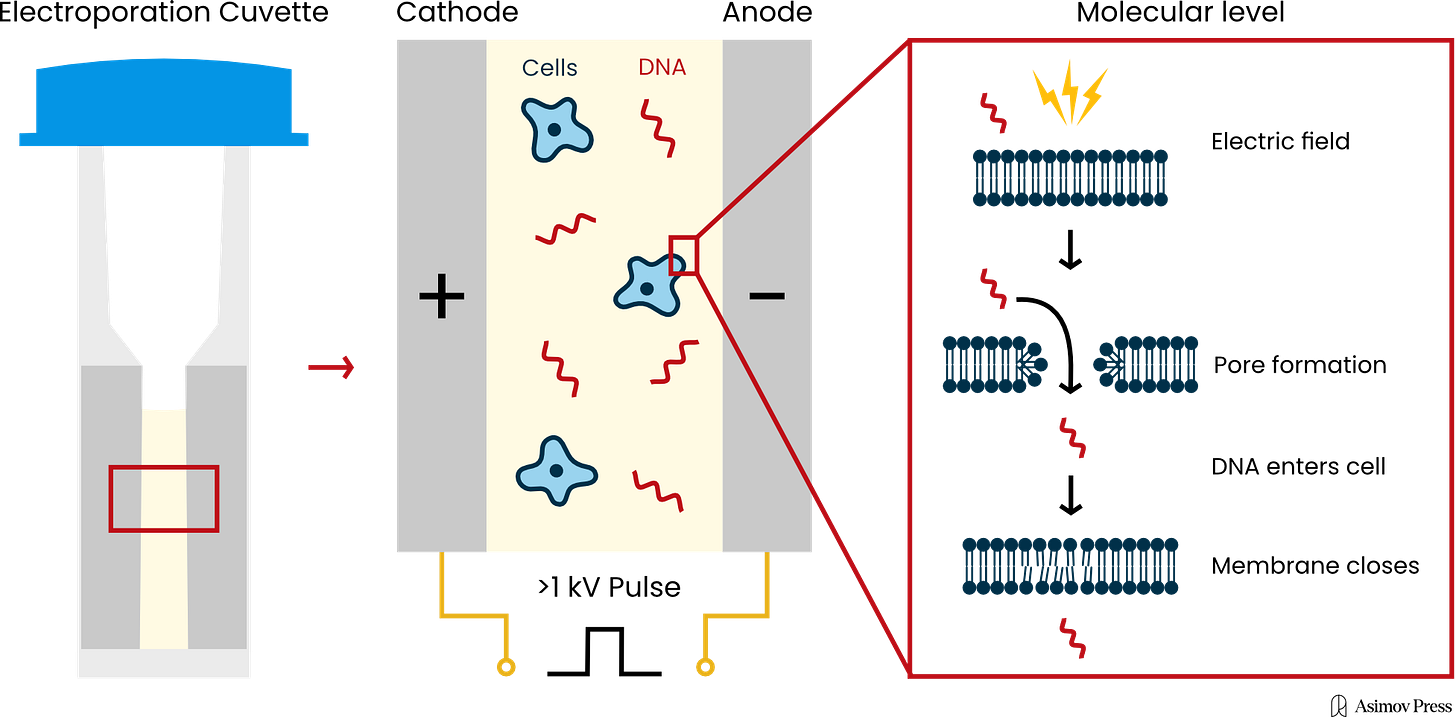

This substitution process only works if scientists can grow and manipulate cells using genetic tools. Both steps are required, and the latter bit — manipulation — usually begins by coaxing cells to take up “foreign” DNA with a technique called electroporation, in which pulses of electricity are used to punch physical holes in a cell through which DNA can sneak inside. But much like finding ideal growth conditions, electroporation has dozens of different parameters spanning many millions of possible combinations, and it’s not often clear which settings will lead to success.

Now it should be clearer why making headway in the biology lab is so difficult. As it so happens, this is exactly the problem that Cultivarium, a nonprofit research organization, is trying to solve. For a recent study, they created a robot that finds working conditions to both grow and engineer non-model microbes. They are giving these growth protocols away for free, in the hopes that others will use them and begin studying a wider range of lifeforms on Earth.

Search Space

In the 1950s, physiologists Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley were studying giant squid axons, which can extend nearly a meter in length and are visible to the naked eye, to understand how electrical signals travel through them. They discovered that electrical signals, rippling along this axon, somehow triggered alternating tides of sodium and potassium moving in or out of neurons. Twenty years later, two scientists at the Weizmann Institute, Eberhard Neumann and Kurt Rosenheck, returned to the Hodgkin-Huxley experiment, wondering if the electrical signals that coax small molecules to move about naturally in the brain could also be used to “program” a cell to release other molecules instead.

