Clinic-in-the-Loop

Clinical trials are engines for scientific discovery. Better drugs require not just more trials, but also improved data collection, to create therapeutic feedback loops.

For the last several years, I have been trying to understand why biomedical progress, especially in therapeutics, has become less productive despite staggering advances in basic science.

I am not the only person vexed by this. In 2012, biotechnologist Jack Scannell formally described the dwindling returns on therapeutic investments, coining the term Eroom’s Law (Moore’s Law in reverse). Eroom’s law states that the inflation-adjusted cost to bring a new drug to market roughly doubles every nine years: a trend that has held since the 1950s. With the goal of upending Eroom’s law, I have spent the last year studying the structural bottlenecks that shape how new medicines are tested and the FDA’s role in such decisions.

Much of my time has been focused on clinical trials, which, despite their central role in the creation of pharmaceuticals, receive remarkably little systematic attention. This led me to launch the Clinical Trial Abundance Project, a framework aimed at increasing not only the number of clinical trials, but also their speed and how much we learn from them. Recently, I co-authored an essay with Scannell, arguing that making trials more efficient and informative is essential to breaking Eroom’s Law.

Critics of our essay, however, argued that making clinical trials more efficient risks treating biotechnology like a casino. In their view, making it easier to run clinical trials would risk allowing more potentially harmful drugs to be tested in patients and, instead, biotechnologists should focus on making better drugs that are more likely to gain approval. These critics see Clinical Trial Abundance as accepting the status quo of drug development rather than challenging it.

But this is a misunderstanding.

In fact, Clinical Trial Abundance and better hypotheses for drugs are not merely compatible, but self-reinforcing. Faster testing in the clinic creates a feedback loop: ideas become trials, trials generate rich data (including both successes and failures), these data improve models, and better models inform the next generation of ideas. In this view, the clinic is not an endpoint of discovery but a central component of it.

