The Origins of Agar

First introduced into laboratories in 1881, agar remains indispensable as a culture medium.

This essay will appear in our forthcoming book, “Making the Modern Laboratory,” to be published later this year.

In 1942, at the height of British industrial war mobilization, an unlikely cohort scavenged the nation’s coastline for a precious substance. Among them were researchers, lighthouse keepers, members of the Royal Air Force and the Junior Red Cross, plant collectors from the County Herb Committee, Scouts and Sea Scouts, schoolteachers and students. They were looking for fronds and tufts of seaweed containing agar, a complex polysaccharide that forms the rigid cell walls of certain red algae.

The British weren’t alone in their hunt. Chileans, New Zealanders, and South Africans, among others, were also scrambling to source this strategic substance. A few months after the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. War Production Board restricted American civilian use of agar in jellies, desserts, and laxatives so that the military could source a larger supply; it considered agar a “critical war material” alongside copper, nickel, and rubber.1 Only Nazi Germany could rest easy, relying on stocks from its ally Japan, where agar seaweed grew in abundance, shipped through the Indian Ocean by submarine.2

Without agar, countries could not produce vaccines or the “miracle drug” penicillin, especially critical in wartime. In fact, they risked a “breakdown of [the] public health service” that would have had “far-reaching and serious results,” according to Lieutenant-General Ernest Bradfield. Extracted from marine algae and solidified into a jelly-like substrate, agar provides the surface on which scientists grow colonies of microbes for vaccine production and antibiotic testing. “The most important service that agar renders to mankind, in war or in peace, is as a bacteriological culture medium,” wrote oceanographer C.K. Tseng in a 1944 essay titled “A Seaweed Goes to War.”3

