Codon Digest: Seeing Colors After Gene Therapy

Plus: Memes, growing rat neurons to play DOOM, and Nobel Laureates are less productive.

This is Codon Digest, a monthly roundup of progress and ideas in biology. ❤️

Note from our sponsor:

At Codon, we love tools that help biologists move faster. Primordium Labs will sequence your whole plasmids overnight for just $15, no primers needed. Faster, cheaper, and less hassle. What's not to like? Start sequencing.

My recent essay with Julian Englert is about a protein printer that could (theoretically) convert digital bits into physical atoms. Thank you to those who read it and left comments. Some highlights:

My friend Daniel Goodwin tells me that light-controlled proteins are remarkably slow to control. It could take many seconds to move the ribosome from one codon to the next, and so our hypothetical device might take hours to make a single protein.

Alex Reis asks if proteins produced with this method would fold properly. I’m not sure. Light-controlled protein synthesis is a sketchy technology, and a protein made slowly may not fold in the same way as a protein made quickly. A ribosome in a human cell adds five amino acids to a protein chain each second.

Max Berry left an excellent comment. I could write an entire article in response, but if you want to go deeper into this subject, I suggest you read it in full.

Gene-edited trees. For a recent study, researchers edited 21 different genes in poplar trees, a species commonly used to make paper. Separating cellulose from lignin — a key step in the paper-making process — emits about 150 million tons of greenhouse gases each year. By reducing the amount of lignin in wood, it is easier to get out the cellulose, and these emissions go down. The researchers studied trees with 70,000 different gene-editing combinations, just 0.5% of which had reduced lignin levels and extra cellulose. From an article in Science: “After 6 months, the most promising varieties had their lignin content reduced by 49.1% and their cellulose-to-lignin content increased by 228%. If a typical paper mill used these varieties, the team reports, it could increase its paper output by 40%, cut its greenhouse emissions by 20%, and boost its lifetime profits by about $1 billion.”

Gene-edited poplar tree stems appear red. The lighter stems are from wildtype poplar trees. From Sulis D.B. et al. in Science. CNGA3-achromatopsia is a hereditary disease that causes people to see in shades of gray. Their cone cells, which are responsible for color vision, don’t work like normal. But what happens if you restore these cone cells, using gene therapy? Will they start to see in color, or will their brain be unable to handle the new sensation? This study injected a viral vector, carrying a healthy copy of the CNGA3 gene, into four people; three adults and one child. One eye was treated for each person, and the other left untreated. Each person said that their vision was different after the injection, but not in a dramatic way. They weren’t able to see slight differences between colors, such as blue versus green, but all of them could kinda see the color red. Two of them could also see yellow, and one person saw all three colors. Interestingly, when asked to describe the color red, “they often admitted that they had no appropriate words to describe it,” the study says. “When encouraged to find the exact wording, they said it glows differently, shines, or appears on a different plane than the background.”

There’s a TV show where a bunch of doctors are walking through a hospital corridor. They’re talking about a patient who has a rare genetic disease. They’ve just finished sequencing the patient’s genome, but they don’t have “DNA sorting” software. So, instead, they print out the patient’s entire genome and sift through it, by hand, to find the culprit gene. It’s hilarious, even if the premise isn’t too distant from how old-school geneticists used to operate. Unfortunately, the stack of paper shown in the TV show is about 30x shorter than the actual human genome. And that’s how I learned that there are published books that contain entire chromosome sequences.

Also, the Wellcome Collection in London has a complete, printed copy of the human genome. It fills up an entire bookcase!

I wrapped up my series on “30 Days of Great Biology Papers.” This was a series of tweets in which I told brief stories behind seminal papers, mostly in molecular biology and biophysics. You can read all of them here. A big takeaway from this exercise, for me, is that nothing is inherently obvious. I often wrote about papers that are extremely well-known, such as PCR and early papers from Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner. I assumed, falsely, that few people would care about these papers because they are already taught in school. But I was wrong. Those papers had the highest engagement.