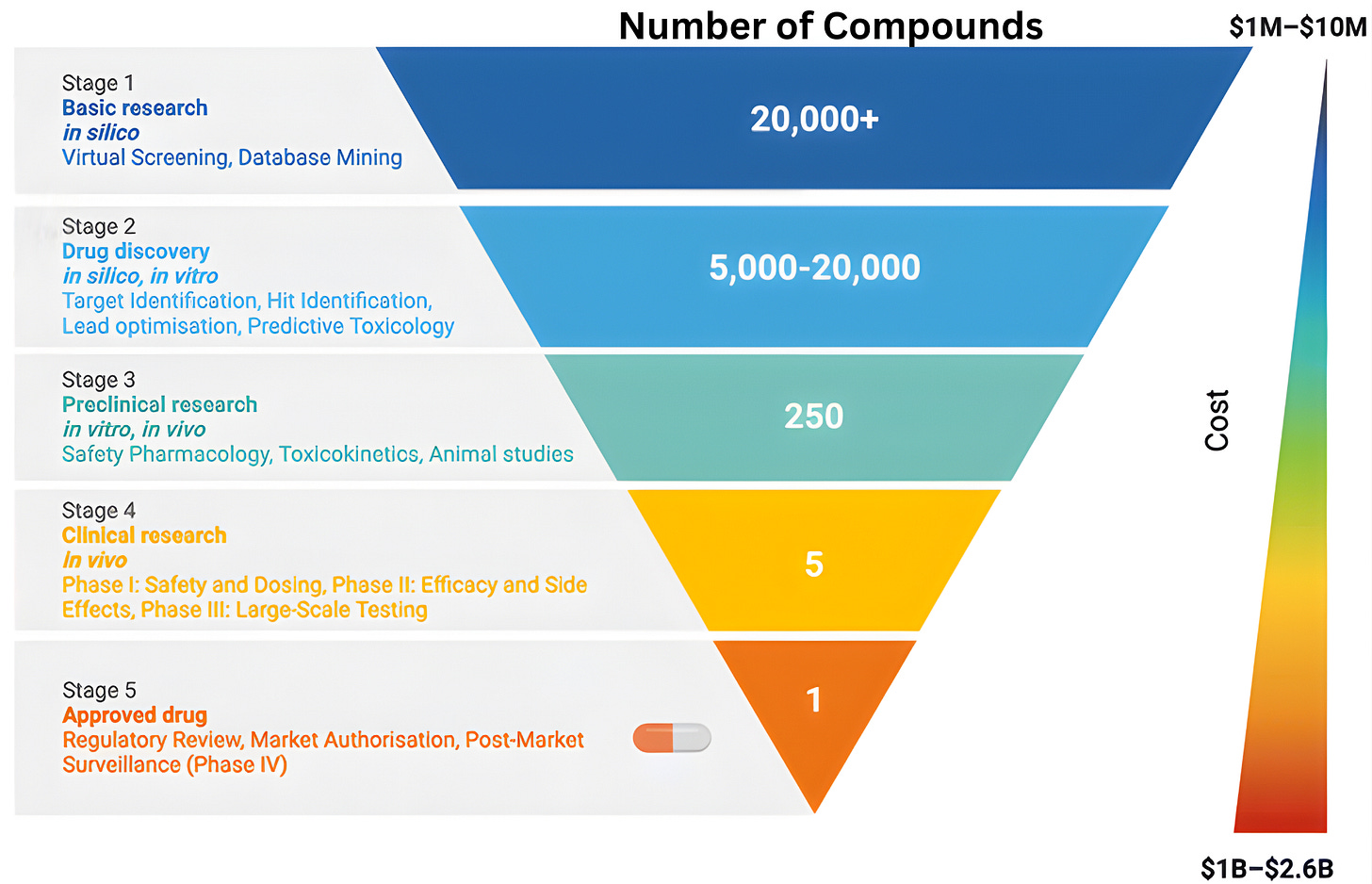

To understand why clinical abundance is important, we must step outside the prevailing view of clinical testing as a mere “validation step” for scientific ideas. The familiar funnel metaphor of drug discovery, depicting a linear progression from basic science to regulatory approval, reinforces the flawed notion of clinical testing as a passive filter designed to screen pre-existing ideas. While this model is narrowly correct in a regulatory sense, it obscures the clinic’s role as an active engine of discovery.

The reality is that clinical trials rarely just deliver a “yes/no” verdict on a drug’s efficacy. Instead, the history of drug development shows that many successful therapies emerged only after initial versions failed in specific, informative ways. When a trial fails, it provides a unique physiological stress test that reveals exactly where a drug’s design fell short. By collecting data from “failed” trials, we can transform negative results into experimental corrections for the next iteration.