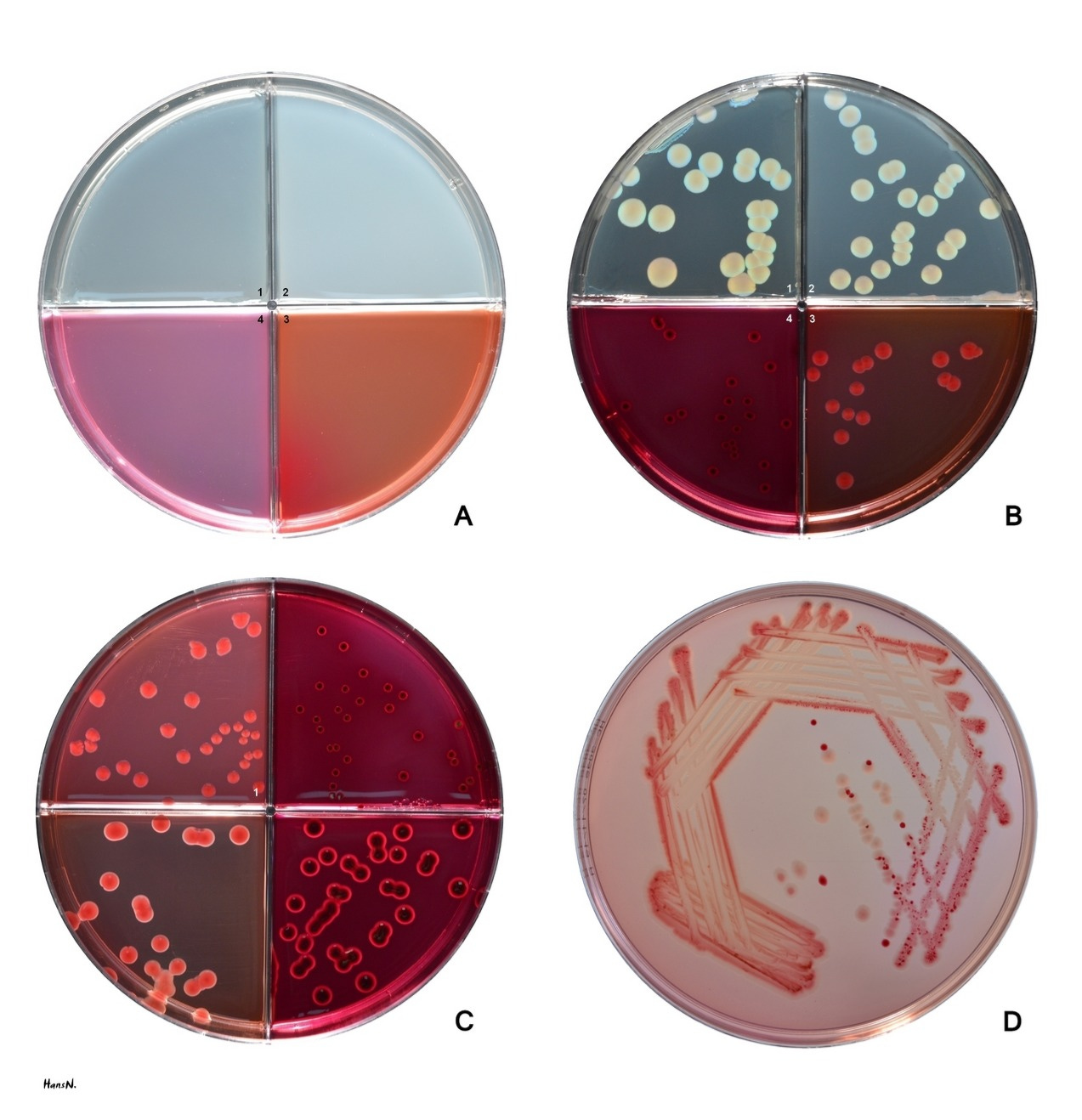

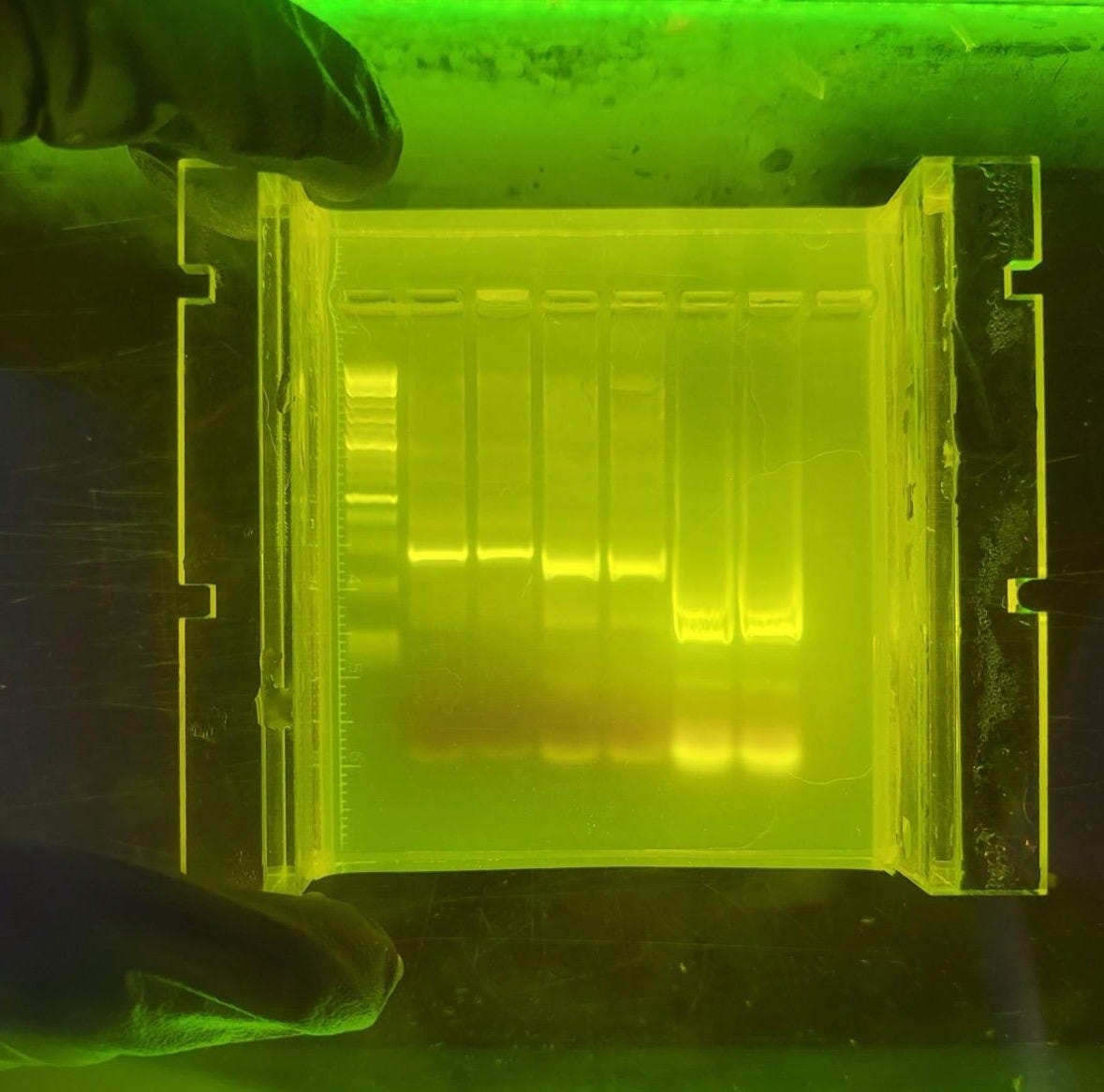

Agar was first introduced into the laboratory in 1881. Since then, microbiologists have depended on agar to create strong jellies. When microorganisms are streaked or plated onto this jellied surface and incubated, individual cells multiply into distinct colonies that scientists can easily observe, select, and propagate for further experiments. Many of the most important findings in biological research of the last 150 years or so — including the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tool — have been enabled by agar.4 Agarose, a derivative of agar, is also essential in molecular biology techniques like gel electrophoresis, where its porous gel matrix separates DNA fragments by size, enabling researchers to analyze and isolate specific genetic sequences.

