How to Scale Proteomics

A look inside Parallel Squared Technology Institute, a focused research organization trying to make analyzing a proteome as easy as DNA sequencing.

A cell is a vibrating bag of molecules, densely packed with DNA, proteins, RNAs, and lipids. The ratios of these molecules are not balanced, though. A typical HeLa cell, widely used as a model to study cancer in the laboratory, has about 20 times more protein than DNA by mass.

Such imbalances are pervasive across the tree of life, but proteins are always the heaviest and most diverse group of molecules within a cell. A single human cell encodes more than 20,000 proteins, each built from 20 standard amino acids. But those amino acids can be arranged in a staggering number of combinations to make everything from small, spindly structures like insulin (51 amino acids) to globular giants such as titin (34,350 amino acids).

A protein’s structure is not fixed, either. Chemical tags can modify it. Adding a sugar molecule to certain antibody proteins can flip whether they activate or suppress inflammation. And when an enzyme called glycogen phosphorylase is tagged with phosphate, it begins chewing up glycogen to release the glucose molecules that feed hungry muscle cells.

So, while human cells make thousands of different proteins, the forms of those proteins shift according to a cell’s needs. This vast chemical diversity is what makes proteins so adaptable. Despite their importance, however, molecular biologists rarely study proteins directly because the technology to do so is limited and does not easily scale to a large quantity of cells.

The cost to sequence a human genome fell from about $100,000 in 2009 to a few hundred dollars today. Massive sequencing machines can study thousands of genomes each day. The costs to analyze a cell’s proteome have likewise fallen over time; it now costs anywhere from $2 to $50 to study the proteins in a single mammalian cell.

However, that low cost can be misleading. Unlike genomes, which are mostly identical across all the cells in an organism, the proteins within each cell can vary considerably. To get a clear picture of what's happening in a sample, then, researchers must look at each proteome individually. Ideally, scientists would study thousands of cells in each experiment, but existing proteomics technologies can only be used to analyze about a dozen cells at once — a paltry amount.

This limitation stymies biology research, especially for diseases like Alzheimer’s, which are heavily influenced by post-translational modifications. Protein alterations, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination, can alter a protein’s function in ways that are invisible at the level of DNA or RNA. And, furthermore, it is exceptionally difficult to study the brain, with its billions of cells, by looking at just a few cells each day.

This bottleneck is what Parallel Squared Technology Institute, a non-profit research organization, is trying to solve. On a brisk day in March, I visited their laboratories in Watertown, Massachusetts, to learn about their efforts to make proteomics as easy and affordable as DNA sequencing.

Lackluster Experiments

The main technology used to study proteins, called mass spectrometry, was invented more than a century ago. Today, it is used in everything from chemical analysis to drug discovery, but it was not initially developed with biologists in mind. Rather, it originated among physicists keen on investigating the elemental nature of electricity and gases.

The first mass spectrometer was made in 1912 by British physicist J. J. Thomson, and was crafted from just three parts: a glass discharge tube in which to ionize gases and make positive ions, a cathode with a little hole through which those positive ions would flow, and a photographic plate.

Thomson’s device shot ions through electric and magnetic fields. The electric field accelerated the ions, while the magnetic field bent their paths and splattered them against the photographic plate. Lighter ions were deflected more by the magnetic field than their heavier counterparts, because they had a smaller mass-to-charge ratio; they also traveled faster, since all ions were given the same amount of energy. By tracking the pattern of ion beams on his plates, Thomson discovered a way to separate individual ions according to size and charge.

When Thomson used his mass spectrometer to study neon gas, he found two distinct spots rather than one; the first evidence for neon's isotopes, neon-20 and neon-22.