A perennial dream of bioengineers is to make enzymes that break down plastic. It’s kinda like the holy grail of biology. Imagine if you could just dump all your plastic bottles in a dishwasher-looking machine at home, and enzymes inside then broke them down and recycled them. I wrote about one of these enzymes last year, when a group in Texas used machine learning to make a PET-degrading enzyme, called FAST-PETase, that could break down a pre-heated water bottle in about two weeks at 50ºC. That’s quite slow, unfortunately, and these enzymes also leave behind a mixed bag of chemicals. They don’t always break down PET into a form that is easily recycled. But for a recent paper out of Nanjing, China, researchers engineered another enzyme and showed that, when mixed with FAST-PETase, the two worked together to break down plastic twice as fast as the Texas enzyme alone. Together, the enzymes also produce much purer terephthalic acid, which can be recycled into new plastics.

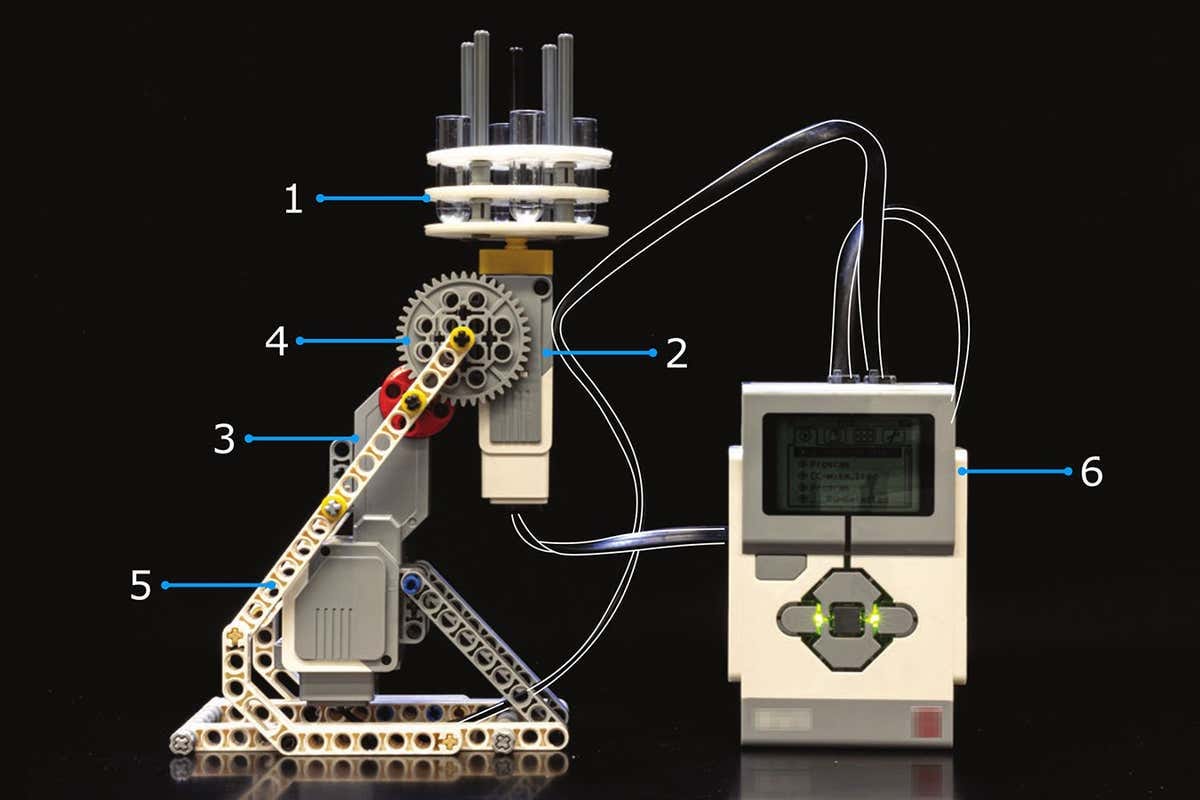

A LEGO robot, made by undergraduate students at Arizona State University, pours sucrose gradients (a tube with dense liquid at the bottom, and less dense liquid at the top), which are used to separate, say, proteins from RNA by spinning them really fast in centrifuges. This robot joins a rich lineup of LEGO lab devices, including a microscope, liquid-handling robot, and cell printer.