Agar is so critical that since WWII, scientists have tried to find alternatives in the event of a supply chain breakdown, especially as recent shortages have caused similar alarm. But while other colloid jellies have emerged, agar remains integral to laboratory protocols because no alternatives can yet compete on performance, cost, and ease of use.

From Sea to Table

Microbiologists have been growing microbes on agar plates for nearly 150 years, but agar’s discovery dates back to a happy accident in a mid-17th-century kitchen. Legend has it that on a cold winter day, a Japanese innkeeper cooked tokoroten soup, a Chinese agar seaweed recipe known in Japan for centuries. After the meal, the innkeeper discarded the leftovers outside and noticed the next morning that the sun had turned the defrosting jelly into a porous mass. Intrigued, the innkeeper was said to have boiled the substance again, reconstituting the jelly. Since this discovery, agar has become a staple in many Japanese desserts, from yokan to anmitsu.

Industrial production of kanten (the Japanese name for agar, which translates as “cold weather” or “frozen sky”) began in Japan in the mid-19th century by natural freeze drying, a technique that simultaneously dehydrates and purifies the agar. Seaweed is first washed and boiled to extract the agar, after which the solution is filtered and placed in boxes or trays at room temperature to congeal. The jelly is then cut into slabs called namaten, which can be further processed into noodle-like strips by pushing the slabs through a press. These noodles are finally spread out in layers onto reed mats and exposed to the sun and freezing temperatures for several weeks to yield purified agar. Although this traditional way of producing kanten is disappearing, even today’s industrial-scale manufacturing of agar relies on repeated cycles of boiling, freezing, and thawing.

Because of its capacity to be freeze-dried and reconstituted, agar is considered a “physical jelly” (that is, a jelly that sets and melts with temperature changes without needing any additives). This property makes dry agar easy to ship and preserve for long periods of time.5

Over the years, agar found its way around the world into many cuisines, including those of China (where it’s called “unicorn vegetable” or “frozen powder”), France (sometimes called gélose), India (called “China grass”), Indonesia (called agar-agar, which translates simply as “jelly”), Mexico (called dulce de agar, or agar sweets), and the Philippines (known as gulaman).

Agar is prized among chefs for its ability to form firm, heat-stable gels at remarkably low concentrations — typically just 0.5-2 percent by weight. Culinary agar is available as powder, flakes, strips, or blocks, and makes up about 90 percent of the global use of agar. Unlike gelatine, which melts at body temperature, agar gels remain solid up to about 185°F (85°C), making it ideal for setting dishes served at room temperature or warmer. It is also flavorless and odorless, vegan and halal, and can create both delicate jellies and firm aspics. Yet, while increasingly employed in kitchens worldwide, agar had not yet entered the laboratory.

Before agar, microbiologists had experimented with other foodstuffs as microbial media. They turned to substances rich in the starches, proteins, sugars, fats, and minerals that organisms need for growth, testing with broths, bread, potatoes, polenta, egg whites, coagulated blood serums, and gelatine. However, none worked particularly well: all were easily broken down by heat and microbial enzymes, and their surface, once colonized, became mushy and unsuitable for isolating microbes.

This was especially vexing to physician and bacteriologist Robert Koch, who, in seeking to culture his bacteria, “bent all his power to attain the desired result by a simple and consistently successful method,” wrote bacteriologist and historian William Bulloch in his 1938 book, The History of Bacteriology. “He attempted to obtain a good medium which was at once sterile, transparent, and solid” and got some results with gelatine.6 But gelatine is easily digested by many microbes and melts at precisely the temperatures at which the disease-causing microbes Koch wanted to study grow best.