Neumann and Rosenheck took lipid vesicles and filled them with proteins and ATP, a type of energy-storing molecule. These vesicles were then wedged between platinum electrodes and zapped. The duo measured which molecules were released from the vesicles using a spectrophotometer, and found that the shocked vesicles dumped ATP while larger proteins remained trapped inside. Their results suggested that membranes became permeable — but were not entirely destroyed — when electrocuted.

In 1982, Neumann probed further, investigating whether he could use electricity to get molecules, such as DNA, into cells. At the time, recombinant DNA was becoming more popular, and dozens of scientists were trying to clone things like the human insulin gene into bacteria. The main methods for doing this were dipping cells in calcium-phosphate (which carries DNA through the membrane via electrostatic charges), microinjection, and viruses. However, none worked reliably across different cell types.

So Neumann, ever the tinkerer, found a tube of frozen mouse fibroblast cells deficient in thymidine kinase, an enzyme required for DNA synthesis. These cells die in HAT medium, a selective liquid that only allows cells with a functional form of this enzyme to survive and grow. First, Neumann created a plasmid carrying the thymidine kinase gene. Next, he performed several trials, trying many different parameters to push this thymidine kinase gene into these deficient cells. He tuned the electrical field strength, pulse durations, temperature, and so on. Finally, he found settings that worked: out of one million cells in the shocked vial, 95 took up the plasmid and grew. The cells that took up the DNA regained the thymidine kinase gene, made the enzyme, and thus survived in HAT. Neumann called his method “electroporation.”5

Today, electroporation remains the most common way to get DNA into cells. The electrical pulses punch tiny, temporary holes in the lipid bilayer, thus allowing charged molecules (like DNA) to slip inside. The method is general, meaning it can work (in theory) on any organism. But it isn’t foolproof, and when it fails entirely, “you often don’t know what went wrong,” says Nili Ostrov, CSO of Cultivarium. “If you get no colonies at all, it could be the plasmid, it could be the conditions, it could be the machine, it could be the buffer, it could be the voltage, and you just don’t know.”

The total space of parameters for a single electroporation experiment is vast. One commercially available electroporator machine, called the BTX Gemini X2, has more than 4.2 million possible settings for voltage, resistance, and capacitance. And this doesn’t even include biological variables, like the buffer in which cells are washed, pH levels, or temperature.

In practice, most scientists today do electroporation using small cuvettes. They wash their cells with some buffer, mix in the DNA, and then put the cuvette into a machine that zaps them. The cells are then transferred into liquid media to “recover” (as they get stressed by the process) after which they might be plated with some selection media, like an antibiotic. If the transformation works, little colonies will appear on the plate after a few hours. If nothing grows, then the scientist has to adjust and try again.

This time-consuming procedure inspired Cultivarium to automate the process. As opposed to a human painstakingly choosing parameters and filling the cuvettes, they built a custom electroporator robot that clamps down onto a 96-well plate and can deliver different electrical pulses to each well. Every well can also have different buffers and DNA concentrations. The machine is controlled through an API, and the team can test 24 different conditions simultaneously in a single run. (The device isn’t yet for sale and Cultivarium has not released the blueprints. They also declined a request to share a photograph of the robot, citing biosecurity concerns.)