LEGO robot to make sucrose gradients. The F.D.A. approved a gene therapy for hemophilia A for the first time. It’s called Roctavian and it’s only available for people who don’t have antibodies against AAV5, which is the viral vector used to deliver the gene therapy. The F.D.A. also approved a cellular therapy, called Lantidra, to treat a rare form of type 1 diabetes that affects roughly 3 out of 1,000 people with type 1 diabetes. The therapy works by replacing beta-cells with “fresh” cells taken from a, err…dead person.

Transcription factors are proteins that bind to DNA and control gene expression. At least, that’s what every textbook says. And it’s true, but only in an incomplete way. Because it turns out that at least half of them, in humans, also bind to RNA molecules. These protein:RNA duos seem to regulate gene expression in a way that we don’t really understand. And, at least in zebrafish, there are also lots of diseases that crop up when you mutate the bits of these proteins that bind to RNAs, including cancers and developmental disorders. I suspect this study will ignite a firestorm of research. Fortunately, there are many unanswered questions. How do transcription factors couple up with the correct RNA molecule? And how do they work together to control genes in the cell?

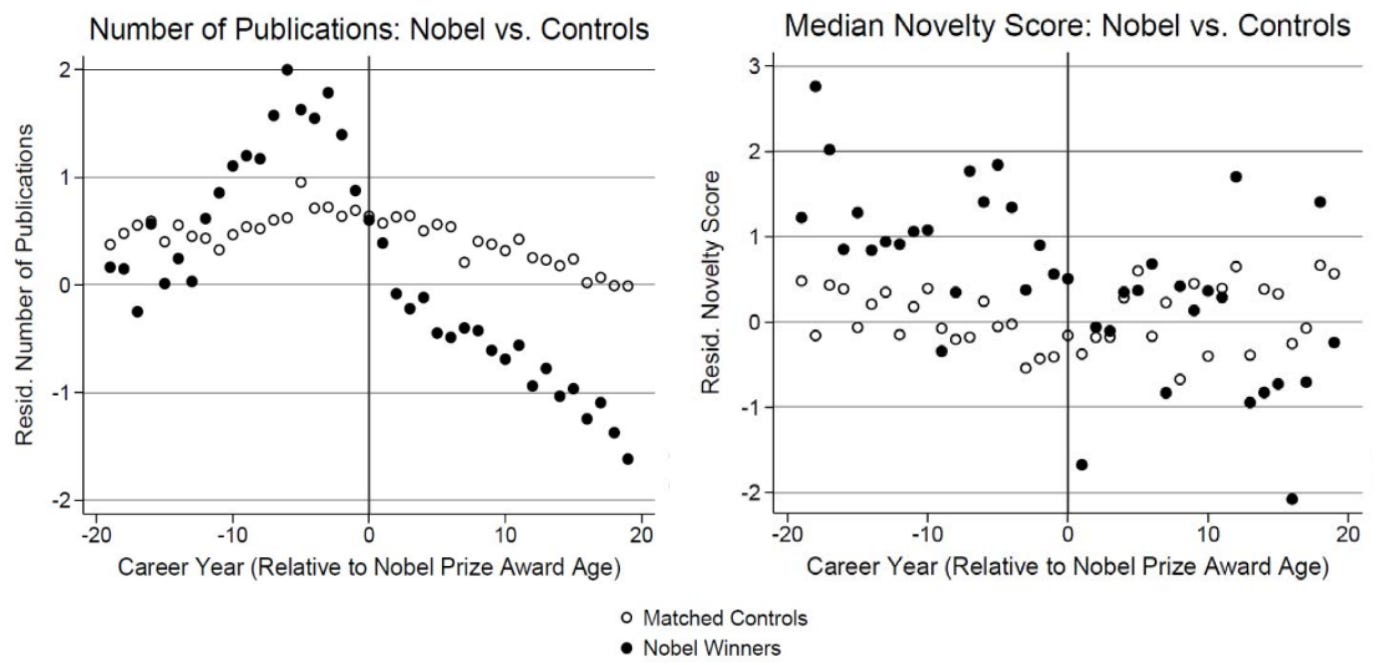

Winning a Nobel Prize reduces scientific output because the winner attends more events, talks to more journalists, and generally deals with more bureaucrats. From the Science article:

Researchers behind the study analyzed data on Nobel Prize winners in physiology and medicine between 1950 and 2010, charting how three factors changed after their awards: the number of papers they published; the impact of those papers, based on how often they were cited; and how novel their ideas were…

Before winning the prize, future Nobel laureates published more frequently than their colleagues who eventually won the Lasker Award, and they also published more-novel papers and garnered more citations. After winning a Nobel, however, the trend flipped: Nobel winners, on average, saw declines in productivity, novelty, and citations, dropping to even with the Lasker winners, or sometimes below them. In terms of raw numbers, future Nobel winners published about one study more per year than future Lasker winners in the 10 years leading up to the prize. In the 10 years after winning, however, the Lasker group published about one more study annually than did their Nobel laureate peers.Full study here.