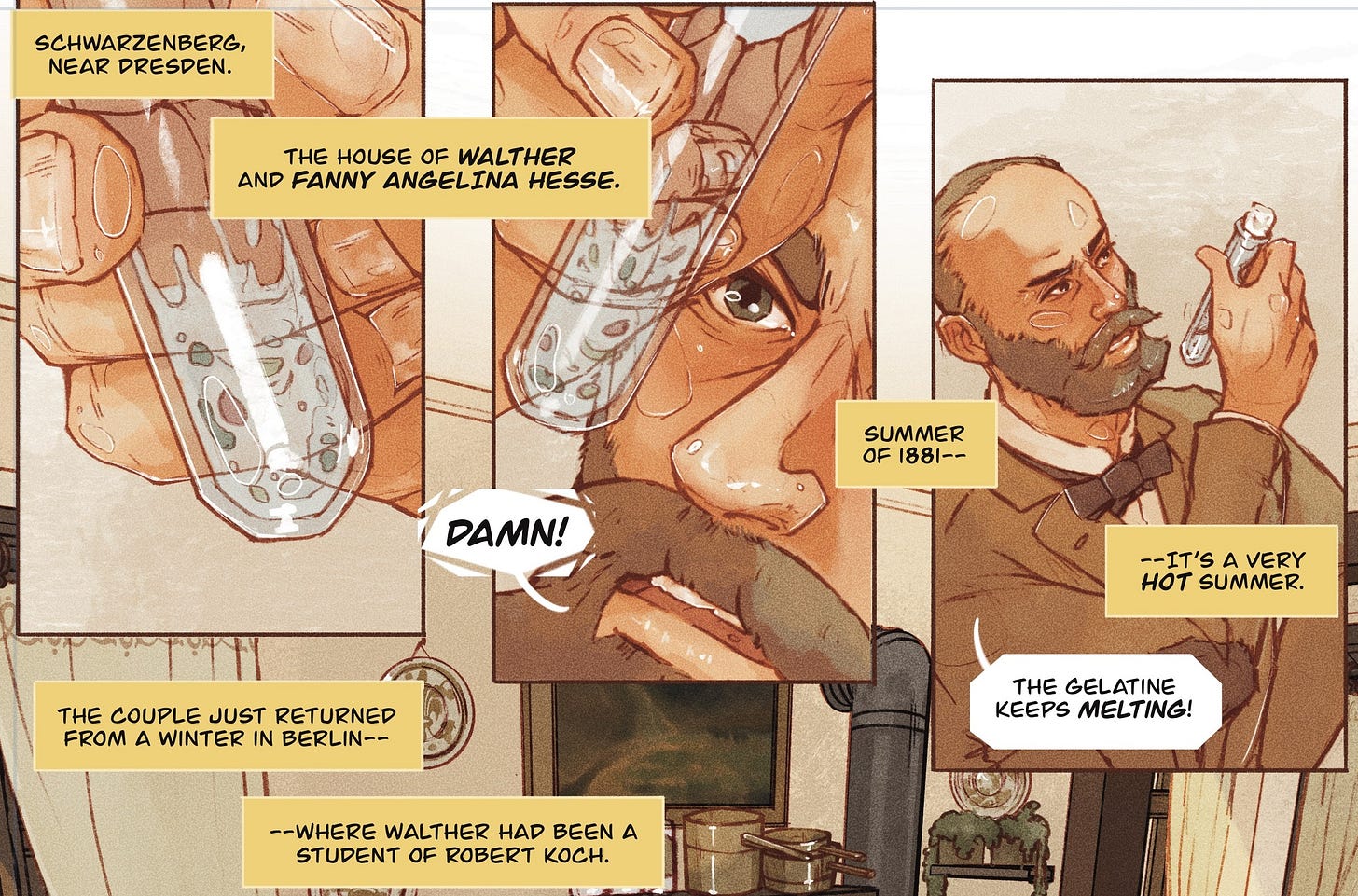

The woman who ultimately discovered the superior features of agar as a growth medium and brought it to Koch’s attention was Fanny Angelina Hesse. Her foundational contribution to the nascent field of microbiology is often omitted from textbooks. In other cases, she is unflatteringly referred to as a “German housewife” or as “Frau Hesse,” or dismissed as an unnamed technician.

From Plate to Petri Dish

Fanny Angelina (née Eilshemius, from a Dutch father) grew up in Kearny, New Jersey. During her childhood, her family learned from a Dutch friend or neighbor about agar-agar, a common ingredient in jelly desserts in Java (Indonesia), then a Dutch colony. Her mother and, later, Fanny Angelina herself, began to cook with it.

In 1874, Fanny Angelina married physician and bacteriologist Walther Hesse, an investigator of air quality and, specifically, air-borne microbes. In the Winter of 1880-81, Hesse became a research student with Koch in Berlin and experienced firsthand the difficulty of growing microbes on gelatine and the other growth media used at the time.

While raising three children and taking care of the household, Fanny Angelina Hesse supported, documented, and archived her husband’s work, creating stunning scientific illustrations of bacterial and fungal colonies. During the hot Summer of 1881, she watched as Hesse struggled with gelatine-based growth media. Fanny Angelina, recalling the stability of her agar-based desserts, suggested that they try that instead. Hesse wrote a letter to Koch informing him about the switch, and Koch mentioned agar for the first time in his 1882 groundbreaking paper on the discovery of the tuberculosis bacillus.