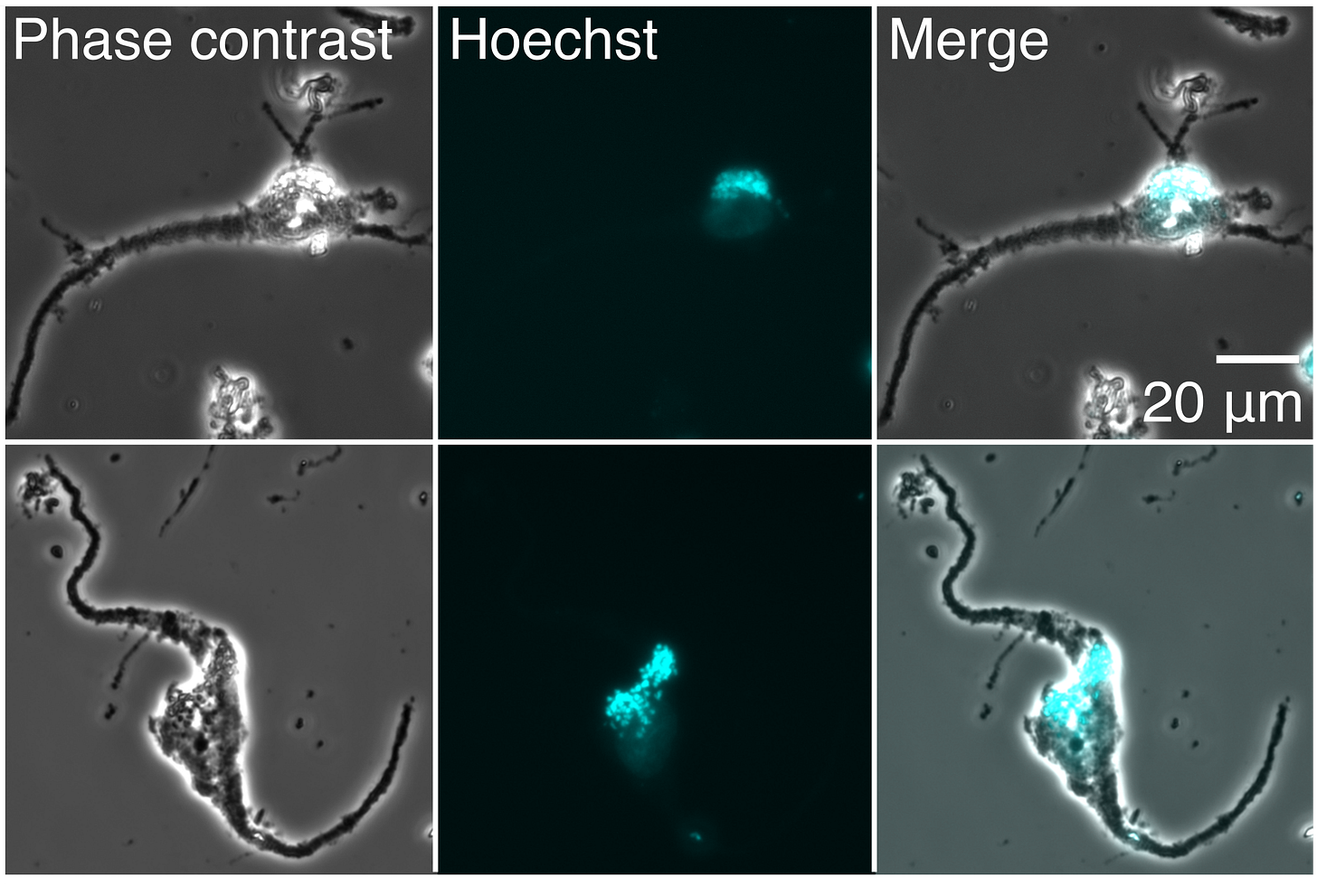

Today, mass spectrometry has advanced so much that researchers can extract proteins from individual cells to ionize for study. The technology can be used to, say, study a single neuron from the human brain.