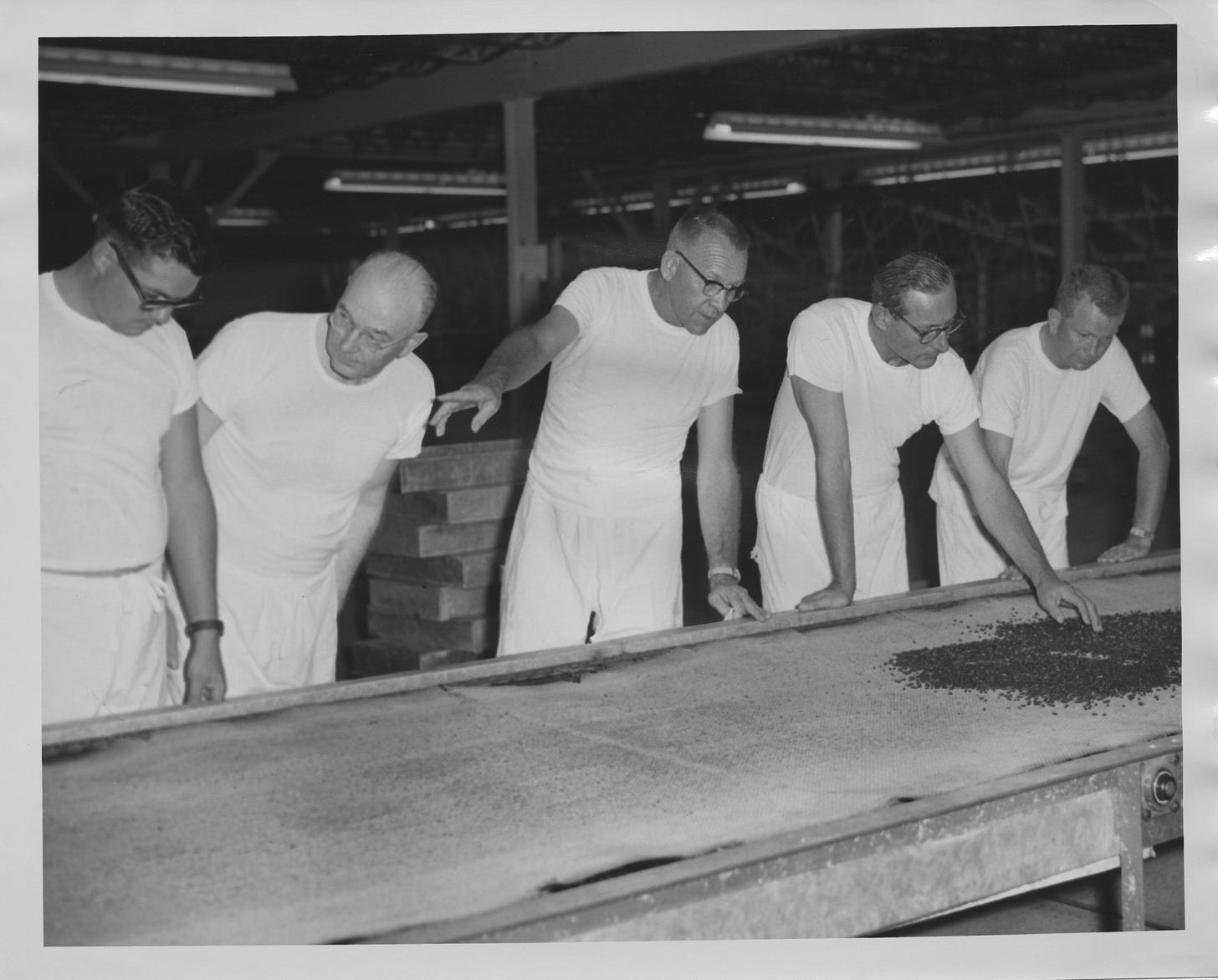

In the 1930s, screwworm flies caused “180,000 livestock deaths in under half the counties in Texas,” according to a U.S.D.A. history. This fly, endemic to the Americas, feasts on decaying flesh. They lay eggs inside the wounds of dying cows. In response, the U.S. government funded a massive effort: To sterilize millions of screwworms, initially with hospital x-ray machines, and air drop them over Florida, Texas, and elsewhere. The irradiated males would compete with healthy males for mates, it was thought, and gradually cause the population to fall. A pilot experiment was conducted on an island 40 miles north of Venezuela. “In 1954, screwworm flies were mass reared in Orlando, Florida, by USDA scientists and flown to Curaçao, where 400 sterile males per square mile were released by air. Effective eradication was achieved in 10 weeks,” the report says. Later, the U.S. government reared and sterilized some 50 million screwworms per week and swiftly eradicated the insects in Florida and in the southwest.

Now, I’m telling you this because using x-rays to sterilize insects is really inefficient. Some of the males leave the machines healthy-as-ever, and others become so unwell that they can’t seek out mates in the wild. A better option is to use CRISPR gene-editing, which is more precise and reliable. I’ve written about this before. But the basic gist is that you engineer female insects to express the Cas9 protein (one part of the CRISPR system), and engineer male insects to express guide RNAs. You then rear these insects together, in a massive warehouse. Their offspring have both the Cas9 protein and the guide RNA, which then cut two different genes: one for female survival and another for male fertility. When a gene-edited female lays her eggs, then, the female offspring never hatch, and the males hatch but can’t produce offspring of their own. (The male fertility gene is beta-tubulin, which helps sperm swim.)

