Brazil’s Mosquito Factory is Supposed to Curb Dengue. There's A Better Way.

If you want to kill mosquitoes, sometimes you gotta make more of ‘em.

A massive mosquito factory is under construction in Brazil, according to a recent article in Nature. My initial reaction — huh? — quickly gave way to intrigue, which soon morphed into confusion. Many folks have already commented on the news, but nobody has said this: This mosquito factory will be outdated as soon as it’s completed.

The factory will produce up to five billion mosquitoes each year, each of which will be infected with a bacterium, called Wolbachia. These infected mosquitoes (all Aedes aegypti) will be released in cities across Brazil; they’ll breed with their wild counterparts and pass the microbe to their offspring. Mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia have a reduced ability to transmit viruses to people. Cases of dengue and Zika will slowly fall.

At least, that’s the goal.

The World Mosquito Program (tagline: “Releasing Hope”) is behind the Brazil factory. They’ve already carried out controlled releases of Wolbachia mosquitoes in Indonesia and Rio de Janeiro. Those trials showed a 77 percent and 38 percent drop in dengue cases, respectively, but similar projects have failed elsewhere. During trials on a Vietnamese island, Wolbachia mosquitoes were released and then entirely vanished for reasons that we still don’t fully understand.

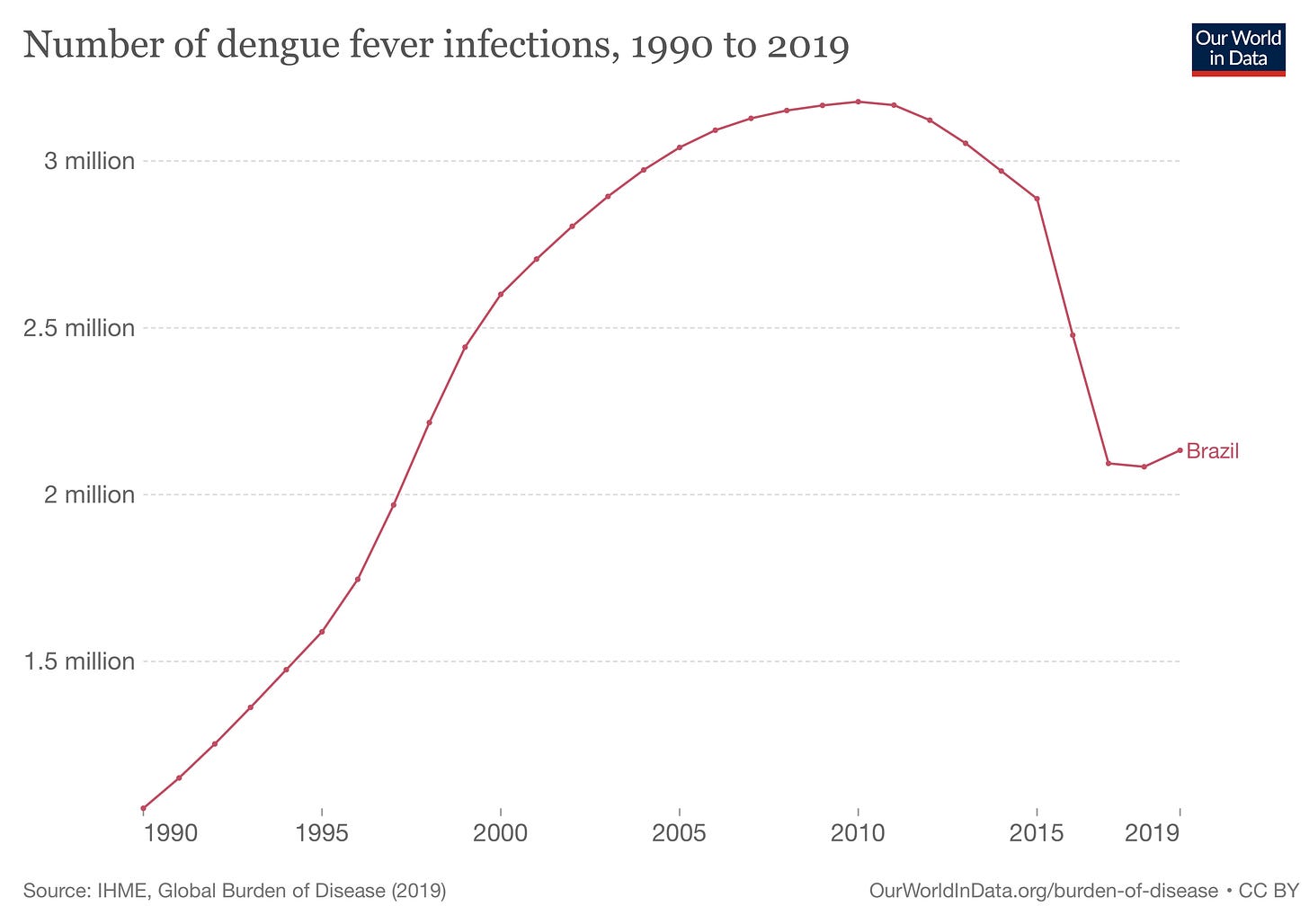

Still, any drop in dengue is a success. Mosquitoes kill something like 700,000 people each year. In just the last five years, 481 municipalities in Brazil “detected community dengue transmission for the first time, accounting for 8.7 million new individuals at risk,” according to a recent study.

Despite the World Mosquito Program’s mixed success, the Wolbachia approach is flawed for many reasons: Its effectiveness varies widely from one climate to the next; released female mosquitoes still bite people; and Wolbachia can possibly spread to other types of insects and harm their populations. We have better ways to control mosquito-borne diseases, but only if we embrace gene-editing.

