This is our final article in Issue 08, and also marks the second anniversary of Asimov Press! We’re grateful that we get to publish these stories. See you in the New Year :)

By Michael DePeau-Wilson

For millennia, our ancestors sought every imaginable cure for the common cold, from ancient Greeks who boiled hyssop with figs, water, honey, and rue, to the 15th-century English, who made a remedy by brewing “stale ale, mustard seeds, and ground nutmeg.”

Despite such efforts, generation after generation continued to suffer from nasal congestion without any effective, scientifically proven alternatives.

This began to change around the turn of the 20th century with the rise of industrial chemistry. Whereas ancient people used boiled herbs, ground botanicals, and bloodletting to relieve cold symptoms, improved chemical synthesis methods allowed for the creation of a much neater and more precise “commodity-based medicine,” characterized by pills and powders.

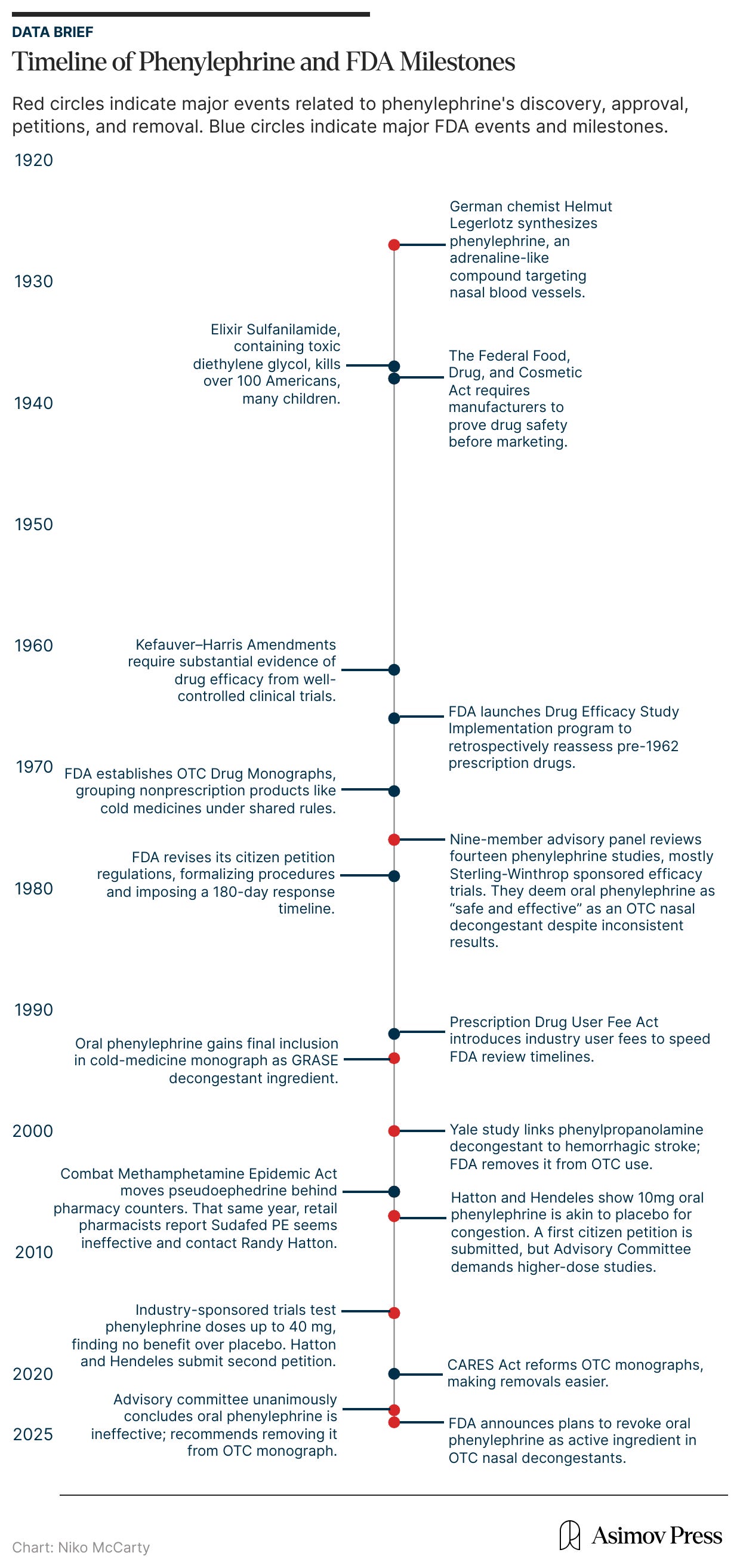

Oral phenylephrine was one such chemical treatment. It was first synthesized in 1927 by the German chemist Helmut Legerlotz, who sought to replicate the hormone epinephrine (more commonly known as adrenaline), which stimulates receptors connected to blood vessels, causing them to narrow. The formulation that would become phenylephrine was closely related to this hormone and was purported to affect blood vessels in the nose, shrinking swollen mucus membranes and opening the airway.