A company, Agragene, has now started greenhouse tests with this technology (it’s licensed from Synvect, a spin-out from Omar Akbari’s lab at the University of California, San Diego). They are rearing CRISPR-sterilized spotted wing flies, which eat strawberries and other fruits, and aim to release them into the wild to knock down pest populations and protect crops. This is much the same intellectual spirit that helped the U.S.D.A. obliterate screwworms in the 1950s.Biotech company, eGenesis, is transplanting pig hearts into baby babboons. A spin-out from George Church’s lab at Harvard, the company has created pigs that carry about 70 edits in their genomes. Those edits eliminated proteins and viral genes that can cause immune reactions in people. The company plans to, one day, use organs from these gene-edited pigs to save babies born with congenital heart defects. For now, they are testing them in infant baboons — twelve in total. Two surgeries have been carried out so far, and “neither animal survived beyond a matter of days.” (Here is a good talk at the F.D.A. about how xenotransplants work and why they’d be so important. In 2019, about 4,000 Americans were waiting for a heart at any given time.) Meanwhile, David Bennett remains the only person to receive a pig heart transplant, and he died two months later from heart failure, not rejection. A recent study in Nature Medicine also did pig-to-human xenotransplants in two “brain-dead” people, monitored the organs for 66 hours, and saw no signs of “hyperacute rejection or zoonosis.”