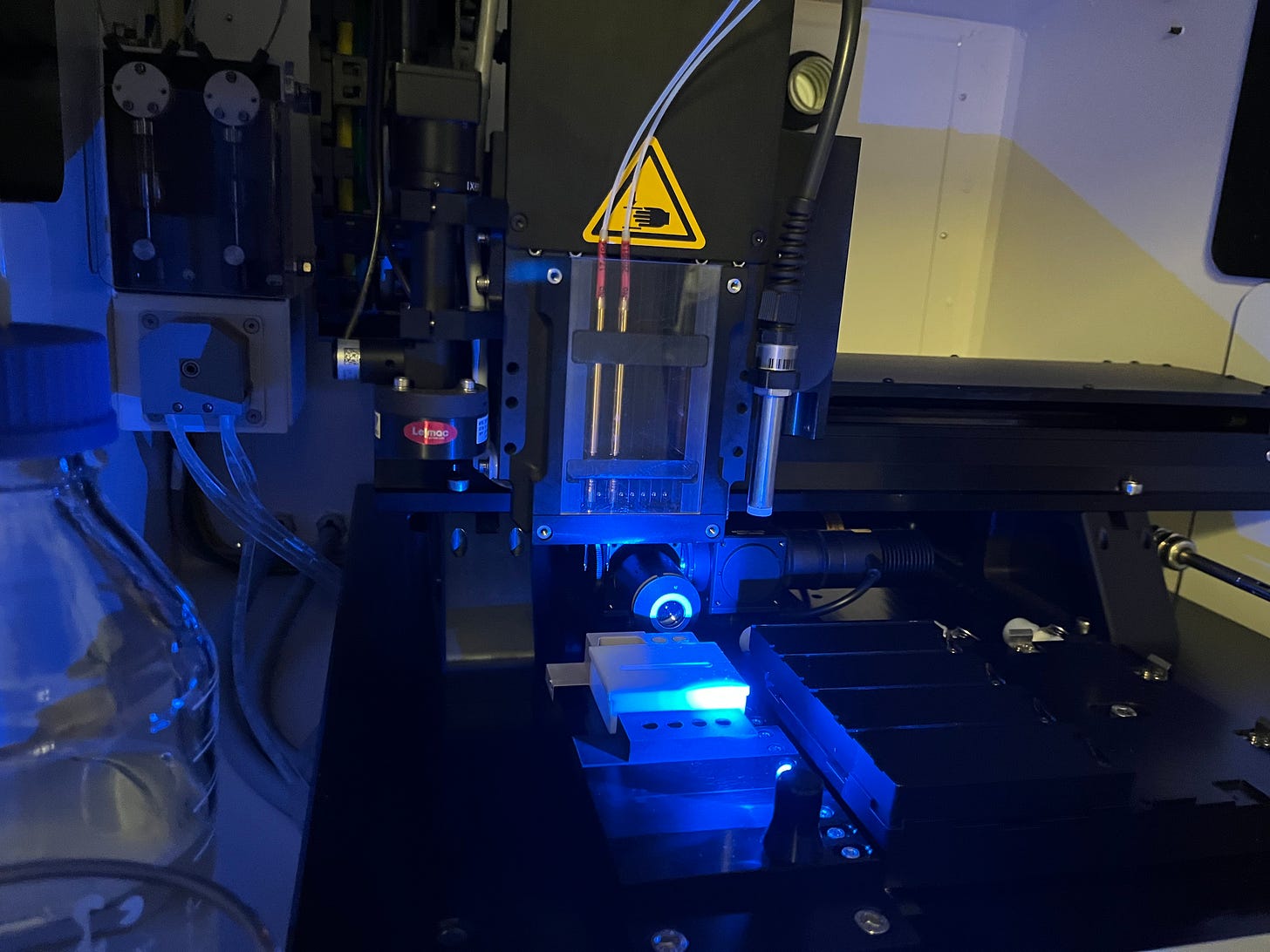

Such an experiment begins with a neuroscientist using a fine scalpel to slice out a tiny piece of a donor's brain. The brain slice is next slipped into a machine that dyes the tissue and uses cameras to map out individual cells from the stains. Each cell is excised using a laser, dropped into a container, and lysed. When each cell breaks apart, its gooey insides — proteins included — are released into the vessel.

Next, these protein-filled droplets are studied using mass spectrometry. A small molecule “barcode” is added to each droplet and attaches itself to the proteins within. (These barcodes are typically made using combinations of isotopes, such as a carbon-13 or nitrogen-15, and help scientists figure out which proteins came from which cell).

Finally, the results must be read out. The barcoded proteins inside each droplet are ionized and injected into a mass spectrometer, which separates each protein by its mass and charge. As the proteins exit the machine, they strike a detector and appear as a pattern of lines on a computer screen. The intensity of detected ions is mapped on the vertical (y-axis) and their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) on the horizontal (x-axis) of the chart, called a mass spectrum. Taller peaks indicate a higher abundance of a protein. Peaks on the right side of the chart correspond to heavier proteins.

The final two stages of this process — namely, the barcoding and data processing — are the most vexing inefficiencies that Parallel Squared Technology Institute, or PTI, is trying to solve.