To understand these “better ways,” though, we first have to understand how workers at the Brazil factory will breed and release mosquitoes, and why it’s problematic. The World Mosquito Program (which is partially funded by the Gates Foundation) already operates a smaller factory in Medellín, Colombia that makes about 30 million mosquitoes each week.

It works like this: First, you take a bunch of mosquito eggs and infect them with Wolbachia. After a few weeks, you take the infected females, throw ‘em in a cage (with the temperature set to at least 27 degrees Celsius, and humidity at more than 75 percent), and let them mate with uninfected males. If you’re strapped for cash and don’t want to build a custom sweat box, there’s an easier way: Take a small electric light bulb, place it in the cage, and then drape a wet towel over it. (Good enough!)

Mosquitoes can survive on little more than live rodents (or just bags of blood donated by a slaughterhouse) and sugar water. After two days of mating, the females lay about 200 eggs each. Larvae hatch in 6-12 hours and can reproduce within 7 days. It’s theoretically possible to make about 10 billion mosquitoes from a starting batch of 100 females in as little as two months.

Once the mosquito factory has made all these insects, they are packaged into boxes or cups and then released in “strategic” areas within a city, like near swampy water or in dengue-ridden neighborhoods.

Now for the catch: The Wolbachia approach is flawed because females (the only sex that actually bites and transmits the microbe) are released along with the males. Many of them will bite people. The infected insects also vary massively in their fitness levels; some of them are quite healthy, while others aren’t strong enough to breed in the wild. Of the five billion insects the new factory releases yearly, only a fraction will actually “do their job.”