By 1938, pharmaceutical products company Frederick Stearns & Company had begun to sell phenylephrine to millions of Americans under the brand name Neo-Synephrine. It was initially sold as a liquid solution, taken orally or intranasally, for the treatment of “the common cold.” In some cases, physicians also used phenylephrine to manage hypotension caused by neuraxial anesthesia during pregnancy or as an eye treatment. And by the 1950s, it was being offered in tablet form, similar to modern formulations.

In the early 1970s, however, the FDA re-examined phenylephrine as part of a massive effort to review all older prescription drugs — more than 3,400 that had been approved based only on safety data between 1938 and 1962 — for proof of effectiveness, a process instated after the thalidomide crisis. A panel of experts evaluated fourteen studies of oral phenylephrine, most of which had been funded by its manufacturer, Sterling-Winthrop. Only a few of those studies had shown any benefit, and several others found the drug performed no better than a placebo in relieving nasal congestion.

Despite this tepid evidence for phenylephrine’s efficacy, however, the panel deemed the drug “safe and effective,” and it remained on the market for another 50 years. It was not until November 2024 that the FDA announced plans to revoke approval of oral phenylephrine as an active ingredient in over-the-counter (OTC) cold medications used for nasal decongestion.

But why did it take half a century for the FDA to pull an ineffective drug from the market?

While one could read the sluggish pace of the FDA as an exercise in caution, details of this saga reveal other explanations for the agency’s often slow drug removal process; most notably, its interdependence on industry-sponsored data and funding for drug reviews and its tendency to quickly act on safety concerns, while dragging its feet when it comes to those of efficacy.

The problems this dynamic produces are manifold. First, even though phenylephrine didn’t directly cause any deaths, every drug carries some level of risk for side effects, and this risk–benefit equation collapses when a drug is not effective.1 Second, common generic drugs represent billions in revenue for pharmaceutical companies (and millions in fees paid to the FDA), even when their therapeutic worth is dubious. When such drugs continue to generate large profits without offering substantive benefits, they linger on the market longer than they should. And finally, without sufficient resources and scrutiny devoted to generic and monograph drug products after their initial approval, drugs like phenylephrine often remain widely used long after their efficacy has been discredited.

To understand the story of oral phenylephrine and why its removal took 50 years, we must first examine the forces that shaped the FDA itself.

The Origins of Drug Regulation

Oral phenylephrine emerged during a highly productive period in medicine. In 1922, Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old boy with diabetes, became the first person to be treated with insulin injections. In 1928, Sir Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in mold growing on one of his bacterial samples. And in 1937, Max Theiler, a South African-American physician, developed the first vaccine for Yellow Fever.2 As the scientific breakthroughs quickened, legislators struggled to keep pace.3

A 1937 tragedy finally impelled the federal government to impose regulations on the growing drug market. A Tennessee company, S. E. Massengill, had released a medicine called Elixir Sulfanilamide, a raspberry-flavored liquid version of an antibiotic (sulfa) used to treat strep throat and other infections. To dissolve the medicine, the company’s chemists had mixed it with diethylene glycol, a toxic chemical used in antifreeze. They did not run any safety studies on this updated mixture, as none were required at the time.

Within weeks, this Elixir syrup had caused the death of more than a hundred people across fifteen states, many of them children. The disaster provoked national outrage and congressional hearings; newspapers printed photographs of the victims, and the elixir was pilloried on the Senate floor. This anger spurred the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, which, for the first time, required manufacturers to prove that their products were safe before sale. Oral phenylephrine entered the market that very year, riding the tide of modern, chemistry-based medicine and the first wave of genuine pharmaceutical oversight in American history.

After the 1938 Act, however, it would take another 24 years before the government would introduce requirements for drug efficacy. This time, the policy changes were driven by a narrowly averted disaster.

In 1961, Chemie Grünenthal, a German-based company, asked for U.S. approval to sell thalidomide, a sedative that physicians abroad were prescribing to ease morning sickness in pregnancy. Its American partner, Richardson-Merrell, submitted a file typical of the pre-1962 era: brief animal-toxicity studies, physician testimonials from Europe, and anecdotal “clinical experience” reports. There were, however, no controlled human trials, no data on how the drug was metabolized, and no tests of its effects on fetal development.

The FDA reviewer assigned to the case, Frances Oldham Kelsey, vehemently interrogated Richardson-Merrell’s claims. Reports from Europe had already described cases of peripheral neuritis (nerve damage and tingling) in patients taking thalidomide, findings the company had not disclosed.4 Kelsey also noted that the safety file contained nothing addressing use in pregnancy, even though the drug was aimed at pregnant women.