Many Cells, One Machine

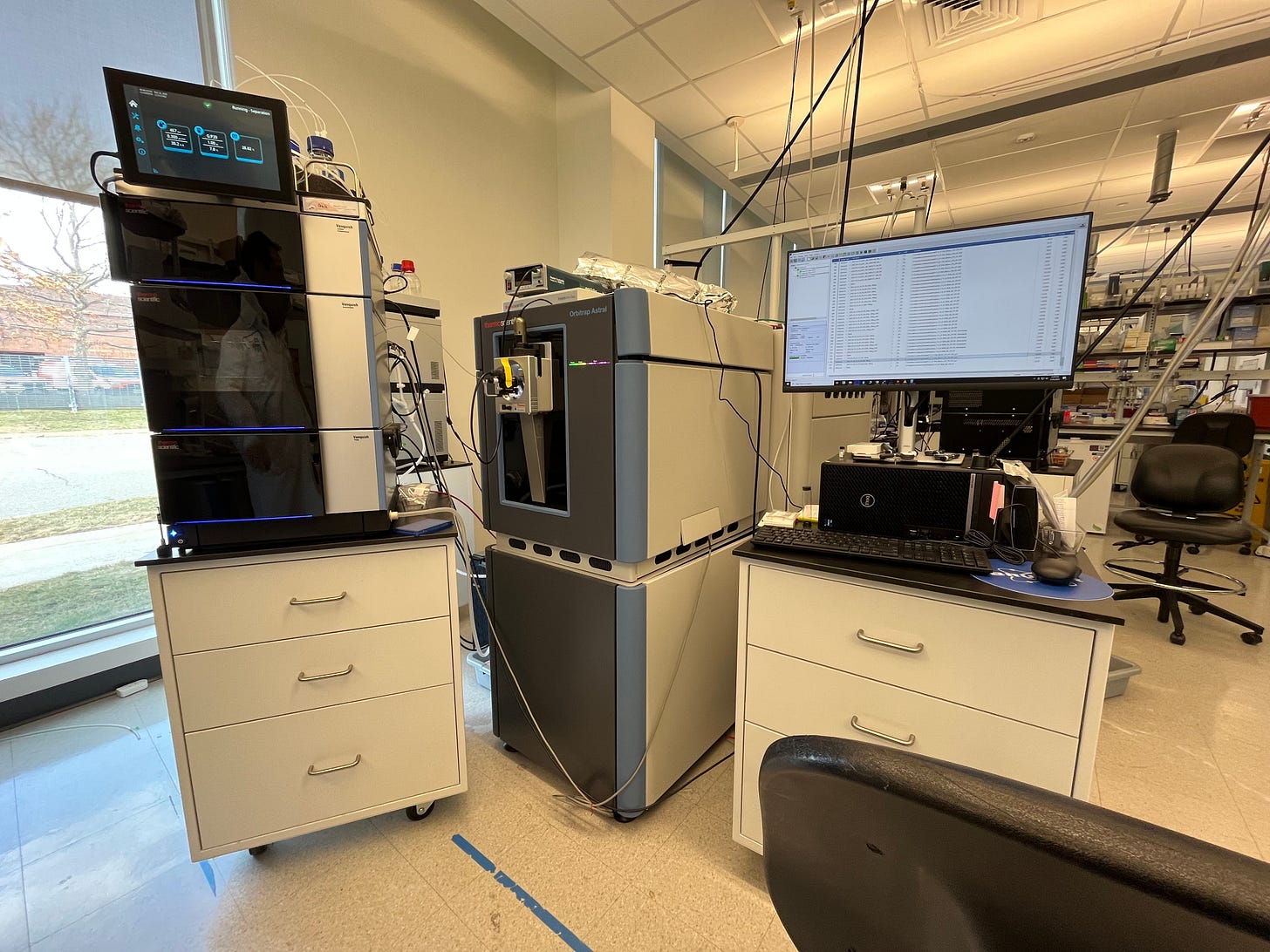

PTI occupies one half of a squat, glass-and-steel framed research facility in Watertown, Massachusetts. (The other half is occupied by Cultivarium, another non-profit research organization that I have previously covered for Asimov Press.) PTI’s laboratory is quite spacious. Instead of a clutter of experimental tools, like you might find in a standard molecular biology lab, the space is sparsely filled with machines to isolate cells, a handful of mass spectrometers, and computers to process data.

