News fitting to the night,

Black, fearful, comfortless and horrible.— Shakespeare, King John

Only a handful of books and essays have ever made me cry. John Hershey’s “Hiroshima” and Atul Gawande’s “Letting Go,” both published in The New Yorker magazine, made me sob.

Neither article is beautifully written, nor filled with poetic prose and clever turns of phrase. Both are simple and plain in text, but nuanced in structure. They hide just enough information to keep you reading, and then reveal details at just the right times to eviscerate your emotions. Both articles draw upon the authors’ personal experiences, and this lends them their power.

Consider Hiroshima, a 31,000-word account of the atomic bomb that fell at 8:15 am on August 6th, 1945. Hershey tells the stories of six survivors and recounts precisely what they were doing before and after that seminal moment. His writing is flat and unemotional, but also filled with horrifying visions: Melted eyes, vaporized flesh, and walls etched with shadows.

In the last few decades, writers like Hershey and Gawande have become rarefied indeed. The era of great science reportage — when writers went out and experienced the news — has ended. Science journalism, today, is sterile and formulaic. News articles rarely draw upon personal experiences. Reporters almost never visit laboratories to witness experiments firsthand.

And now, with AI, the slow death of mediocre journalism is set to accelerate. But a renaissance in science writing is poised to follow.

The Los Angeles Times, the Associated Press, and Forbes already automate some news stories. In 2014, a news writing algorithm, called Quakebot, published a story about the L.A. earthquake just 3 minutes after the ground stopped shaking.

Automated journalism has historically been confined to fields like finance or sports, where scores and numbers are simple to weave into a boilerplate template (Dow is down 2 percent! Liverpool beat Manchester United 7-0!). But it’s now profoundly simple to do the same for science.

On a recent weekday, it took me just 9 minutes to write a news article about a scientific paper in Nature magazine. At first, this AI-powered feat made me feel sad — journalism layoffs will ramp up (indeed, they are already here) and I suspect we’ll see a sharp uptick in content farms. But mostly, it made me happy, because scientists with deep knowledge and unique insights now have the incredible power to remove journalists as gatekeepers.

People will grow tired of content farms in a couple of years, but they will never tire of first-hand accounts. The science news outlets that thrive will be those who send reporters out into the world, and the writers who “make it big” will be those who tell their own stories, on their own terms.

The Bad News

For every Ed Yong, there are twenty others who write like robots.

If you have a moment, go to nature.com and pick out a recent research study (like this one, in which engineered proteins were used to “inject” gene-editors into living cells.) Now, look at the news outlets that covered the paper by clicking on the “Metrics” button (this particular paper was covered by 47 websites.) Most of the coverage, I’d wager, uses identical quotes, copy-pasted from a press release, and presents eerily similar information as all the others. I’ve blogged about this phenomenon before.