Kelsey refused the application for thalidomide, asking for more evidence. Shortly after, she saw a case report published in the British Medical Journal linking thalidomide to catastrophic birth defects. Her vigilance mostly kept the drug away from Americans (although by 1962, unregulated trials for the drug were believed to have exposed roughly 20,000 Americans to thalidomide). Abroad, where the drug had already been approved, more than 10,000 children were born with limb deformities.

The thalidomide disaster sparked a public outcry for stricter regulations in the FDA’s drug review process. So in 1962, Congress passed the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. For the first time, these amendments required pharmaceutical companies to prove both the safety and efficacy of new drugs through well-controlled clinical trials before FDA approval. Pharmaceutical companies seeking to release new products were required to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, according to the New Drug Application (NDA) process.

Importantly, the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments were also retrospective. That is, the FDA was required to go back and assess or reassess the thousands of drugs, including prescription and OTC drugs, that had long been on the market. To manage the enormous workload, the agency created the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation program in 1966, partnering with the National Academy of Sciences to review every prescription drug approved since 1938.

Because OTC drugs were considered safer, however, they were given a lower priority than prescription medications and would be reviewed last. By 1972, the FDA still had only examined a fraction of OTC products already on the U.S. market. To expedite this monumental task, the agency developed a new process for assessing and approving large groups of OTC drugs using an internal rulemaking protocol. The new protocol created the OTC Drug Monographs program, which would manage the review of up to half a million OTC drugs and was one of the largest and most complex regulatory undertakings in the agency’s history.

This process allowed the agency to review an entire category of drugs for a specific type of drug product, such as cold medication. The ingredients and instructions for use, like dosage and warnings deemed acceptable for each specific product type, were added to an approved list, called a monograph. It was essentially a shortcut, for even as its budget grew, the FDA simply did not have the resources to review each formerly approved drug individually.

With the OTC Drug Monograph program, a pharmaceutical company looking to sell an OTC drug didn’t need to submit its own application for FDA approval. Instead, it only needed to ensure that its product fell within the conditions laid out in the relevant OTC monograph — using an ingredient that the FDA has already deemed generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE), at the approved strength (e.g. 10mg), dosage form (e.g. oral tablet), and labeling. Once those standards had been met, the company could market the product immediately, as compliance with the monograph itself serves as legal authorization to sell it. It is only when a product falls outside an existing monograph — say, because of a new active ingredient, higher dose, or new indication — that a manufacturer has to go through the more rigorous NDA process, either as a generic or a new brand-name drug product.

Around the time that these two pathways to approval were forming, the FDA budget also doubled, and it gained regulatory power over a wider swath of the medical industry. By 1976, the agency added four new bureaus overseeing biologics, radiological health, medical devices, and toxicological research. The FDA hardly resembled the agency that had given oral phenylephrine its safety approval 34 years before. But its monograph process and other efforts to streamline drug review processes would have a profound influence on its future.

Structural Flaws

Oral phenylephrine was reviewed under the Cold, Cough, Allergy, Bronchodilator, and Antiasthmatic (CCABA) OTC monograph. From 1972 to 1976, a nine-member advisory panel reviewed data from 14 studies conducted between 1959 and 1975. Of those 14 studies, 12 assessed phenylephrine’s efficacy and seven showed positive results. But the vast majority of those studies also came from a single sponsor (the company seeking approval) — Sterling-Winthrop Research Institute, a company heavily invested in phenylephrine’s success.5

The FDA’s dependence on company-funded research is not new. It dates back to the original structure of its drug review process, which relies on the sponsor to provide evidence that a product is safe and effective. While it makes sense that the applicant should fund this research, it is perhaps too much to expect that the same company would be unbiased enough to produce reasons why the product should not be approved.

Sterling-Winthrop had purchased the original manufacturer of oral phenylephrine products, Frederick Stearns & Company, in the 1940s and was still producing Neo-Synephrine when the committee met. Thus, of the seven studies that showed positive efficacy results for oral phenylephrine, six had been conducted by Sterling-Winthrop.

In 1976, after years of review, the advisory panel determined that oral phenylephrine was “safe and effective as an oral and as a topical nasal decongestant for OTC use.” The agency’s commissioner accepted this finding and eventually granted phenylephrine tentative approval in 1985. Despite this approval, the 1985 advisory committee admitted the data was “not strongly indicative of efficacy” for oral phenylephrine, according to the FDA briefing documents released in 2023. Still, by 1994, oral phenylephrine had been granted final inclusion in the cold-medicine monograph.6

Oral phenylephrine’s inclusion (despite lukewarm evidence on efficacy) was made possible by a couple key elements within the review process. First, oral phenylephrine was being considered alongside dozens of other drugs within its category (and thousands of generic drugs in total), which stretched the capacity of the reviewers. And second, the studies presented to the original advisory panel were not subjected to any third-party review.