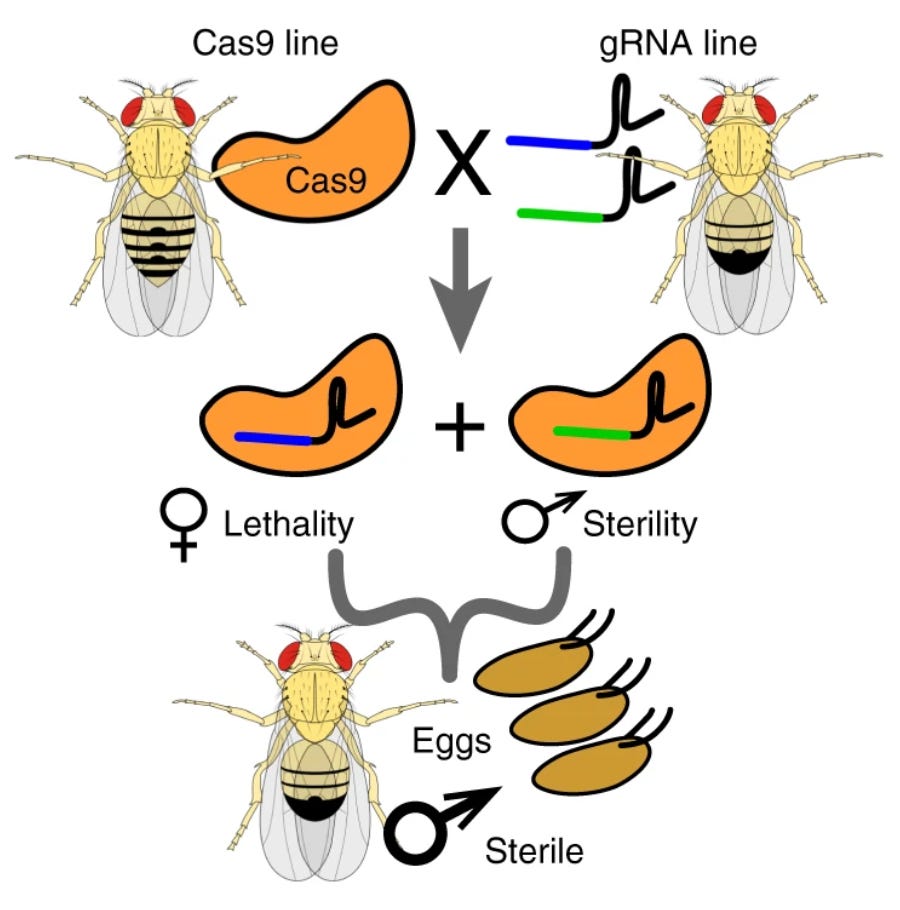

A new method called the precision-guided sterile insect technique (pgSIT), solves many of these problems. To use it, mosquitoes are bred in exactly the same way that I’ve already described, but with one major difference: Instead of infecting females with a bacterium, they are genetically engineered to express the Cas9 protein (one part of the CRISPR system), while male mosquitoes are engineered to express guide RNAs.

When the insects mate, their offspring inherit both the Cas9 and the guide RNAs. These molecules come together, stick to mosquito genes, and cleave them in two. The broken genes don’t work anymore.

Here’s the clever bit: The guide RNAs are specially designed to target two genes in particular; one for female survival and another for male fertility. When a gene-edited female lays her eggs, then, the female offspring never hatch, while the males hatch but cannot produce offspring of their own. (In males, the guide RNAs chop up a gene called beta-tubulin, which is required for sperm to swim.)

In other words, pGSIT makes it possible to eliminate biting females and render males sterile in one fell swoop, without adding any time to the normal mosquito breeding program. This technology isn’t a gene drive; the CRISPR components don’t pass from one generation to the next, because only the males survive, and the males can’t make children.

It has other advantages, too. CRISPR works in just about every living thing on the planet, so pgSIT can be used in many different insects, including Aedes aegypti (which spreads dengue and Zika), Anopheles gambiae (which spreads malaria) and Drosophila suzukii (a pest that lays its eggs in peaches, strawberries, and grapes.) The Wolbachia method is not as versatile.

Now, I’m not gonna sit here and try to convince you that this method is perfect. Nothing ever is. The method hasn’t even been tested in the real world as far as I know, and experiments in the lab suggest that you’d have to release a lot of these mosquitoes (perhaps 10 gene-edited mosquitos for every one in the wild) to make a sizable impact. But the technology has already been licensed to a crop pest control company, called AgraGene, and initial experiments in the lab seem promising.

Still, it will be difficult (but certainly not impossible) for the technology to earn regulatory approval, because gene-edited mosquitoes sound like a plot point in a sci-fi horror movie.

Oxitec, a British company that uses a similar technology to control mosquitoes, has already released their transgenic insects in the Florida Keys, Brazil, and elsewhere. But it took years for them to get EPA approval, because nobody in government had any idea who should regulate this niche technology. Oxitec’s technique works really well, though: In dengue-prone neighborhoods in Brazil, it caused a 96% reduction in the mosquito population. (The company’s technology does not rely upon CRISPR-Cas9 but does require that mosquitoes be fed a specific antibiotic during breeding. This suppresses their immune systems and probably makes them less fit in the wild.)

I can’t predict the future, or tell you what will happen with Brazil’s new mosquito factory. But I do know this: Genetic engineering has endowed us with a radical ability to control our environments. It can be used to decimate insects to a degree that has never been possible in the course of human history. A mosquito may have killed Alexander the Great, but soon, disease-carrying insects could be no more.

Vanquishers will become the vanquished.

Thanks to Nikolay Kandul for helpful discussions.

Note: Only female mosquitoes can transmit Wolbachia to offspring, and this is why the World Mosquito Program releases both sexes. I still think the pgSIT approach would streamline breeding and generally work better.

Disclosure: The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not represent the views of any company or university with which I am affiliated.

Niko, please don't laugh and also consider my plea that I all I know about gene editing , CRISPR and biology can be fitted into a teacup, but... Maybe, just maybe we don't want to eliminate ALL the mosquitoes or even a substantial fraction!? I think mosquitoes are a pretty useless group in general, but perhaps these little flying hypodermics act as gene transfer agents that somehow enhance evolution? Could that be true? I dunno. I just have this vision of some not so intelligent hominid ancestor of ours getting bit by a mosquito and voila, us!

So cool! Thanks for this piece!