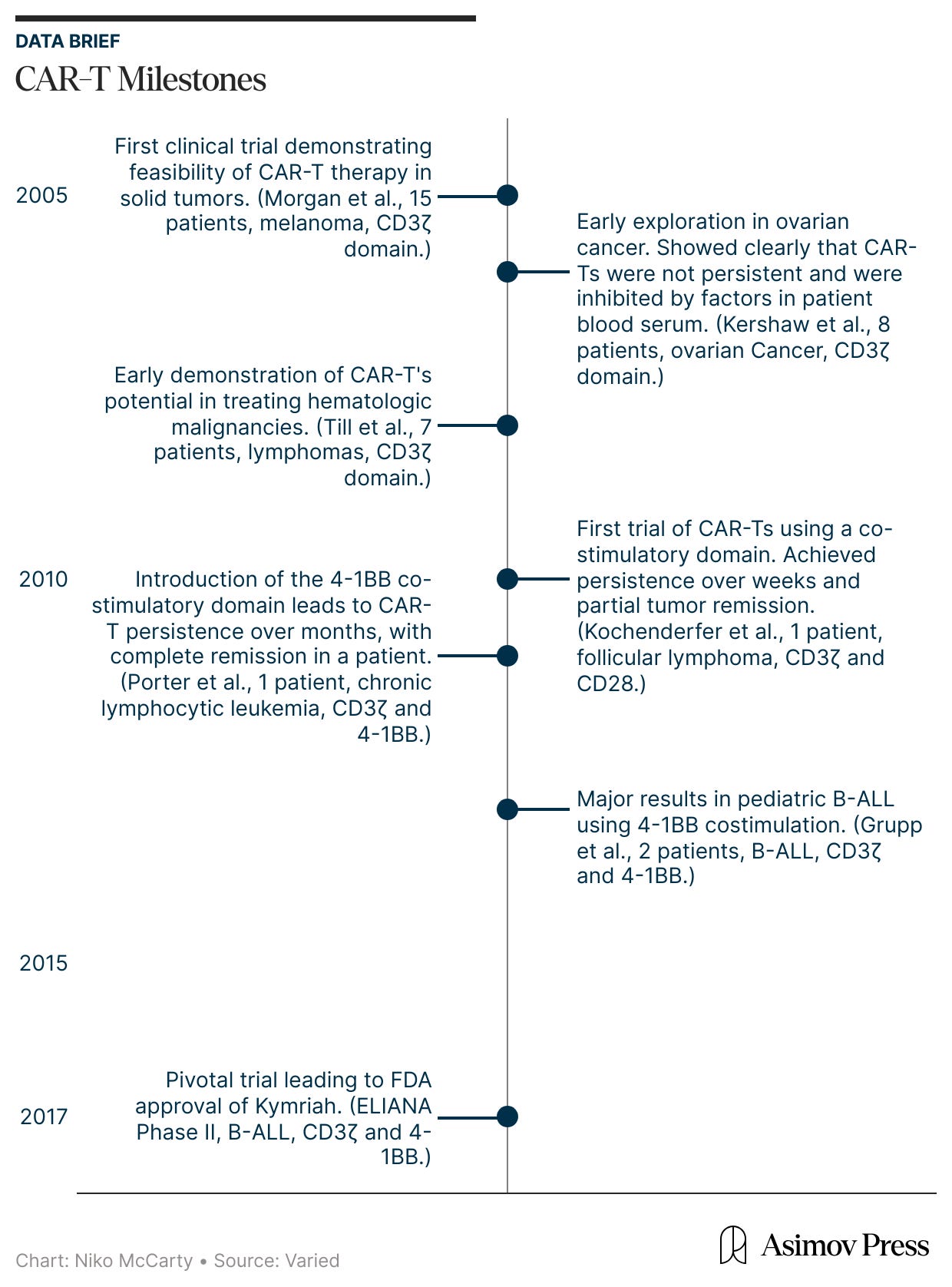

Consider CAR-T cell therapies. Once thought implausible or risky, CAR-T therapies now deliver long-term, treatment-free remissions in cancers where relapse had been almost certain.1 In pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and aggressive B-cell lymphomas, for example, CAR-T has cured patients who, previously, had been given only months to live.

CAR-T therapy works by turning a patient’s own immune cells into living drugs. Doctors collect T cells from the blood, genetically reprogram them to recognize a protein on cancer cells, and reinfuse the modified T-cells into the patient. These engineered cells expand inside the body, move to tumor sites, and destroy malignant cells.

In 2017, the FDA approved Kymriah, the first CAR-T therapy, for children and young adults with relapsed or refractory B-ALL, a cancer of arrested development in which immature blood cells, specifically B cells, multiply out of control while failing to mature into viable immune cells. Relapsed B-ALL is the most severe form of the disease, because it means the cancer has returned after prior therapy. Even with aggressive care, only 10-20 percent of patients with relapsed or refractory B-ALL survived beyond five years.

Against this backdrop, Kymriah received accelerated approval from the FDA based on results from the Phase II ELIANA trial, a global, multicenter study sponsored by Novartis. In ELIANA, 82 percent of treated patients achieved complete remission, and subsequent follow-up analyses revealed that five-year survival rose to approximately 55-60 percent.

ELIANA was not a sudden breakthrough, though. It was, rather, the culmination of nearly two decades of clinical studies. During this period, CAR-T therapies evolved through repeated failure in the clinic, as careful studies of underwhelming results spurred new ideas to correct them. The ELIANA trial was led by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, a group that had spent years studying CAR-T cells directly in patients well before regulatory approval.