Today, the FDA has evolved its drug review processes to include more requirements — such as publishing guidelines for optimal drug study designs, overseeing study sites and conduct, and requiring preapproval for study protocols. But the agency still relies heavily on industry-sponsored evidence, without requiring any third-party review of those outcomes, including from its Advisory Committees. And in the decades since phenylephrine’s approval, Congress has further intertwined the FDA’s budget with the pharmaceutical companies it seeks to regulate through “user fee” programs.

These fees are mandatory payments that pharmaceutical companies make to the FDA to help fund the agency’s drug review and oversight activities. Established by Congress through a series of laws beginning with the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992, they were meant to speed up drug approvals by giving the FDA resources to hire staff and meet review deadlines.

Companies pay fees both when submitting new drug applications — roughly $4.3 million per application in 2025 — and annually to maintain products that have already been approved. Similar fee programs exist for generic medicines under the Generic Drug User Fee Act (GDUFA), and for over-the-counter monograph drugs, and those payments are used to support applications, facility inspections, and drug product reviews. By 2022, user fees represented 46 percent of the agency’s total budget, or nearly $3 billion.

Taken together, the monograph rule of 1972 and the PDUFA of 1992 propelled the FDA toward an era of shorter review periods and faster drug approvals. Further efforts to expedite approvals came in 1997 when the U.S. Congress passed the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act, which codified the agency’s accelerated approval program and allowed the agency to approve drugs based on surrogate endpoints while waiting for confirmatory clinical trials. (An example of surrogate data would be evidence of a cancer drug’s reducing the size of a tumor in a patient. While it’s not hard to see why this measure is promising, it does not demonstrate how well the drug would treat a patient’s overall condition, or for how long.)

The median number of generic drugs approved each year increased from 284 between 1985 and 2012 (when the GDUFA went into effect) to 588 between 2013 and 2018. For New Drug Applications, the average number of annual approvals increased from 34 in the 1990s to 42 in the mid-2010s.

There are also signs that the agency would like to shorten approval times further still. In June 2025, Commissioner Marty Makary announced plans to reduce the average review period for certain drugs deemed in “the health interests of Americans” from an average of 10 months to just one.7

While faster approvals are a good thing in that they speed up access to potentially lifesaving treatments, they can also, on occasion, mean drugs with poor efficacy go overlooked, especially if the FDA is relying on more surrogate endpoints and less thoroughly reviewed data.

In one example, the FDA granted Roche an accelerated approval in March 2019 to market the monoclonal antibody atezolizumab in combination with a chemotherapy drug for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. The decision was based on early results from a phase 3 clinical trial on atezolizumab but was also made contingent on the full results of a separate phase 3 trial. When the results of the second trial were made available in 2021, they proved disappointing, resulting in the FDA ordering its removal from the market.8

Notably, this removal illustrated a rare example of the accelerated system working properly, but there are many other occasions when a company fails to conduct the confirmatory trial, allowing ineffective drugs to remain on the market. This issue becomes more concerning when factoring in the number of drugs that never meet those confirmatory trial standards at all. In fact, between 2009 and 2022, nearly a quarter of approved cancer drugs were withdrawn due to a lack of benefit over standard of care, according to a 2023 JAMA research letter.

Additionally, more than half of newly approved pharmaceutical products between 1980 and 2022 secured approval by using at least one of the FDA’s expedited designations, according to a 2024 Nature study. The study also notes that of the drugs submitted and approved via accelerated means since 1992, 11.4 percent were based on surrogate endpoints. Indeed, the authors of the 2024 Nature study concluded that “the approval of new drugs without reliable confirmatory evidence of their safety and effectiveness transfers the burden of the decision about the risk-benefit trade-off to clinicians and patients.”

Trying (and Failing) to Pull a Drug

After oral phenylephrine was added to the OTC monograph in the 1970s, it receded quietly back into the medicine cabinets of Americans for decades. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, consumers around the U.S. had plenty of choices to alleviate their cold symptoms, including the decongestant drugs phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine, sold as Sudafed.

However, this uneventful period did not last. Starting in 2000, the FDA became aware of concerning safety data related to phenylpropanolamine.9 A group of Yale researchers found a link between the decongestant and increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women. The FDA acted swiftly, removing it from the OTC monograph and asking drug manufacturers to reformulate any products containing it.

Then, in 2005, political pressure forced Congress to take action by implementing additional safety measures regarding pseudoephedrine, without input from the FDA. At the time, the U.S. was at the height of the methamphetamine epidemic, and pseudoephedrine was an ingredient commonly used to cook meth. Congress responded by passing the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005, which removed pseudoephedrine from the OTC monograph and required it to be sold behind the counter.

In a span of just five years, oral phenylephrine went from being one cold medicine on a crowded pharmacy shelf to the primary ingredient in many OTC decongestants. While it was part of the same OTC monograph approval process as phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine did not raise any safety concerns (and it was not used to cook meth.) Its approval status remained unchanged, and common cold medicines, like Sudafed, were reformulated with it, becoming “Sudafed PE.”