Fractyl Health is making a “one-time gene therapy…to lower blood sugar and body weight using the same mechanism as semaglutide,” the weight loss drug. It’s ostensibly marketed for diabetes, but we all know where the real money’s at.

A complete, whole-brain connectome of the fruit fly has been published. All 130,000 neurons are annotated, along with 50 million connections between them. “For every neuron, one can now query its connectivity, size, neurotransmitter, labels, etc. but also analyze network graphs and find pathways between neurons,” writes Sven Dorkenwald, first-author of the study. The full connectome can be explored online. It’s even possible to digitally simulate the neural circuits that underlie eating or grooming, as a May preprint shows.

RNA export systems. Normally, RNA is confined to the cell in which it’s made. If we want to study RNA, or sequence it, then we need to kill the cells. No longer. A new paper from Michael Elowitz’s group at Caltech reports engineered RNA exporters that “efficiently and specifically package and secrete target RNA molecules from mammalian cells within protective nanoparticles.” This will open up many possibilities, including long-term studies of how transcription changes over time, in single cells, in response to cancer or a drug or anything else. These RNA exporters also work across many organisms and cell types, and they don’t interfere with gene expression or cell growth. This may prove to be the most important paper of the year.

A new method could build an entire E. coli genome — which has 3 million bases — in less than two months. The genomes are assembled from ‘megachunks’ of DNA, each stretching 500,000 bases, that are each put together in about 10 days. For context, it took two years for the same lab to synthesize and stitch together an E. coli genome just a few years ago.

Nearly all cellular compartments, in nature, are filled with liquid. Life is liquid. It is gooey, oozey stuff. And yet, the only rule in biology is that there are exceptions to every rule. A small number of microbes, we now know, also contain gas vesicles, which are hollow protein shells filled with air. These microbes use the empty vesicles for buoyancy; to float up-and-down in a lake, say, to maximize exposure to the sun for photosynthesis. In 2014, some clever engineers figured out how to express these gas vesicles in other types of cells and also showed that they produce contrast on ultrasound images. Gas vesicles can even be used to watch bacteria move through the body. And now, those same scientists have made miniature versions of these vesicles that measure just 60 nanometers across; roughly 1,700-times thinner than a piece of paper. These mini-gas vesicles still produce ultrasound contrast, but are now small enough to travel into tumors to deliver therapeutic payloads.

Eukaryotic cells (not humans!) naturally express RNA-guided endonucleases that, much like Cas9, use short snippets of RNA to ‘hunt down’ and cut DNA. These CRISPR systems, taken from various fungi and also from a mollusc, are widespread and can be reprogrammed to edit the human genome, all while carrying (perhaps!) a lower risk of immune responses. The proteins are called Fanzor, which is a cool name, and the paper is here.

Jiankui He, the CRISPR babies guy who spent three years in a Chinese prison and was released in April 2022, is back on the scene and tweeting about how he’s going to edit human embryos to protect them from Alzheimer’s disease. He does not immediately plan to implant the gene-edited embryos to cause a pregnancy, but reputable scientists, of course, have avoided engaging with the tweet like it’s the plague; just 133 likes after nearly 250,000 views.

A YouTuber, The Thought Emporium, is growing rat neurons in the laboratory. He says that, in a future video, he will use them to play the classic 1993 shooter game, DOOM. Are there other biology YouTubers that you enjoy watching?