In the mid-2000s, the earliest CAR-T therapies first entered human testing. And they emerged from a fundamental question: is it possible to engineer and redirect the T cell’s innate killing power against malignant cells?

Two well-established biological concepts made this seem plausible. First, T cells are extraordinarily cytotoxic.2 However, their natural activation is governed by a “layered permission” system, meaning they cannot recognize targets directly, but must wait for other cells to process and present protein fragments in a precise molecular context. While this evolutionary safeguard keeps us from being attacked by our own immune system, it also provides cancer with many opportunities to evade detection by suppressing these signaling pathways.

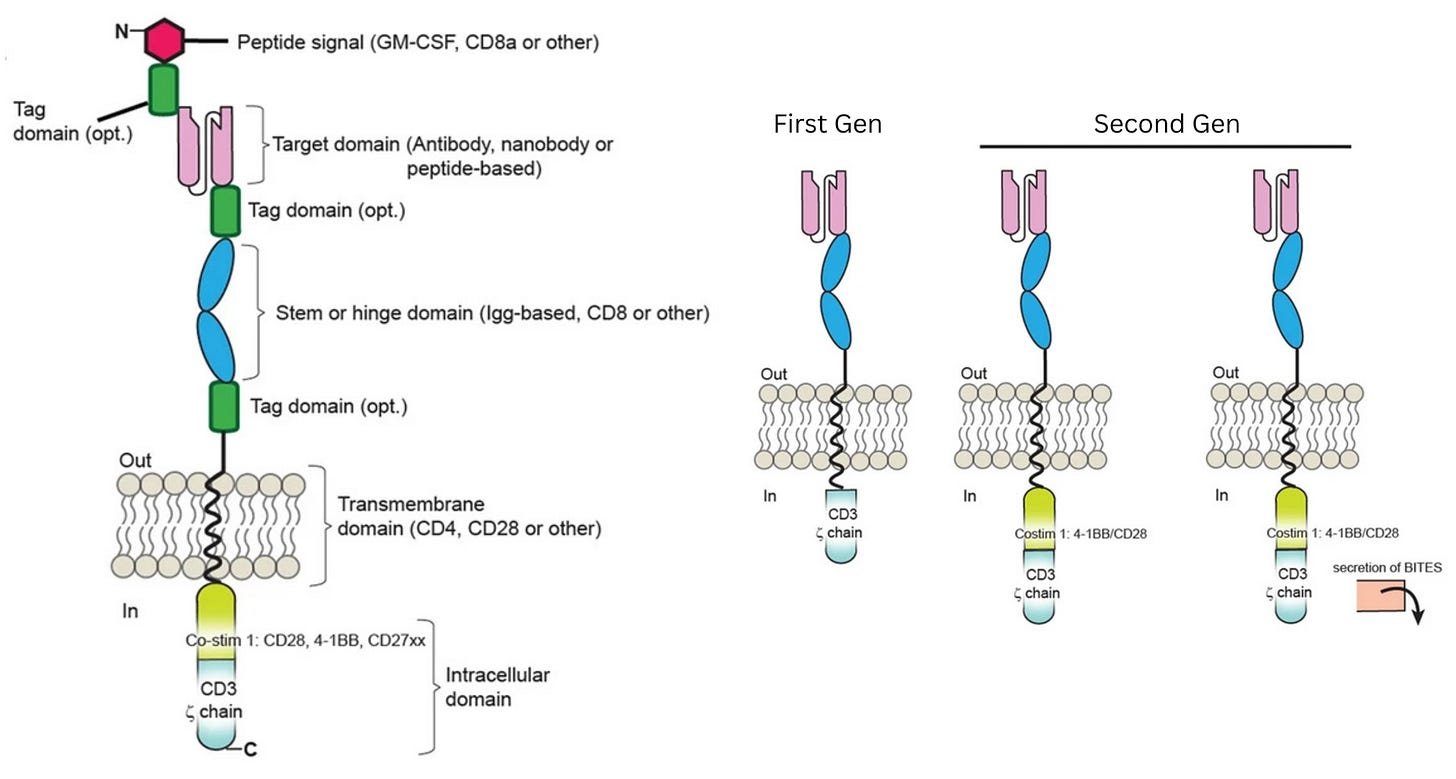

To bypass these safeguards, researchers relied on a second insight: the ability of antibodies to bind directly and precisely to proteins on the surface of cells, called antigens. By equipping T cells with a synthetic Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR), bioengineers created a functional shortcut that bypassed the need for permission systems. This receptor uses antibody-style recognition to lock onto a cancer cell and is wired directly to CD3ζ, a signaling molecule that triggers the T cell’s internal “kill switch.” The moment the receptor engages its target, it flips the internal switch, activating the cell’s killing program.

In laboratory experiments, these first-generation CAR-Ts were formidable, displaying antigen recognition and potent killing power against tumor cell lines. Yet, this in vitro prowess vanished in patients and did not yield durable clinical responses. Understanding why this happened, though, was not simple. The failure could have been caused by a breakdown in in vivo antigen recognition, poor signaling strength, or other defects that only emerged after the cells were injected into the body.