As pharmacists and consumers turned to these reformulated drugs, however, they noticed a difference from the old pseudoephedrine-based products; namely, that they were not as effective at reducing cold symptoms. This moment marked the beginning of the fall of oral phenylephrine.

In 2005, retail pharmacists across the country began hearing from patients that Sudafed PE did not work like the “old” Sudafed. When Randy C. Hatton, pharmacist at the University of Florida, caught wind of this, he began looking for answers.

He soon came across data, published by a pharmacist named Leslie Hendeles in 1993, showing that oral phenylephrine was not as effective as its recently dethroned counterparts, phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine. Concerned about the drug’s approval, given the poor evidence for its efficacy, Hatton and Hendeles began to collaborate. Since several studies from the 1960s and 1970s remained unpublished, they had to submit a Freedom of Information Act request for the FDA’s data on the drug’s initial approval before conducting a meta-analysis of the original research.

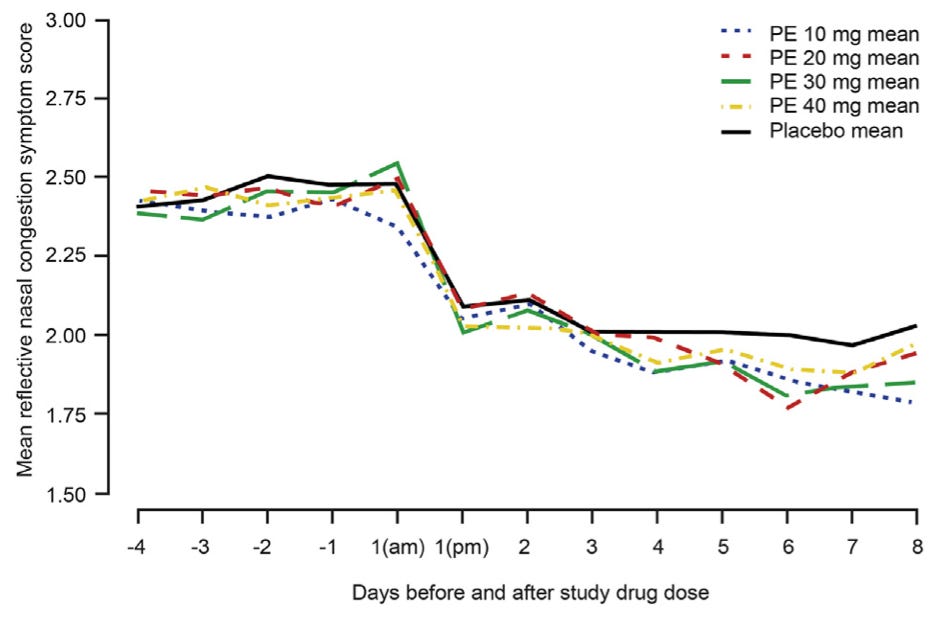

In 2007, the duo published a systematic review and meta-analysis that pooled data from randomized, placebo-controlled trials. They found that a 10 milligram dose of oral phenylephrine — the same dose recommended by the drug’s manufacturer — did not significantly reduce nasal airway resistance compared to placebo, and patient-reported symptom relief was inconsistent. Hatton and Hendeles also discovered that most of the positive studies the original 1976 panel had relied on were unpublished, manufacturer-sponsored, and lacked adequate controls.

To get the FDA to reconsider its approval of oral phenylephrine, Hatton and Hendeles filed a citizen petition. These petitions were made possible by an amendment made to the FDA in the 1970s, which allowed members of the public to request that the FDA “issue, amend, or revoke a regulation.”

Afterward, Hatton noted that the agency “somewhat begrudgingly convened a Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee meeting to review the compound’s effectiveness.” In that meeting, Hatton and Hendeles presented their findings that the standard 10 milligram oral dose of phenylephrine showed little or no consistent efficacy compared to placebo in reducing nasal congestion. They urged the FDA to revise its dosing criteria and go further: revoke OTC approval for children under age 12, citing the lack of safety or efficacy data for that age group (and no supporting pediatric trials).

Hatton and Hendeles also requested that the agency authorize and review higher doses — up to 25 milligrams every four hours — to test whether a stronger dose could overcome the drug’s poor oral absorption, which earlier data suggested might be a limiting factor.

In their 2007 petition, Hatton and Hendeles argued that the 1976 OTC panel had ignored dose-response evidence in selecting the 10 milligram dose. For example, the duo pointed out one study (not reviewed by the original panel) where a 25 milligram dose produced a statistically significant reduction in nasal airway resistance compared to 10-milligram or 15-milligram doses. Hatton and Hendeles also analyzed the evidence the 1976 panel cited and determined that only four studies truly supported phenylephrine’s effectiveness, while seven studies showed no benefit over placebo. “In our view,” they wrote, “the panel reached a specious conclusion that was not based on a systematic review of the available data.”10

Although their petition prompted a formal review, it was only the start of a long process. In December 2007, the FDA’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee reviewed the Hatton-Hendeles petition, hearing arguments from both researchers and industry representatives who defended phenylephrine’s 10-milligram dose.