The change to agar was a marked improvement. The jelly is so effective that it is still an invariable ingredient in what is known today as the “Koch’s plating technique” or the “culture plating method.” As Koch himself noted in 1909: “These new methods proved so helpful…that one could regard them as the keys for the further investigation of microorganisms…Discoveries fell into our laps like ripe fruits.”

Once Koch established the methods to grow pure cultures of bacteria like tuberculosis and anthrax, he demonstrated for the first time that microbes can cause diseases, a feat that earned him the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

However, Koch never credited the Hesses for their discovery of bacteriological agar, perhaps because, at the time, he failed to recognize its importance. Even after he received the insight about agar from the Hesses, Koch stuck with gelatine for years. In 1883-84, during his first medical expedition to Egypt and India to investigate cholera, he tried and failed to grow the cholera bacterium on gelatine media in the hot climate of Cairo (despite using a half-open fridge for incubation), only succeeding in the colder winter of Calcutta.

It is difficult to know exactly when the shift from gelatine to agar occurred. As often happens for scientific breakthroughs, agar was likely adopted incrementally alongside the use of other growth media. In 1913, for example, the first diagnosis of Serratia marcescens as a human pathogen was made by growing it on agar as well as on potatoes.

Nevertheless, by 1905, a report on the seaweed industries in Japan noted the “very important use [of pure-grade agar] as a culture medium in bacteriological work.” It’s safe to say that, around the turn of the 20th century, agar had moved from an inconspicuous kitchen jelly to an indispensable scientific substance.

A Strategic Substance

Several properties of agar render it a superior jelly. Agar isn’t broken down by microbial enzymes apart from a few species (including bacteria living in marine and freshwater habitats), and it dissolves well in boiling water, making it easy to sterilize. The jelly doesn’t react with the ingredients of a broth, whose composition can be adjusted to meet the nutritional requirements of different microbes, and sets to a firm gel without the need for refrigeration.

Agar’s low viscosity also makes it easy to pour into Petri dishes, and its transparency permits observation of microbes growing on its surface.7 Also aiding in this is its low syneresis (extrusion of water from the gel), guaranteeing less surface “sweating”: Once a plate is inoculated, bacterial colonies stay in place and do not mix.

The jelly is chemically inert since no additives are needed for gelation. This allows chemicals dissolved in the jelly’s aqueous phase to diffuse well, a prerequisite for testing if certain species or strains are resistant to antibiotics or antifungals. In these simple assays, zones of growth inhibition of bacteria or fungi (or their absence) point to the effectiveness of (or resistance towards) antibiotics or antifungals.

But agar’s superior qualities come with complex chemistry. “To speak of agar as a single substance of certain (if known) chemical structure is probably a mistake,” wrote phycologist Harold Humm in a 1947 article. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, agar is merely recognized as “a hydrophilic colloid extracted from certain seaweeds of the Rhodophyceae class.” In terms of its actual composition, agar is mostly a combination of two polysaccharides, agaropectin and agarose, which themselves are complex and poorly-characterized polysaccharides made mostly (but not exclusively) from the simple sugar galactose.8