Progress in understanding why early CAR-T therapies did not live up to their promise came from treating first-in-human trials not simply as therapeutic attempts, but as opportunities to learn. These information-dense studies were conducted throughout the mid- and late-2000s and were relatively small (usually enrolling fewer than ten patients). However, they were designed to be maximally revealing. Researchers used many tools to monitor CAR-T persistence and activity in the body, turning information from a small number of patients into a mechanistic understanding.

One such tool was quantitative PCR (qPCR), a lab method that detects and counts specific DNA sequences, which allowed researchers to measure how many CAR-T cells were in patients' blood. This showed that CAR-T cells successfully entered the body and were easy to detect after infusion. But the signal quickly faded, suggesting that the cells died off quickly. Other experiments shed light on the problem: CAR-T cells could recognize and eliminate cancer cells in patients — meaning antigen recognition was working — but their functional activity fell over time, suggesting that something in the blood was blocking them.

At this point, the diagnosis of why first-generation CAR-T therapies were failing matched long-standing insights from basic immunology. Decades of research had shown that T cells are not governed by a single on-off switch: signaling through CD3ζ provides only the first activation signal. To keep working, T cells need additional “costimulatory” signals,3 delivered through receptors such as CD28 or 4-1BB. First-generation CARs had been designed to deliver signal one without signal two, which explained their poor performance.

This hypothesis guided the next wave of clinical experiments, which investigated whether adding a costimulatory domain would make CAR-T cells more effective at clearing tumors in vivo.