The committee voted twice. It found, 11 to 1, that existing data suggested the 10-milligram dose might be effective, and 9 to 3 that more research was needed on higher doses. After the meeting, Schering-Plough, a subsidiary of Merck that presented data during the meeting, and McNeil Consumer Healthcare, the manufacturer of Sudafed PE, began testing those higher doses. Four clinical trials followed, the last two appearing in 2015.

That year, Hatton and Hendeles filed a second petition summarizing the new results, which showed that even quadrupling the dose to 40 milligrams produced no greater relief than placebo. Their first petition had asked the FDA to revoke approval for children under 12 and to re-evaluate dosing; this time, they demanded the FDA completely remove oral phenylephrine from over-the-counter decongestants.

They may have expected a swift response, as in 2007, but none came. Eight years later, in September 2023, the FDA finally reconvened its advisory committee; this time to decide whether to strike oral phenylephrine from the OTC monograph entirely.

This long wait is typical of the FDA’s citizen petition process. Petitioners must gather and analyze data, prepare legal filings, and present them for review, only often to be told that more evidence is needed. A 2016 rule requires the FDA to respond to petitions within 180 days, but the agency rarely meets that deadline. Indeed, a 2023 Health Law Advisor report found that many petitions, especially those submitted to the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, have gone unanswered for years or decades.