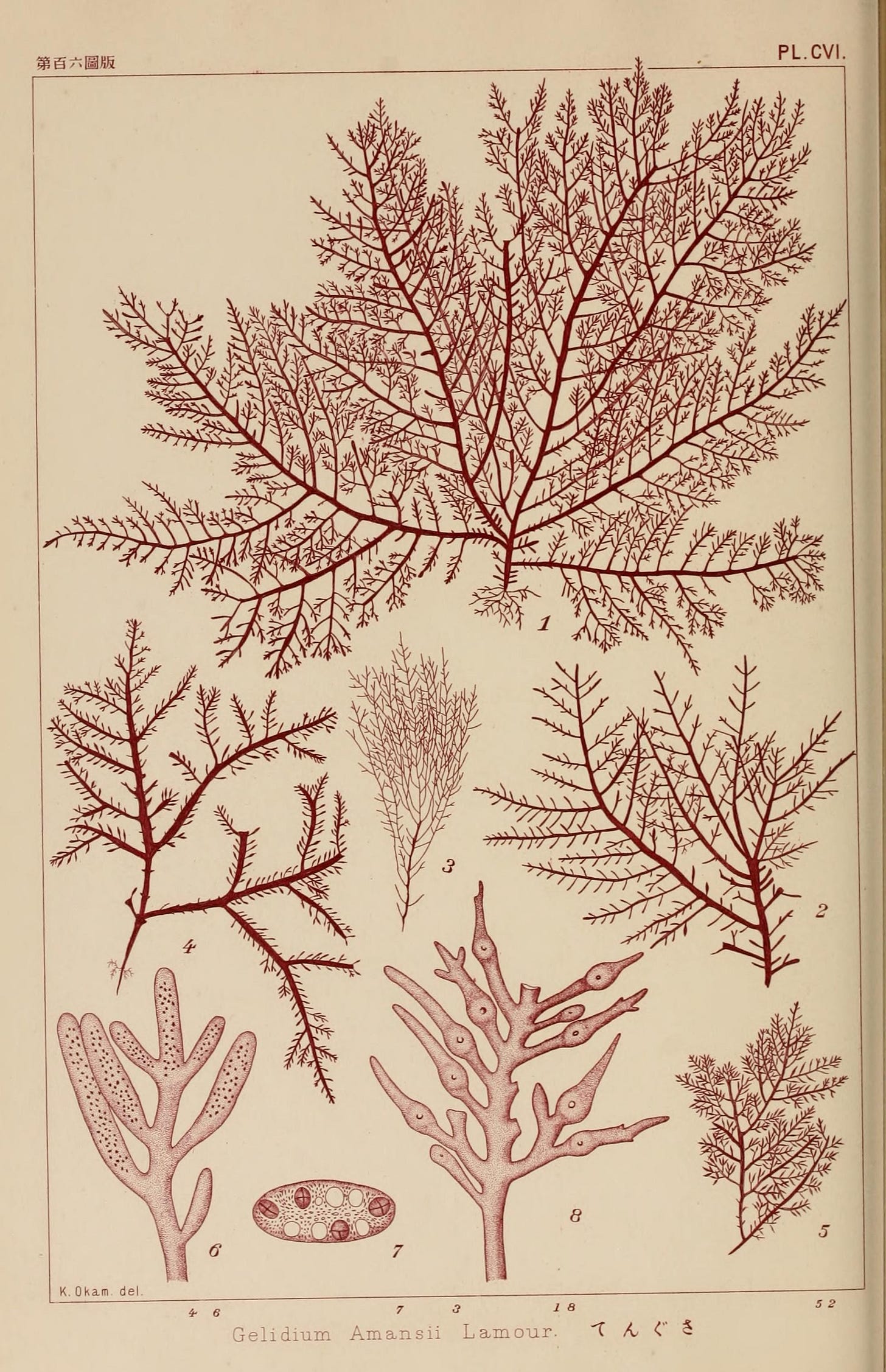

Agar comes from multiple sources, as many red seaweeds are “agarophytes” (that is, seaweeds containing agar in their cell walls). Species of Gelidium are the most important source of bacteriological (lab-grade) agar. Other main agarophytes, largely used for culinary agar, include red seaweeds from the genera Gracilaria, Pterocladia, Ahnfeltia, and others. Species from the genera Eucheuma, Gigartina, and Chondrus have been used as agarophytes in research during agar shortages.9

One striking characteristic of Gelidium is that it must be wild-harvested rather than farmed. Unlike Gracilaria for culinary agar production, Gelidium grows slowly and thrives only in cold, turbulent waters over rocky seabeds, conditions nearly impossible to replicate in aquaculture. This dependence on wild harvesting explains the need for seaweed collectors during WWII, and continues to make Gelidium a strategically critical resource.

While Gelidium seaweeds can be collected by gathering fragments washed ashore, mass production of agar requires steady, large quantities.10 Harvesters in New Zealand during WWII had to “walk beside a boat, waist to armpit deep in water and feel for the weed with their feet.” Handling large volumes of wet seaweed (which yields less than five percent agar) was challenging. Then as now, when Gelidium is harvested by scuba divers from rocky seabeds, collectors have to understand the life cycle of the algae, find the most likely locations for its growth, and prevent overharvesting to safeguard future yields.

Given its auspicious position on the Atlantic coastline, Morocco has been the main source of Gelidium for at least two decades, and demand for bacteriological agar continues to grow. Yearly global consumption increased from 250 tons to 700 tons between 1993 and 2018, and is currently estimated at around 1,200-1,800 tons per year, according to Pelayo Cobos, commercial director of Europe’s largest producer of agar, Roko Agar.

The Future of Agar

Amid such rising demand, it’s understandable that researchers worried when Morocco reduced exports of agarophytes in 2015. This shortage — due to a combination of overharvesting, climate warming, and an economic shift to internal manufacturing in the North African country — not only caused alarm but a three-fold price increase of wholesale bacteriological agar, which reached $35-45 per kilogram. (At the time of writing this in late 2025, factory agar prices are sitting at about $30 per kilogram, according to Cobos.)

A few years later, in 2024, researchers in multiple labs were horrified to notice toxic batches of agar for reasons as yet unclear. After they observed a worrying lack of microbial growth (impeding their ability to carry out basic experiments), they switched to different agar suppliers, and their results improved.