The organization traces its origins back to 2020, when Adam Marblestone, CEO of Convergent Research, first approached Nikolai Slavov. At that time, Convergent had already identified proteomics as a technical area with the potential to unblock many downstream R&D breakthroughs. And Slavov, a professor of bioengineering at Northeastern University, seemed like an ideal person to help make it happen.

Slavov’s group was already building methods to scale single-cell proteomics at that time. His group had published influential reviews laying out roadmaps for progress. Around the same time, his laboratory invented a method capable of quantifying more than a thousand proteins at once in individual mouse stem cells. Marblestone asked Slavov if his ideas to scale proteomics might benefit from a focused research organization structure; Slavov said it would.

After a few years of planning and fundraising, PTI launched in 2023. It was co-founded by Slavov, together with Harrison Specht and Aleksandra Petelski — two researchers from his laboratory at Northeastern University.

Today, the team includes 22 people across biochemistry, computational biology, and organic chemistry. Their overarching goal is to build proteomics technology that can be used to study thousands of cells at once without building better hardware. Their strategy has three parts: make better barcodes, devise functional protocols to get more out of mass spectrometers, and write advanced software to handle all the data.

Let’s start with the barcodes.

Right now, there are only about a dozen unique barcodes that scientists use in proteomics. This means that it’s only possible to study a small number of cells on a machine at any given time. On a given day, a scientist working around the clock might be able to study the proteome of 100 individual cells. At this speed, it would take about a million days to map the proteome of each cell in the human brain with existing technology.

It’s also difficult to make new barcodes because the signals from each sample start to overlap. Some barcodes also change the properties of the proteins to which they bind, causing them to ionize less easily. Prior to PTI, there was no way to systematically explore the vast permutations of all possible barcodes.

Sensibly, the PTI team was not satisfied with this.

Their solution is to brute-force the chemistry, collect lots of data, and then apply learning approaches to discover how to design better barcodes. Their chemistry team aims to make hundreds of thousands of different barcodes, and has already screened 10,000 so far this year. Each barcode has a “hook” so that it can easily grab onto proteins. And each protein, once barcoded, runs through the mass spectrometer.

Next, a data team looks at which barcodes generate brighter signals or change how the proteins move through the mass spectrometer. The data from each experiment is fed into computational algorithms, which will later help PTI’s analysis teams design barcodes in a more rational way.

So far, PTI has made a 9-plex barcode system, meaning they can deconvolute nine different proteomes in a single experiment. The prior state-of-the-art was just three barcodes.

At the end of the day, though, even this is not enough. Scaling single-cell proteomics experiments to thousands of cells will demand more than just barcodes. That moves us to PTI’s second innovation — a proof of concept approach to get more data out of mass spectrometers.

Historically, the speed of mass spectrometry was constrained by how quickly proteins separate according to their mass and charge. In many cases, scientists must wait 30-60 minutes for a batch of proteins to move through the machine before they can load another sample.

But PTI has figured out a way around this start-and-stop limit, using a method called timePlex.

Instead of loading samples into a mass spectrometer and then waiting for the whole experiment to finish, they instead feed three batches of samples into one instrument, offsetting each injection by a few minutes. The result is a single, continuous stream of signals: a set of barcoded cells goes in first, a second batch a few minutes later, then a third, and so on. Because each sample enters the machine with a slight delay, its signals appear at predictable intervals, effectively multiplying throughput without new hardware. PTI has done experiments using 9 barcodes and 3 offset loads at once, meaning they can effectively do a 27-plex experiment.

The overlap between samples complicates data analysis, however. A small peptide from the second injection can exit the machine and strike the detector at the same moment as a large peptide from the first, thus blending their signals. PTI handles this complication by logging the exact start time of every injection and then using custom-made software to assign each detected ion to its most likely source. The program tracks retention time, mass-to-charge ratio, and each barcode tag, and then disentangles overlaps and down-weights ambiguous data.

If you combine the barcodes with timePlex, PTI has effectively already boosted the number of proteomes scientists can study in a single day by an order of magnitude, relative to prior state-of-the-art methods. And they’ve only existed for two years! Now they plan to scale this up by another 100x, at least. And if they succeed, it may be possible to profile the proteome of every cell in the human brain in the span of a few years; a feat likely to have an enormous impact on our understanding of complex diseases.

Alzheimer’s and Beyond

From the beginning, PTI has been using their technologies to study Alzheimer’s, a progressive form of dementia that afflicts about 7.1 million Americans and seems to be driven — in part — by proteins.