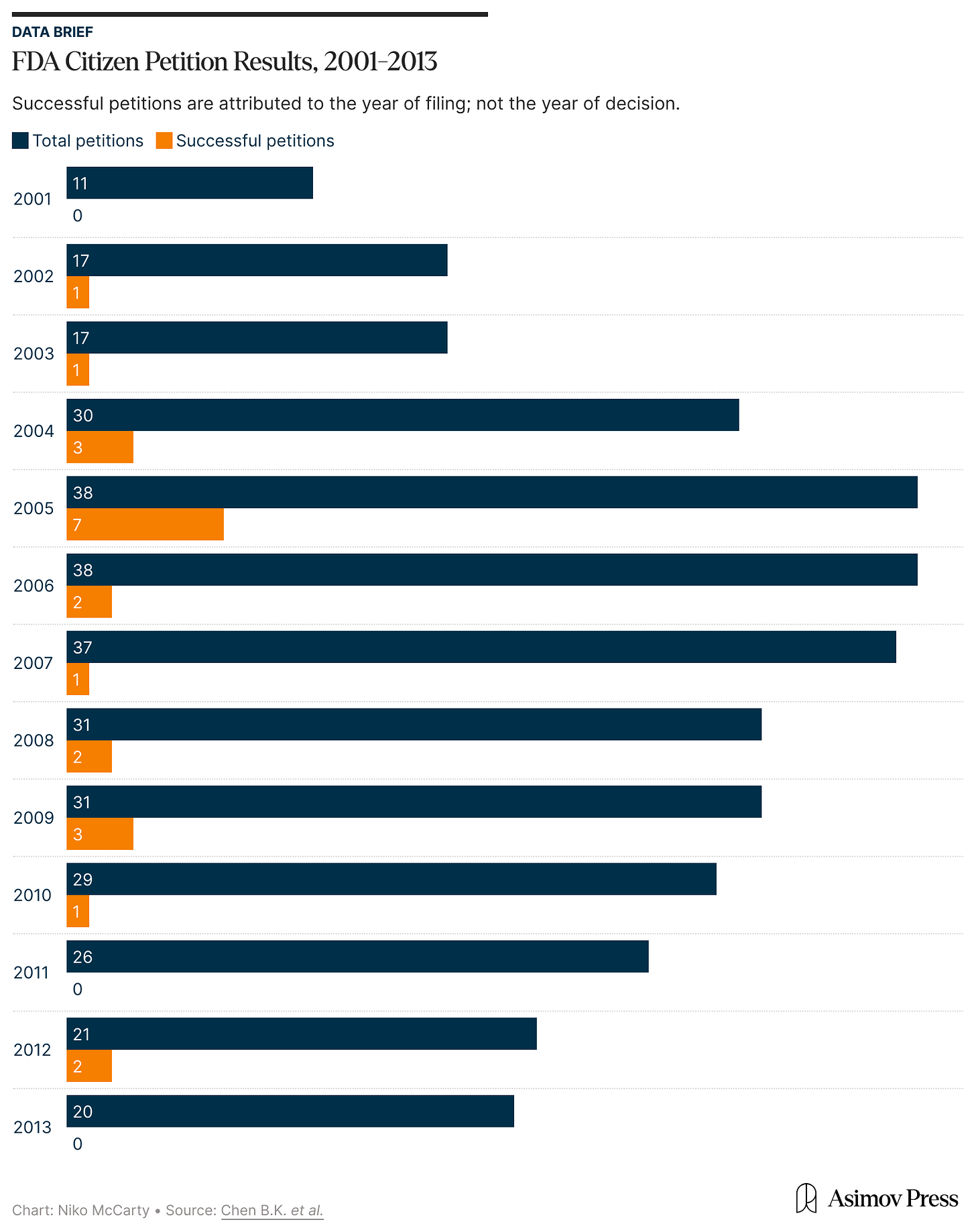

When the agency does respond, the results are not usually good for petitioners. Between 2008 and 2023, the FDA resolved 265 petitions: most were denied or withdrawn, 58 were partly granted, and only 10 succeeded, meaning the FDA agreed to make changes requested in those petitions.

Citizen petitions were devised to serve as a check on the agency’s mistakes, allowing outside scientists to challenge medicines that no longer meet modern standards of efficacy. While this particular petition eventually succeeded, the travails faced by Hatton and Hendeles raise the question of whether citizen petitions, as a mechanism by which drugs are challenged, are effective. Other than in the case of oral phenylephrine, only one other petition has helped prompt the FDA to remove an ineffective or unsafe drug since 2001.11

In fact, an independent analysis of the FDA’s response to citizen petitions found the agency denied “87.3 percent of petitions by individuals, not-for-profit organizations and advocacy groups, and other governmental agencies” between 2001 and 2013. The authors noted that even many partially granted petitions were effectively denials due to the agency’s refusal to act on the request. Following their review of nearly 2,000 petitions, they concluded that “citizen petitions filed by ‘ordinary’ citizens are rarely successful.”

Approvals Take Years, Removals Take Decades

From 2007 to 2015, Hatton and Hendeles had presented the FDA with several pieces of corroborating evidence that oral phenylephrine didn’t work. By the time the advisory committee reconvened in 2023, the decision seemed inevitable. One panelist even said further debate would be “beating a dead horse.”

Forty-seven years after phenylephrine’s first approval, the committee voted unanimously that the drug was ineffective. In its briefing documents, the FDA panel offered little explanation for the long delay, citing only that phenylephrine had no known safety issues and that removing it would have “a significant impact on industry.” (At the time of its removal, roughly half of U.S. households had purchased phenylephrine products over the previous year, amounting to $1.8 billion in sales.) Given this hit to the market, it’s perhaps unsurprising that this process was so protracted. Phenylephrine products were tremendously lucrative, and although they weren’t helping people, they weren’t harming them either.12

To illustrate this perspective, the chair of the 2007 nonprescription drugs advisory committee, Dr. Mary Tinetti, posited that efforts to remove the drug from the market were “ignoring the fact that millions and millions of people are using [oral phenylephrine products] and are voting with their pocketbook.” She added that “clearly, they feel that [oral phenylephrine products] are effective or they wouldn’t be using them.”13

The more charitable take, however, is not that the FDA is willing to overlook efficacy in favor of maintaining market stability, but simply that once drugs have been approved, it is onerous and expensive to revisit their qualifications. In fact, the agency was provided some reprieve from this predicament during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic when Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020. The CARES Act reformed the OTC monograph process to make it “less burdensome on the agency to update and create new monographs.”

It’s likely not a coincidence that the agency finally reconvened the advisory committee to review oral phenylephrine shortly after the CARES Act went into effect.

The challenge ahead, then, is to make such reforms and corrections happen faster. And not only faster, but earlier in the process, as rapid approval and subsequent removal of those treatments would be destabilizing. What we need is not merely speed in both directions, but better vetting upfront and a smarter, swifter way to correct course when evidence changes.

This, of course, is no easy task. Every new law or rule change within the FDA joins the intricate scaffold propping up the weight of the entire U.S. drug market.

Lately, this scaffolding has come under enormous pressure from changes within the FDA, driven almost entirely by political ideologies. If the agency emerges from this moment intact, it will once again be time to consider the necessity of these changes to drug approvals and monitoring. However, if the agency cracks under the political pressures, future FDA leadership and the American people will have to find new ways to build this storied agency from the ground up all over again.

Even considering the precarity of the present moment, the FDA has been largely effective in balancing its commitments to both industry and consumers. When it comes to safety concerns, the agency has also been remarkably responsive to public pressure over the years, most notably in 1938 and in the 1960s. Its ability to adapt and improve has led to decades of relative stability while continuing to encourage drug innovation.

An example of this is the agency’s recent development of a proposed guidance statement outlining several rule changes to the accelerated approval process based on the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023. One of those changes requires drug companies to submit plans for confirmatory clinical trials before gaining approval, instead of waiting until after the approval to initiate trial planning. The guidance statement also requires drug companies to update the FDA on research progress every six months.