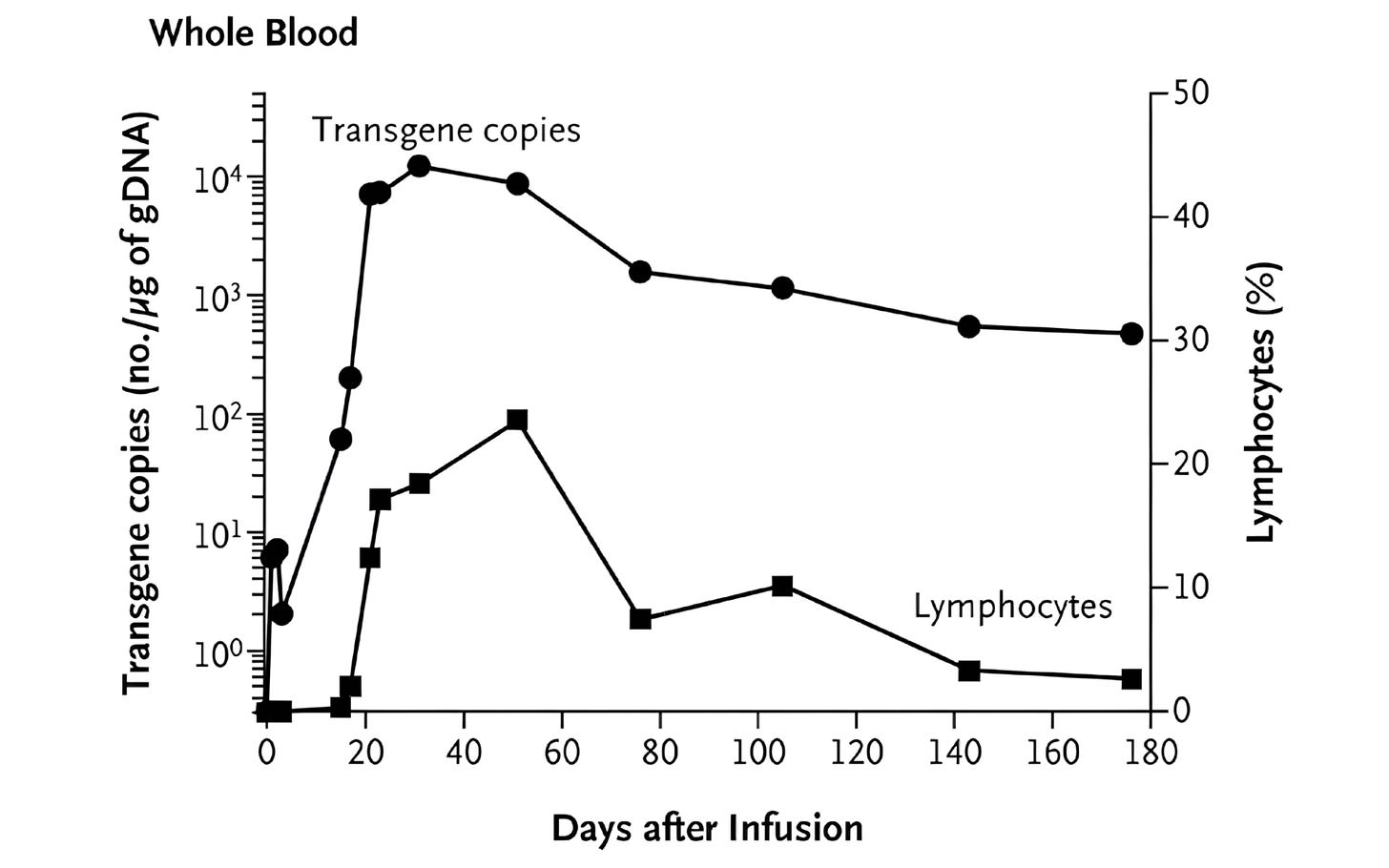

The field-defining result came from Carl June’s group at the University of Pennsylvania. June and colleagues explored a costimulatory domain called 4-1BB. In a first-in-human study published in 2011, they treated a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia using CAR-T cells containing both CD3ζ and 4-1BB. They also administered a dose that was remarkably small by cell therapy standards at that time: just 1.5 × 10⁵ CAR-T cells per kilogram of body weight. (A first-generation CAR-T trial targeting renal cell carcinoma, published in 2013, used a dose more than 100-times higher.)

What followed was unprecedented. The CAR-T cells multiplied more than a thousandfold in patients, at their peak comprising a large fraction of immune cells in the blood. The CAR-T cells also persisted for months. Now, at last, CAR-T cells were a long-lived and self-maintaining immune population. Many cancer patients treated with these second-generation CAR-T therapies have achieved complete remission.

The next step, though, was asking whether the same CAR-T behavior would work in a faster, more aggressive blood cancer, such as B-ALL. In 2013, Carl June’s lab reported striking results in two children with relapsed B-ALL, again showing that the engineered T cells could multiply, persist, and drive cancer into remission.

All of these lessons were built into ELIANA, the study that ultimately supported Kymriah’s approval. Led by Stephan Grupp, who had treated the earliest pediatric patients and worked closely with June, ELIANA translated the early insights into standardized practice. This trial codified chemotherapy given before CAR-T infusion, scaled up cell manufacturing, and measured success using tools like qPCR.