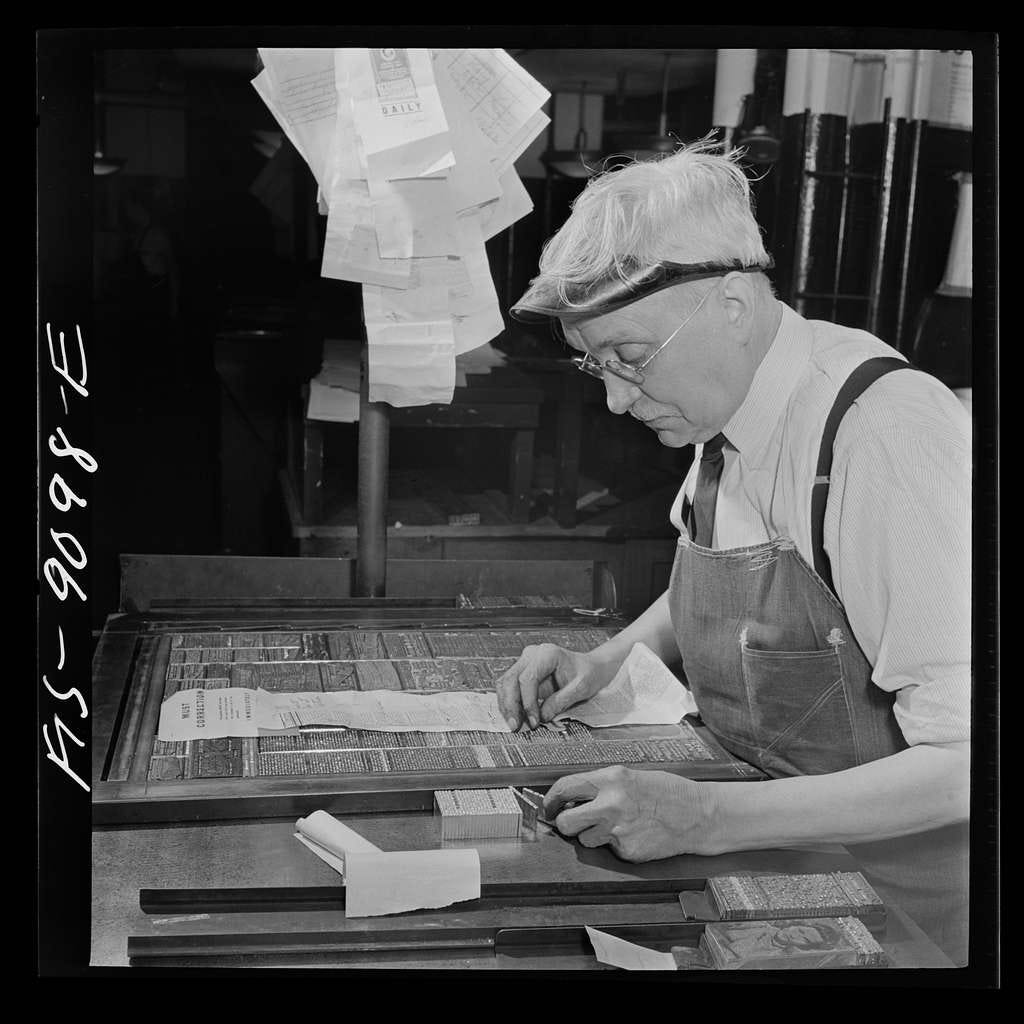

There is a historical reason for homogenous news coverage: Before computers, newspaper pages were physically laid out using typesetting, in which editors arranged metal letters, called type, in a frame. These frames were then inked and pressed onto paper to print the text.

If an article’s text did not fit within its designated spot on the page, editors took drastic action: They physically cut articles to an appropriate size. Writers, accordingly, learned to move all the riveting bits of a story to the very top. Headlines evolved to become more descriptive, and introductory paragraphs became loaded with details like who, what, and why.

To this day, news articles follow the basic structure that was first honed in the typesetting era. This “news formula” is the first thing they teach you in journalism school. If you master it, you could quite easily quit your day job and become a freelance writer, or at least a Substack blogger (though I don’t recommend either.)

The structure for science news goes something like this:

Lede: The first paragraph; quickly explains the “thing” that happened (Experts say AGI will replace all humans!), along with the what, why, and who.

Nut Graf: Often the second paragraph, it explains why a reader should continue scrolling, often by teasing some broader implications of the work.

History: A couple paragraphs in length, the history section explains the prior state-of-the-art. What did scientists think or do before this study was published? How does the new paper improve upon everything that came before?

Methods: How did the scientists build the fancy new algorithm, or launch a satellite into orbit? How many undergraduate students surrendered their souls in the process?

Conclusion: Most articles end with a futuristic outlook: “This study changes everything,” said the professor who folds paper airplanes. “I’m buzzing at the possibilities!”

(Optional) Mix in some quotes to imbue the article with a rarified air of importance. Quotes signal that you are an important reporter: Just look at all the fancy professors with whom I’ve spoken!

Most news outlets follow this basic template. GPT-4, the new AI model from OpenAI, can already match many human reporters if the tool is prompted to write each section, one at a time. (Ask ChatGPT to write an entire news story at once, and its output will be repetitive and error-laden.)

Let’s look at a brief example.

On April 27th last year, an article in Nature reported an enzyme — designed using machine learning — that could break down PET plastics. It was a good paper, and I wrote about it on this blog. Many news outlets also covered it, including Chemistry World, AI Business, and Yahoo! A large chunk of the news coverage sounded quite similar, and more than a dozen articles re-used quotes from the same press release.

So naturally, I was curious: How fast could I get ChatGPT to write an article “on par” with the ones in AI Business or Yahoo? The answer was 9 minutes.

(Ethan Mollick, an associate professor at Wharton Business School, recently wrote an essay in which he used AI tools to design a product, plan a marketing campaign, write emails, build a website, and then write social media posts across platforms in just 30 minutes.)

To write the news story, I prompted ChatGPT to write one section at a time (just the lede, or just the nut graf) and “fed” the AI with appropriate passages from the paper. (The lede of a news story is often just an adaptation of a paper’s abstract, whereas the “history” section of a news story is often a rehashing of a paper’s introduction.)

All of my prompts and associated outputs are available here.

After prompting ChatGPT to write each section, I then asked it to weave everything together, and also to incorporate quotes from a press release. The final output is provided below. Individual sections and errors are highlighted.

The output was impressive; comparable to most news outlets that wrote about this paper. The AI even integrated quotes in suitable places. My brief experiment suggests that content farms are coming. Young writers who sit in cubicles and draft soulless news articles, based solely on press releases, will get sacked.