Scientists have already sequenced the RNA molecules of millions of brain cells from people with Alzheimer’s. Those datasets are useful but just a draft; they miss most protein-level events, including those that turn healthy Tau — a protein that stabilizes the internal structure of neurons — into the hyper-phosphorylated tangles that define late-stage Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s is actually linked with at least two proteins: amyloid-β plaques residing outside of neurons and phosphorylated Tau proteins inside of neurons. Clinicians usually track the progress of the disease by measuring biomarkers in the blood or spinal fluid, such as phosphorylated Tau or a protein called neurofilament light (NfL). There are also two FDA-approved antibodies — lecanemab and donanemab — that have been shown to reduce plaque loads and slow cognitive decline by about 27 percent and 35 percent, respectively, over an 18-month trial window. But there are no medicines as yet that significantly lengthen the lifespan of patients with Alzheimer’s.

Unfortunately, current medicines can only be given after a patient has noticeable Alzheimer’s symptoms. But PTI believes that, by reading out the proteins of cells taken from patients with Alzheimer’s, perhaps they can learn to identify biomarkers before symptoms appear at all. Here is their approach:

First, they map the proteomes of individual neurons taken from Alzheimer’s patients who died at various stages of the disease, from Braak 0 (early) to Braak 6 (late). The scientists cut out thin sections of brain tissue and dip them into a chemical to lock each protein’s shape. This tissue is then broken into single neurons, which are sorted into tiny water droplets. Heat and a chemical solvent then bust open the cell membrane and release the proteins into each droplet. Each droplet is barcoded and passed through the mass spectrometer. And because each neuron is tagged with its Alzheimer’s stage — from Braak 0 to 6 — PTI can basically line up healthy and diseased cells and watch how specific protein quantities change as the disease progresses.

By measuring each neuron’s full set of proteins, the PTI team hopes to find warning signs long before plaques or tangles are obvious. Their goal is to flag markers that show up in the disease’s quiet, prodromal phase, when treatments have a better shot at working. Also, early data suggest that what we call “Alzheimer’s” might actually be a multitude of molecularly distinct diseases, each with its own modifiers, and perhaps these various multitudes could be seen in the proteomics data.

The team’s main limitation is throughput. Currently, the team's single-cell preparation robot — which cuts the neurons out of brain tissue — can keep up with the mass spectrometers. But as their barcodes and timePlex methods expand by orders of magnitude, the mechanical parts of their experiment will begin to lag behind. The main bottleneck will move from mass spectrometry to sample preparation. With a firehose of single-cell data, though, PTI aims to quantify proteomes of every single cell type in the human brain across Alzheimer’s progression.

But Alzheimer’s is just a starting point. With full protein maps for every cell type, researchers could also trace how signaling circuits misfire in cancer, follow immune cells as they learn to recognize pathogens, or spot early shifts in brain disorders long before symptoms start.

When single-cell proteomics becomes as routine as DNA sequencing, molecular biologists will finally be able to fully celebrate — and understand — the centrality of proteins in the workings of our cells.

Niko McCarty is a founding editor of Asimov Press.

Cite: McCarty N. “How to Scale Proteomics.” Asimov Press (2025). https://doi.org/10.62211/29ur-44hf

Reporting for this article was made possible by Convergent Research. Thanks to Rachel Krasner, Harrison Specht, and Joseph Fridman for reading drafts of this. All mistakes are my own.

Lead image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Interesting article and interesting company! Single cell proteomics is indeed hard, largely do with the vast concentration range of proteins w/in a cell - much easier task if millions of cells are pooled. DNA scientists are fortunate to have PCR which will exponentially amplify target from minimal template - proteomics scientists have no such luxury. The other major difference is that proteomics sequencing efforts are not "de novo", meaning that the sequences must match a reference database in order to be identified in the experiment. That falls short when the goal is detecting variant proteins. There is a new DARPA program focused on the development of better "sequencing" methods for proteomics (https://www.darpa.mil/research/programs/protein-sequencing-prose) which promises large investment. I am excited to see how that develops.

Interesting article. Naive question: Is there any possibility that the transcription factors of gene regulation could be determined during DNA sequencing? If you know which genes are turned on then you would know which proteins are being produced. Any possibility nanopore sequencing, or a specialized variant, might possibly pick off the regulatory proteins as DNA passes through the pore?