This was not the first time that microbiologists experienced problems with agar. A phenomenon called “The Great Plate Count Anomaly” baffled researchers in the early 20th century when they observed that the number of cells seen under a microscope didn’t match the actual number of colonies growing on an agar plate. Investigating this discrepancy, researchers found agar itself to be the culprit: when nutrient broths are heated with agar during boiling, harmful byproducts (hydroperoxide) can form due to the reaction of agar with phosphate minerals contained in the media. Researchers can avoid this by autoclaving agar separately from the nutrient broth, or by reducing the amount of agar used.

This anomaly is indicative of the larger challenge of culturing various microbial species, referred to as microbial “unculturability.” This cannot be explained by the use of agar alone or by the substitution of an alternative gelling agent, but rather by the difficulties in consistently recreating on an agar plate the multi-variable environment in which microbes grow naturally. Given such challenges, the risk of shortages, and the vulnerabilities of the agar supply chain, why is it so difficult to find suitable alternatives?

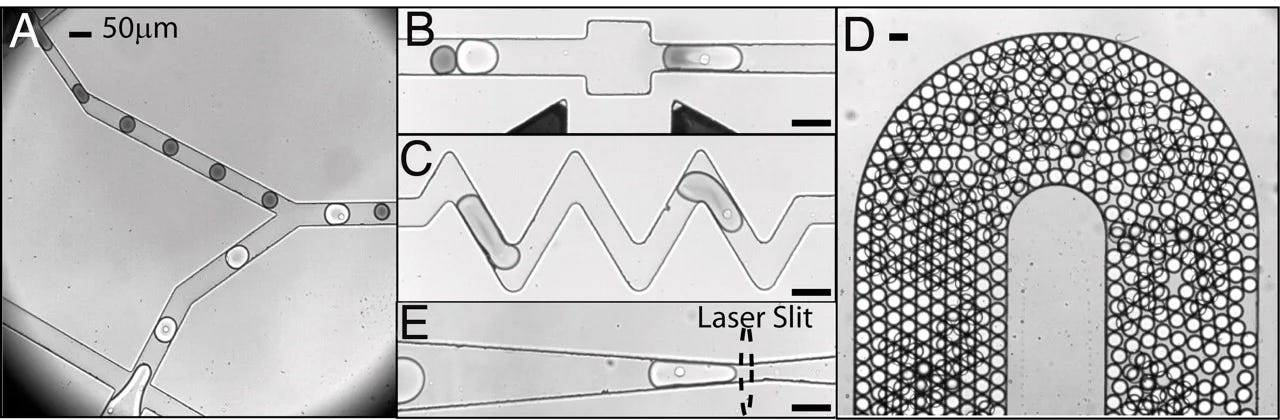

It is not for lack of trying. In some cases, microbiologists have ditched the Petri dish altogether, using microfluidics for manipulating and growing cells. However, these approaches aren’t likely to be adopted at scale as they require less common, less practical, and more expensive devices. So, what about other growth media?

By WWII, scientists had already begun looking at alternative gelling substances for routine use in bacteriology, but concluded that agar was still better as it is both firmer and easier to handle. Today, some specialized microbiology applications use the colloid carrageenan (extracted from red seaweed Chondrus crispus, or “Irish Moss”), a more transparent and less auto-fluorescent alternative to agar (agar emits its own background fluorescence when excited by light). However, for routine bacteriological use, carrageenan is more difficult to dissolve, requires higher concentrations, can degrade at high temperatures, and forms weaker gels, which may result in puncturing its surface during the plating of cells.

In some cases, alternative gelling agents might provide faster results. Researchers observed that bacterial cellulose and another bacterial polysaccharide, Eladium, allow a 50 percent increased growth rate for various bacteria and yeasts (as compared to their growth on agar), including higher biomass yields or faster detectable biofilm formation. However, both substances are still not as cheap and readily available as agar.

Guar gum, a plant colloid, costs less than agar and is better suited for growing thermophilic bacteria, but is also more difficult to handle, being more viscous and less transparent. The bacterial polysaccharide xanthan is cheaper as well but forms weaker jellies that, as with carrageenan, might result in puncturing its surface. Other colloids, like alginate (from brown seaweed) and gellan gum (from a bacterium), don’t set solely based on temperature and require additives for gelation. These additives might interfere with microbial growth and make the preparation of those jellies less handy than agar plates.

Thus, despite much effort, no gelling agent has yet been discovered that possesses all the properties and benefits of agar. Agar continues to be the best all-arounder: versatile, cheap, and established. And, if Gelidium agar should ever run out, and another colloid is not at hand, microbiologists could revert to culinary agar, which, although not as pure and transparent, offers a low-cost alternative to lab-grade agar.