But just about everyone else will flourish. The good will far outweigh the bad.

The Good News

In a few years, we’ll see a resurgence in great journalism, because the writing that will stand out most will be those stories that draw upon deeply personal experiences. Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at New York University, has opined on the “authority of the journalist” before, and his takeaways are clear: The key to credibility is specificity.

From Rosen:

The authority of the journalist originates in this kind of claim: “I’m there, you’re not, let me tell you about it.” Or: “I reviewed those documents, you couldn’t—you were too busy trying to pay the mortgage—so let me tell you what they show.” Or: “We interviewed the workers who were on that drilling platform when it exploded, you didn’t, let us tell you their story.”

AI tools can’t go to board meetings (yet) or interview workers on a drilling platform. But humans can, and their lived experiences will not be replaced.

Consider scientists and physicians. The former performs experiments and generates data that exist nowhere else but their mind, and a lab notebook. The latter treat real patients and possess firsthand accounts of science applied to the human experience. An AI cannot emulate either.

In other words, scientists and physicians are the future of science writing.

Atul Gawande is a practicing physician, who happens to be a writer. He infuses his articles with personal experiences and stories of real patients. Siddhartha Mukherjee is a physician and scientist who happens to be a writer, too. And Stephen Jay Gould was an evolutionary biologist who taught at Harvard and New York University, and who happened to be a writer who wrote 300 essays for Natural History magazine.

It is no accident that the greatest biology writers of our generation were those with unique insights and viewpoints. If you are a scientist or physician who yearns to write but doesn’t “have the time,” what is stopping you now? I’ve given you the basic structure of a news story and shown you how to automate almost everything with AI. If you’ve been waiting to write, now is the time to pick up the mantle and claim your place as the next Mukherjee or Gawande. AI tools will accelerate your work, but they will never replace your perspective.

A handful of scientists are already blogging about their scientific ideas in public. Erika DeBenedictis and Sam Rodriques, both at the Crick Institute in London, write popular Substacks and have rightly garnered a lot of praise. Everybody wants insights into how science is done, and scientists now have a generational opportunity to make their work public and accessible to others, without relying upon journalists.

In the next few decades, I suspect (and hope) that there will be dozens of Stephen Jay Goulds. We need more communicators to convey the beautiful things that are happening in biology, from gene-editing advances to lifesaving medicines.

I know we can build this future together.

Rebirth

When SARS-CoV-2 landed in America, I clicked ‘send’ on an application that cemented my transition from science to writing. At the time, I knew nothing of AI (and still know so little). But I looked back at my application the other day, and was surprised that many of its points were an early reflection of this very essay:

“During my time in London,” I wrote, “I began to see research and writing as two sides of the same coin. My strength as a writer and storyteller would not be possible in the absence of scientific experience, because the skills that I use to investigate natural phenomena and interpret data are the same ones that I use when honing a story and vetting a source.”

The application was a success. I moved to New York and enrolled in journalism school. I learned the dark arts of writing. Even today, I consider myself a writer first and scientist second. But with the rise of AI — and ceaseless discourse on Twitter, where everyone acts like an expert and it’s impossible to go a single day without reflecting on my future relevance — I would be lying if I said that I didn’t worry about the years ahead.

It’d require zero effort for me to sit at my desk, paralyzed, and cower in fear at my future obsolescence. I could nervously track AI’s progress, throw away my Substack, and become resigned to my fate as a wannabe writer who never achieves the literary acumen of a John McPhee or Siddhartha Mukherjee. Or, I could pore over the latest job report from OpenAI — which says that “100 percent” of writers will be impacted by new AI tools — and hide beneath my desk.

But AI has not made me do any of those things. I’ve never curled into a ball, or cowered beneath my desk. Instead, I am embracing opportunity, in this strange era, over disillusionment.

The writers who inherit the world will be those who grab you by the skull, shake you by your soul, and paint the world through vivid, vulnerable prose.

The future will be told by the writers who make you cry.◾

— Niko McCarty

Niko, don't underestimate Gen Four's ability, with suitable prompts to produce realistic "I was there at the scene-here's my personal and emotional reporting" type content (whew, let me catch my breath from such a long sentence!). The looming crisis is one of epidemic uncertainty and deep fakery..

In fact Gen Four could have produced my remarks here, including exclamation marks, humorous asides and warnings about itself.

But it didn't I assure you.

See what I mean?

At the start of your article, you talk about how journalists can withhold information or provide information in order to maximise the emotional effect on the reader. Do you think it would be possible for AI to achieve this purely through a knowledge and application of neurology / psychology? For example, we know about certain things which often increase levels of dopamine - could AI use this knowledge to move readers emotionally?

Thank you for a very interesting article :)