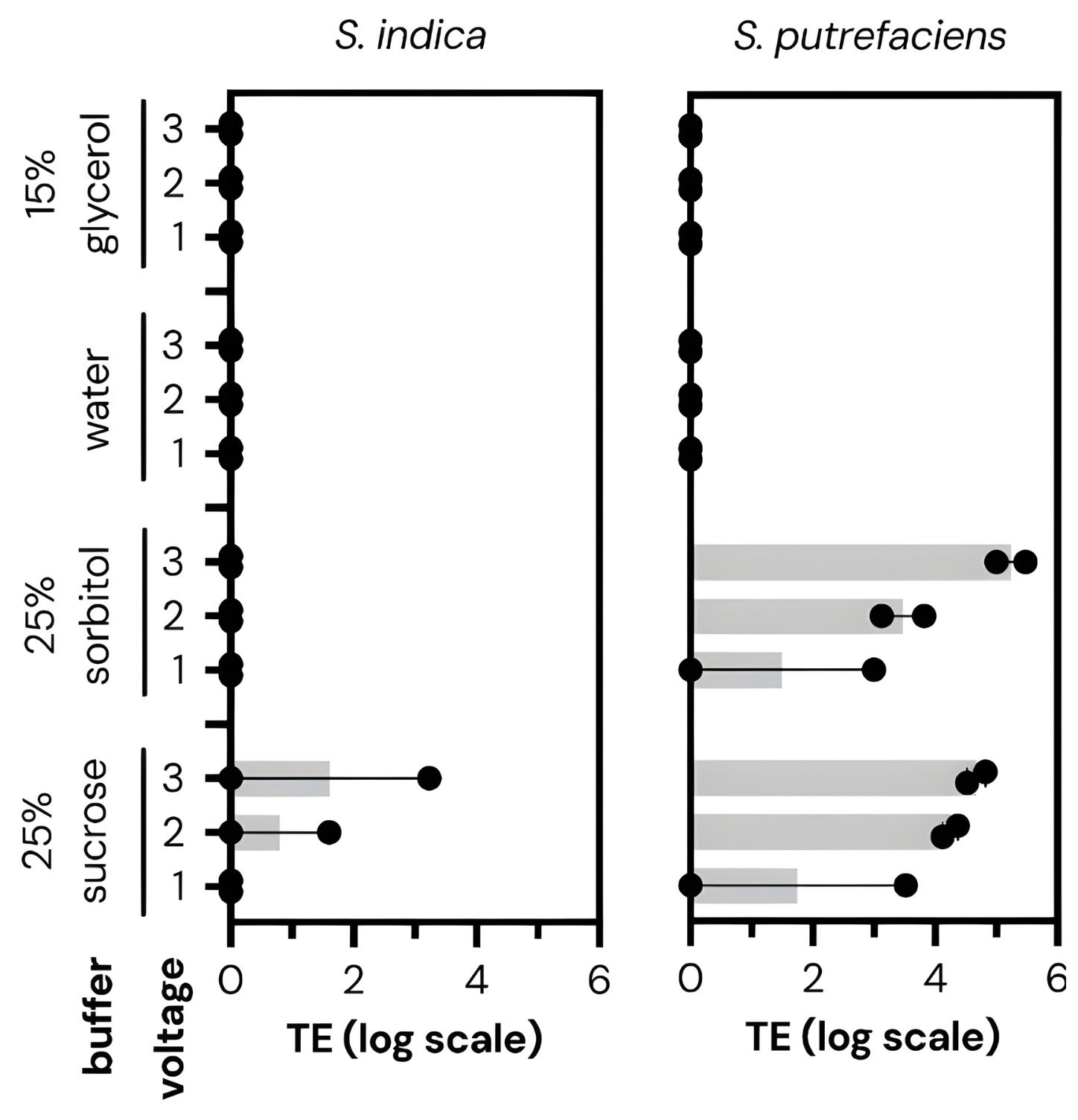

Cultivarium’s first experiments were relatively simple. They took different microbes and seeded them across 24 wells of a microplate. In each well, they varied the wash buffer (sucrose, sorbitol, water, or glycerol), voltage (1, 2, or 3 kV), and waveform (exponential decay or square wave). They shocked all 24 conditions at once, coaxing the cells to take in a plasmid containing an antibiotic-resistance gene. Then, a second robot transferred each well of cells into liquid growth media with the antibiotic. These cells recovered overnight. The next day, a laser measured the optical density, or cloudiness, of each well. Cloudy wells meant bacteria grew; clear wells meant failure.

Cultivarium quickly found electroporation settings that work for many non-model microbes: organisms that nobody had ever transformed before, including Halomonas elongata (used by some companies to make bioplastics) and Piscinibacter sakaiensis (a microbe famous for eating plastic).

Some of the “optimal” parameters were quite surprising. For example, the wash buffer, or liquid used to prepare cells for transformation, had a huge effect on how well the electroporation actually worked. For each of the microbes, one buffer outperformed the others by at least 100-fold. Voltage was also important; while one kilovolt was usually enough to transform cells, increasing this to two or three kilovolts could, in some cases, lead to 1,000-fold improvements. (Higher voltages can also kill the cells, though, so one must tread carefully.)

But electroporation can fail for another reason: even if DNA enters the cell successfully, the plasmid won't survive unless the bacterium recognizes its origin of replication, or the genetic element that instructs the cell to copy the plasmid. To disentangle these two problems, Cultivarium thus combined its electroporation robot with a library of plasmids — each with a different origin of replication — to see which ones worked in each microbe.