Lots more CRISPR news, including dozens of new miniature gene-editing proteins. Two of these proteins are about 30% the size of Cas9, and thus much easier to package into viruses for gene therapy. Another paper recently reported an engineered Cas protein that is “up to 11.3-fold more potent than its parent protein…and one-third of the size of SpCas9.” And a third paper (BOOM!) reports Cas9 proteins that can penetrate into the central nervous system without being packaged into an adeno-associated virus, all while causing a lower immune response than a prior version of the same technology.

A great resource on biosecurity, written by Aron Lajko. There are many reasons why you should read Aron’s work, and then work on this problem. Here are just a few:

About 30,000 people know how to synthesize an influenza virus, at a cost of about $5,000.

The standards for screening possibly pathogenic DNA sequences are, to put it bluntly, a joke. Every DNA synthesis company basically does their own thing. “No US or international law requires companies that print DNA sequences to check what exactly they’re selling or who they're selling it to,” writes Kelsey Piper in Vox. Benchtop DNA synthesis machines will likely make it easier to create pathogens.

AI tools may not make it easier for someone with existing knowledge to create a pathogen, but they will lower barriers to entry.

Recent talk by Kevin Esvelt for the Foresight Institute.

“How to clone a plasmid really fast and have it work basically every time.” A blog by Olek Pisera, PhD student at UC Irvine. More scientists should write stuff like this. Let me know if it works for you!

milky eggs on lifespan extension. A long, speculative review of the evidence. Main takeaways: Rapamycin is possibly OK. Lots of fiber is good. Eat a healthy diet and avoid simple sugars. Exercise a lot. Use sunscreen.

A new method can mutate up to 15,000 bases of DNA in bacterial cells at rates 6,700-fold higher than normal. This is, in other words, an "evolution supercharger.” The tool was crafted with a virus, called GIL16. The authors took the genome from this virus and replaced its “bad” genes with a gene to be mutated. GIL16 also encodes a DNA polymerase that specifically recognizes, and replicates, only these genes. An AI tool, AlphaFold2, was used to make the viral DNA polymerase dramatically more error-prone. Now, when they put the viral DNA, along with the gene of interest, into a bacterium, the cells rapidly mutate just the added DNA, while leaving the normal genome alone. In about two weeks of work, the researchers evolved cells that can eat methanol 7.4-fold faster than normal. This isn’t the first tool to super-charge evolution, but it is the first to do it in bacteria.

Tony Kulesa wrote a blog about Y Combinator and why it has been uniquely successful. It’s a really great piece with lots of insights. Can we emulate this model for high-capital industries, like biotechnology? Or for creative pursuits, such as writing?

A minimal cell, with just 473 genes, evolves just as fast as a cell with a normal-sized genome. In other words, evolution is not dependent on ‘throw-away’ genes. It persists at much the same rate, even when every gene is considered essential for survival. This claim comes from a new study in Nature. A few years ago, scientists made a “minimal” version of Mycoplasma mycoides, a parasite that infects goats and pigs. They eliminated hundreds of genes from this organism, which already had the smallest genome of any species that can be independently grown in a laboratory. This minimal cell, first reported in 2016, was about half as fit as a normal M. mycoides cell. They grow slowly and generally look sluggish. But now, this new paper shows that the minimal cells have regained normal fitness levels after 2,000 generations. Each nucleotide in the cells’ genome was hit with a mutation about 250 times during those 2,000 generations. That’s quite a lot. The evolved, minimal cells also swelled about 85% in diameter, which corresponds to a tenfold increase in volume. As the surface area-to-volume ratio shrinks, cells are able to do more stuff for less energy. But a bigger size also means that biochemical reactions become more limited by diffusion. This is a trade-off, of course; a bigger size is generally good when you have ready access to nutrients, such as in a laboratory.

Memes.

What an awesome roundup. Thank you!

+1 for Primordium, their turnaround time is remarkably fast.