It’s also worth noting that even if alternatives superior to agar were found, scientists are reluctant to abandon established protocols (even when microbiologists do use other jellies, they often still add agar to the mix, for example, to increase the gel strength of the solid media). As agar has been the standard gelling agent in microbiology for around 150 years, an enormous infrastructure of standardized methods, reference values, and quality control procedures has emerged around its specific properties. Switching to a different medium (even a superior one) means results may not be directly comparable to decades of published literature or to other laboratories’ findings.

So it is that agar continues to be the jelly of choice in laboratories around the world. As Humm wrote in 1947: “Today, the most important product obtained from seaweeds is agar, a widely-used commodity but one that is not well known to the general public.” Almost 80 years later, it might be better known, but its importance hasn’t dwindled.

Corrado Nai has a Ph.D. in microbiology and is a science writer with bylines in New Scientist, Smithsonian Magazine, Small Things Considered, Asimov Press, and many more. He is currently writing a graphic novel about Fanny Angelina Hesse and the introduction of agar in the lab called The Dessert that Changed the World, which can be followed and supported on Patreon.

Thanks to Steven Forsythe for sharing a report on the use of agar seaweed in Britain during WWII, Barbara Buchberger at the Robert Koch Institute for pointing out Koch’s use of gelatine for the identification of cholera, and the surviving relative of Fanny Angelina Hesse for sharing a trove of unpublished material.

Cite: Nai, C. “The Origins of Agar.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/12pq-97ht

A full list of these materials can be found at (psfa0134, pg. 9).

Japan halted exports to other countries for fear that agar supported their development of biowarfare weapons. A few years before, Nazi Germany allegedly tested the efficacy of biowarfare attacks with another curious microbe, Serratia marcescens, dubbed “the miracle bacterium.” According to a much-talked about report by investigative journalist Henry Wickham Steed titled “Aerial Warfare: Secret German Plans” members of a secret Luft-Gas-Angriff (Air Gas Attack) Department spread the S. marcescens in the subterranean train networks of Paris and London and measured its reach armed with Petri dishes and agar plates.

It wasn’t the first time that nations at war turned to seaweed. During the First World War, the U.S. relied on the giant kelp seaweed (Macrocystis) to boost production of potash (a fertilizer produced in Germany), gunpowder, and acetone.

In 2007, Barrangou et al. demonstrated for the first time the function of CRISPR/Cas9 as a defensive mechanism of bacteria against bacteriophage attacks by a technique called “plaquing” which builds upon the technique of “plating” bacteria on agar. Plaques of viruses on agar are areas without growth of bacteria due to viral attacks.

The same properties also contributed to Nazi Germany’s strategy against agar’s scarcity, which — besides being supplied from Japan by submarine — relied on large pre-war stocks and on recovery methods to reuse bacteriological agar by autoclaving (boiling at around 121°C, 250°F, in a pressurized container for 30 to 60 minutes), thus liquefying and sterilizing the jelly, before purifying it again.

Koch borrowed the idea of using gelatine from mycologist Oscar Brefeld, who had used it to grow fungi. Interestingly, Brefeld also employed carrageenan, another seaweed-derived jelly. Because fungi generally favor growing at ambient temperatures, Brefeld might have been less plagued by the melting of growth media than Koch.

Julius Petri once wrote: “These shallow dishes are particularly recommended for agar plates…Counting the grown colonies is also easy.” (Translated by Corrado Nai from the original, 1887 German manuscript.)

Agarose is used in electrophoresis, chromatography, immunodiffusion assays, cell and tissue culturing, and other applications. It is the electrically neutral, non-sulphated, gelling component of agar. While its market is smaller, it is fundamental for specialized biochemical and analytical protocols.

Gigartina stella and Chondrus crispus, for example, were used as main agarophyte in Britain during WWII, alongside the use of a different colloid, carrageenan (see main text).

Washing and drying the bulk raw material to prevent spoilage also isn’t easy. During WWII, volunteers in Britain occasionally dammed natural streams to wash the seaweeds and used hot air from a bakery to dry them. Praising the concerted efforts of volunteers, the UK Ministry of Supply concluded that “all belligerent countries should have a local source” of agar.

When I was a young Masters student, I wondered why the price of molecular grade agarose was 500x that of grocery store agar. I tried taking some from my kitchen to the lab, boiled it in TAE (Tris, acetate, EDTA buffer) and tried running a DNA gel on it. The bands came out all wiggly and blurred. Not surprisingly, it's much less homogenous!

I'm curious as to how they separate out the different molecular weights/gel pore sizes of molecular biology grade agar. Is that inherent to what's being synthesized by the algae and dependent on species and growth conditions, or is there a separation process during manufacturing?

Also, the bit about agar being “standard” so it’s hard to replace feels painfully familiar. Even if you find a better material, you’re fighting protocols, comparability, and the inertia of decades of literature. The tech constraint isn’t just chemistry, it’s the ecosystem around it.