They shocked all these plasmids into the microbes at once, grew the survivors, and then sequenced whatever grew to identify the working plasmids. Using this approach, they were able to transform two species of ocean-dwelling microbes, called Shewanella, that nobody had managed to work with before.

Finally, the team developed an active learning framework, in which they let a Bayesian optimizer choose which settings to try in each experiment. To begin, Cultivarium’s robot runs an initial round of experiments, testing 176 different conditions spread across the parameter space. The results — like which conditions yielded colonies, and how many colonies — are fed into the algorithm, which then suggests the next conditions.

“We take these results and then ask the model to suggest which ones we should optimize around,” says Stephanie Brumwell, lead author on the paper. “The goal is to let the model suggest what we cannot rationalize.”

They used this Bayesian optimizer on Cupriavidus necator, a bacterium that converts carbon dioxide from the air into a biodegradable plastic, called PHA. Over three cycles of active learning, the model found transformation efficiencies 8.6-fold higher than anything previously described in the literature.

Untapped Nature

I’ve profiled Cultivarium before, and my doing so again is a first. But their work feels deeply important because it is by tinkering with non-model organisms that biotechnologists have, historically, found the most useful tools.

Taq polymerase and CRISPR were both discovered in unusual organisms, as I said before. Green fluorescent protein was first isolated from jellyfish caught off the coast of Friday Harbor, Washington. Luciferase came from the North American firefly. Rapamycin, an immunosuppressant used in organ transplants, came from Easter Island soil microbes. Many more useful discoveries are surely awaiting, if only we could grow the many lifeforms that nobody has yet studied in any meaningful way.

Consider a scenario in which scientists discover a microbe that eats plastics, like Piscinibacter sakaiensis. They’d like to study this microbe in the laboratory. They begin by sequencing the cells’ genome, quickly spotting the stretch of DNA encoding the plastic-degrading enzymes.

From here, the scientists could try and synthesize the plastic-eating genes and put them into another microbe, like E. coli, that is easier to work with. This is basically the logic of metagenomics: sequence environmental samples, identify interesting genes computationally, and express them in a more cooperative host. This approach was recently used to discover Bridge recombinases, a new type of genome-editing tool.

But this doesn't always work. Many fascinating biochemical mechanisms, especially those involving multiple genes, can only be understood in context; they stop working entirely when transplanted into another cell.

To deeply study a biological mechanism, then, the only option is often to work with the native host, complete with its evolutionary baggage. So the scientists take some broth off the shelf and dip the plastic-eating cells in, yet nothing grows. So they try a different medium, and another, again and again. They tweak the temperature, pH, and oxygen levels and then — at last! — the cells begin to grow.

Now they want to actually use this organism to do things. Perhaps they want to delete a gene to prove its link to plastic degradation. Or they want to overexpress an enzyme to see if they can speed up its plastic-munching. For these experiments, they need to get foreign DNA into the cell. They need electroporation — or something like it — to work.

All of this tinkering takes time.

And this, at last, is why I think Cultivarium’s robot is such a big deal. It’s not only about scaling up plastic-eating microbes, but about scaling anything else, too! This work makes it feasible for scientists to work much more rapidly with a vastly larger number of organisms, which I would argue is one of the most fundamental bottlenecks in biology and which, when solved, will fling scientific discovery into unimaginable directions.

Niko McCarty is a founding editor of Asimov Press.

Cite: McCarty, N. “Solving the Electroporation Bottleneck.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/28hw-48hq

Specifically, the researchers identified 1,600 out of 4,623 unique genes — what they termed the “y-ome” — that lack direct, experimental evidence of a function. I’ve not seen an updated count, but presumably the gap has closed quite a bit over the last six years.

Researchers made this estimate using mathematical scaling laws; with a database of 5.6 million species from 35,000 locations, they extrapolated to predict the abundance and diversity of organisms elsewhere.

This has frustrated microbiologists for decades, actually. In 1985, James T. Staley and Allan Konopka noted that they were only able to recover about one percent of bacteria from a sample; they dubbed this the “Great Plate Count Anomaly.”

Admittedly, if we envision the total space of “protein possibilities” as a handkerchief, the protein sequences likely to yield a functional, folded protein would probably only make up a few threads in that fabric.

8 kV/cm field strength, 5 microsecond pulse, 3 pulses with 3 seconds between pulses, 20 °C temperature, and no magnesium chloride!