More crucially, this proposed statement also presented a new expedited withdrawal process for drugs approved through the accelerated pathway, paving the way to remove drugs that failed to match their nonclinical endpoints in clinical trials. Though a promising acknowledgment that the agency is aiming to respond more quickly to shortcomings, the changes have yet to be formalized.

Still, as the market for new brand-name drugs grows, the FDA needs to consider the downstream effects — 10, 20, or even 50 years in the future — for generic and OTC drug products. If the quality of new (and hastily approved) drugs wanes while they continue to stay on the market, it could lead to a glut of ineffective drugs clogging shelves and frustrating consumers in the not-so-distant future.

If the oral phenylephrine saga has shown us anything, it’s exactly how hard it can be to work backward. The agency shouldn’t focus all of its energy and resources on approvals if the process risks grandfathering in new drugs with comparatively fewer (and far more onerous) pathways to retirement. Instead, the agency needs to find pathways to remove ineffective drugs just as quickly and effortlessly as those that allow them to enter the market in the first place.

Michael DePeau-Wilson is a health journalist whose work explores technology, medicine, clinical practice, and human behavior. Over a decade of professional reporting, he has covered a variety of medical specialties for national outlets including MedPage Today, Medscape, ABC News, and Anesthesiology News. His recent reporting on the rise of AI in healthcare and FDA regulatory updates reflects his broader focus on what happens when scientific progress meets the realities of clinical practice and patient care.

Thanks to Ben Gordon for feedback on this draft and Adam Kroetsch for providing an FDA insider perspective. Header Image by Ella-Watkins-Dulaney. Inspired by Leonard Karsakov’s 1941 U.S. Public Health Poster.

Cite: DePeau-Wilson, M. “Why the FDA Is Slow to Remove Drugs.” Asimov Press (2025). https://doi.org/10.62211/52fj-96ty

Similarly, every drug presents the risk for harmful drug-drug interactions.

This vaccine is estimated to have saved millions of lives and earned Theiler a Nobel Prize in 1951.

Americans gained protection from contamination through the 1906 law, but had to wait another 22 years for safety protections. These were critical advances in consumer protections related to drugs, at a time when pharmaceuticals were becoming a burgeoning industry. Still, by the late 1920s, Americans could reasonably expect their drugs to be safe, unlikely to cause crippling unintended side effects, and untainted by dangerous ingredients, such as alcohol or cocaine.

Kelsey challenged a company executive about its not having disclosed evidence of peripheral neuritis related to the drug’s use in England.

In the 2023 briefing documents for the advisory committee, the FDA explained the other two studies contained details related to effectiveness, but “provided no useful efficacy information” related to oral phenylephrine as a decongestant.

Notably, phenylephrine also gained FDA approval for a second condition in 1954. In hospitals, it is used intravenously to elevate dangerously low blood pressure in adults. It also became available as a topical solution to treat hemorrhoids and as an ophthalmic solution to dilate pupils for eye exams or surgery.

It is worth noting that the FDA gave Kelsey 60 days to review thalidomide in 1961, an era with far less regulatory rigor.

In fact, ineffective cancer and psychiatric drugs often remain on the market for years after their failures are known. One study found that ineffective cancer drugs typically spend 46 months on the market after approval.

Phenylpropanolamine is lipid-soluble and readily crosses through cell membranes. Phenylephrine, on the other hand, carries an extra hydroxyl group that makes it more polar and rapidly metabolized in the gut, preventing it from reaching high concentrations in the bloodstream.

Notably, Hatton and Hendeles specifically drew attention to a single laboratory, Elizabeth Biochemical, which conducted 5 of the 12 studies reviewed by the original panel. They asserted that this one lab “appeared to drive the majority of the positive results, and therefore the Panel’s recommendations.” After a review of the data, the FDA found that one of the studies conducted by Elizabeth Biochemical appeared to have concerning data-integrity issues, while another study had methodological and statistical issues which made the inclusion of both studies “highly problematic.”

Filed in 2002 by the non-profit consumer rights advocacy group Public Citizen, the petition called for the removal of sibutramine, a weight loss drug, based on earlier clinical trial results and safety events reported to the FDA. The agency eventually removed sibutramine from the market in 2010. The role of the petition was not mentioned in the FDA’s final announcement about the drug’s removal.

Still, while no one would fault the agency for focusing on safety, all drugs carry risks, even mild ones. Phenylephrine can raise blood pressure and is contraindicated for patients with hypertension or heart disease. Two individually “safe” drugs can also interact dangerously inside the body.

These comments were made during a joint meeting between the nonprescription drugs committee and the pediatric advisory committee in October 2007.

I stopped taking phenylephrine because it worked too well. Like absurdly well. Days of blocked nose then completely clear from one tablet within an hour. It made me rue the opposite problem with my nose dry and scratchy, even without taking any more it would last well into the next day. Milder remedies better for me. There’s no way you will convince me it doesn’t work.

Diethylene glycol in a cough medicine just killed dozens of kids in India

https://www.bmj.com/content/391/bmj.r2118