Viewed through this lens, clinical trials are not an alternative to basic science, but rather a mechanism within it that closes a feedback loop. Foundational immunology, antibody engineering, and molecular biology made first-generation CAR-T cells possible in the first place, but early human trials quickly revealed that these designs were incomplete and suggested ways to fix them.

Yet theory alone did not prove this would work; the expansion and persistence observed with 4-1BB–based CAR-T cells came as a genuine surprise even to the therapy's designers. “It was unexpected,” they reported, “that the very low dose of chimeric antigen receptor T cells that we infused would result in a clinically evident antitumor response.”

This shows why the “casino biotech” critique is flawed. It assumes that experimentation simply reveals a fixed probability of success. But trials can change those probabilities. When clinical testing is understood as part of a continuous feedback system, optimizing trial efficiency is not about accepting failure but about learning fast enough to make success more likely.

The most discovery-rich experiments are often not massive Phase III trials, either, but small, academic, investigator-initiated studies that sit close to the design loop.4 These are also the trials most burdened by regulatory, institutional, and manufacturing bottlenecks.

For example, early CAR-T studies are often required to use full “good manufacturing practice” (GMP) facilities — the same industrial standards used to mass-produce approved therapies — which can drive costs into the millions even for studies with just a handful of patients. Many researchers argue that such custom, tightly monitored studies do not need full commercial-scale GMP, and Australia offers a real-world example: Its regulatory system allows small-scale trials to use more flexible manufacturing under strict oversight, enabling safe human studies at far lower cost than in the U.S. or Europe. More worrying still, the researchers I interviewed who run these trials consistently report that institutional bureaucracy has become harder to overcome in the last several years.

If we want biomedical progress to accelerate, we should stop treating clinical trials as an afterthought or as a binary “yes/no” part of drug development. Instead, we should ask how to make the design-build-test loop better in humans. Some answers will be policy-driven, like lowering barriers to ethical investigator-initiated trials, enabling adaptive development, and making better use of clinical data. Others will be technological, including richer in-human measurement and better monitoring.

The aim of the Clinical Trial Abundance project is thus broader than merely proposing policy solutions for accelerating trials. It seeks to remind people of the importance of in-human data as a tool for scientific discovery.

Ruxandra Teslo is a fellow at Renaissance Philanthropy and co-founder of the Clinical Trial Abundance project. She writes about the intersection of science, culture and policy at her Substack. She holds a PhD in Genomics from Cambridge University.

Header image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Cite: Teslo, R. “Clinic-in-the-Loop.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/38jw-33ht

Relapse is when a disease returns or worsens after a period during which it had improved or appeared to be under control post-treatment.

Derived from the Greek words for “cell” (kyto) and “poison” (toxikon), cytotoxic just means the ability to damage or kill living cells.

A costimulatory signal is a secondary activation signal that T cells require, in addition to the primary signal from antigen recognition, to become fully activated.

Optimizing these massive, pivotal trials will be an important way to compress the macro-feedback loops of drug development and lower entry barriers for novel therapies.

According to IQVIA, trials are increasingly complex (profusion of endpoints, inclusion/exclusion criteria etc) and therefore costly. As you’ve pointed out there is significant informational value “even” in failed trials, as these can form the basis of subsequent success. There is clearly some trade-off between the need to both expedite clinical trials and to run information rich experiments and I don’t know where the optimum setting lies.

My own experience is that often companies run trials using almost the exact same criteria as their competitors in an attempt to derisk the asset. Not an optimal solution but an understandable one.

Wonderful article, thanks for writing this. The notion that real-world problem-and-technology-rich use environments can be "engines" for learning and scientific discovery is super under appreciated. I like to call it "reverse translation" and "true" Pasteur's quadrant research (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5600892). I'm more familiar with the physical sciences, so know how important it is there. It makes sense that it is just as important in the biomedical sciences. Also thanks to Smrithi Sunil for calling attention to this nice article!